We learn that, just as Henry told me privately, they have crowned a boy king in Dublin and declared that he is Edward of Warwick and the true king of England, Ireland, and France.

My Lady stops speaking to me; she can hardly bear to be in the same room as me. I may be her daughter-in-law, but she can only see me as the daughter of the house that has raised up this threat, whose aunt Margaret is pouring money and weapons into Ireland, whose aunt Elizabeth provided the commander, whose mother is masterminding the plot from behind the high walls of Bermondsey Abbey. She will not speak to me, she cannot bear to look at me. Only once in this difficult time she stops me as I walk past her rooms with my sisters and my cousin on my way to the stables for our horses. She puts her hand on my arm as I walk by, and I drop a curtsey to her and wait for what she has to say.

“You know, don’t you?” she demands. “You know where he is. You know he is alive.”

I cannot answer her white-faced fears. “I don’t know what you mean.”

“You know very well what I mean!” she spits furiously. “You know he’s alive. You know where he is. You know what they plan for him!”

“Shall I call your ladies?” I ask her. The hand that grips my arm is shaking, I really fear that she is going to fall down in a fit. Her gaze, always intense, is fixed on my face, as if she would force her way into my mind. “My Lady, shall I call your ladies and help you to your rooms?”

“You’ve fooled my son, but you don’t fool me!” she hisses. “And you will see that I command here, and that everyone who has treasonous thoughts, high or low, will be punished. Treasonous heads will be cut from their corrupt bodies. High and low, nobody will be spared at Judgment Day. The sheep will be parted from the goats, and the unclean will go down to hell.”

Cecily is staring at her godmother, quite horrified. She steps forwards, and then she shrinks back from the woman’s anguished dark glare.

“Ah,” I say coldly. “I misunderstood you. You are speaking of this pretender in Ireland? And whether you command here, or whether you have to flee from here in terror, we will know very soon, I am sure.”

At the very word “flee,” she tightens her grip and sways on her feet. “Are you my enemy? Tell me, let us have honesty between us. Are you my enemy? Are you the enemy of my beloved son?”

“I am your daughter-in-law and the mother of your grandchild,” I say as quietly as her. “This is what you wanted and this is what you have. Whether I love him or hate him, that is between ourselves. Whether I love you or hate you, that was your doing too. And I think you know the answer.”

She flings my hand away as if my touch is repellent. “I will see you destroyed the day that you raise him up against us,” she warns me.

“Raise him up?” I repeat furiously. “Raise him up? It sounds like you think we would raise the dead! What can you mean? Who do you fear, My Lady?”

She gives a racking sob and she gulps down an answer. I sweep her the smallest curtsey, and I go on my way to the stables. I duck into my horse’s stall and slam the stable door behind me to rest my head against his warm neck. I take a shuddering breath and realize that she has told me that they believe my brother is alive.

KENILWORTH CASTLE, WARWICKSHIRE, JUNE 1487

I hardly see Henry, who is closeted with his uncle Jasper and John de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, forever sending messages to the lords, trying their loyalty, asking them to come to him. Many, very many, take their time in replying. Nobody wants to declare as a rebel too soon; but equally, nobody wants to be on the losing side with a new king. Everyone remembers that Richard looked unbeatable when he rode out from Leicester, and yet a small paid army confronted him, and a traitor cut him down. The lords who promised their support to that king, and yet sat on their horses and watched for the outcome on the day of battle, may decide to be bystanders once again and intervene only on the winning side.

Henry comes to my rooms only once during this anxious time, with a letter in his hand. “I will tell you this myself so that you don’t hear it from a York traitor,” he says unpleasantly.

I rise to my feet and my ladies melt away from my husband’s temper. They have learned, we have all learned, to keep out of the way of the Tudors, mother and son, when they are pale with fear. “Your Grace?” I say steadily.

“The King of France has chosen this moment, this very moment, to release your brother Thomas Grey.”

“Thomas!”

“He writes that he will come to support me,” Henry says bitterly. “You know, I don’t think we’ll risk that. When Thomas was last supporting me on the road to Bosworth, he changed his mind and turned his coat before we even left France. Who knows what he would have done on the battlefield? But they’re releasing him now. Just in time for another battle. What d’you think I should do?”

I hold on to the back of a chair so that my hands don’t tremble. “If he gives you his word . . .” I begin.

He laughs at me. “His word!” he says scathingly. “The York word! Would that be as binding as your mother’s word of honor? Or your cousin John’s? Your marriage vows?”

I start to stammer a reply but he puts up his hand for silence. “I’ll hold him in the Tower. I don’t want his help, and I don’t trust him free. I don’t want him talking to his mother, and I don’t want him seeing you.”

“He could . . .”

“No, he couldn’t.”

I take a breath. “May I at least write and tell my mother that her son, my half brother, is coming home?”

He laughs, a jeering unconvincing laugh. “D’you think she won’t know already? D’you think she has not paid his ransom and commanded his return?”

I write to my mother at Bermondsey Abbey. I leave the letter unsealed for I know that Henry or his mother or his spies will open it and read it anyway.

My dear Lady Mother,

I greet you well.

I write to tell you that your son Thomas Grey has been released from France and has offered his service to the king, who has decided, in his wisdom, to hold my half brother in safekeeping in the Tower of London for the time being.

I am in good health, as is your grandson.

Elizabeth

P.S. Arthur is crawling everywhere and pulling himself up on chairs so that he can stand. He’s very strong and proud of himself, but he can’t walk yet.

Henry says he must leave me and the ladies of the court, our son Arthur with his own yeomen of the guard in his nursery, and his frantically anxious mother behind the strong walls of Kenilworth Castle, muster his army, and march out. I walk with him to the great entrance gate of the castle, where his army is drawn up in battle array, behind their two great commanders: his uncle Jasper Tudor and his most reliable friend and ally, the Earl of Oxford. Henry looks tall and powerful in his armor, reminding me of my father, who always rode out to battle in the absolute certainty that he would win.

“If it goes against us, you should withdraw to London,” Henry says tightly. I can hear the fear in his voice. “Get yourself into sanctuary. Whoever they put on the throne will be your kinsman. They won’t hurt you. But guard our son. He’ll be half a Tudor. And please . . .” He breaks off. “Be merciful to my mother, see that they spare her.”

“I’m never going into sanctuary again,” I say flatly. “I’m not raising my son inside four dark rooms.”

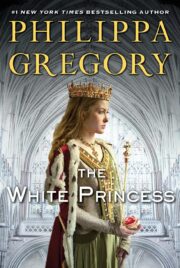

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.