“Spying,” Thomas Grey tells me. “Morton and My Lady the King’s Mother together run the greatest spy network that the world has ever seen, and not a man moves in and out of England but their son and protégé know of it.”

My half brother is seated with me in my presence chamber, and the music for dancing covers our words as my ladies practice new steps in one corner of the room and we talk in another. I hold up my sewing to cover my face so that no one can see my lips. I am so pleased to see him after so long that I cannot keep myself from beaming.

“Have you seen our Lady Mother?” I ask.

He nods.

“Is she well? Does she know I am to be crowned?”

“She’s well, quite happy at the abbey. She sent you her love and best wishes for your coronation.”

“I can’t get him to release her to court,” I admit. “But he knows he can’t hold her there forever. He has no cause.”

“Yes but he does have cause,” my half brother says with a wry smile. “He knows that she sent money to Francis Lovell and John de la Pole. He knows that she has united all of the Yorkists who plot against him. Under Henry’s nose, under your nose, she was running a spy network of her own, from Scotland to Flanders. He knows that she has been linking all of them, in turn, to Duchess Margaret in Flanders. But what drives him quite mad is that he can’t say that out loud. He can’t accuse her, because to do so would be to admit that there was a plot against him, inspired by our mother, funded by your aunt, and assisted by your grandmother, Duchess Cecily. He can’t admit to England that the surviving House of York is completely united against him. By exposing the conspiracy, he shows the threat they are. It looks far too much like a conspiracy of women in favor of a child of their household. It is overwhelming evidence for the one thing that Henry wants to deny.”

“What is that?” I ask.

Thomas leans his chin on his hand so his fingers cover his mouth. No one can read his lips as he whispers, “It looks as though those women are working together for a York prince.”

“But Henry says that since no York prince came to England, ready for the victory, he cannot exist.”

“Such a boy would be a precious boy,” Thomas objects. “You wouldn’t bring him to England until the victory was won and the coast secure.”

“A precious boy?” I echo. “You mean a pretend prince, a false token. A counterfeit.”

He smiles at me. Thomas has been under arrest in one place or another for two long years: in France since before the battle of Bosworth, and more recently in the Tower of London. He’s not going to say anything that will put him back behind bars again.

“A pretender. Of course, that is all that he could possibly be.”

Henry stays in London only long enough to assure everyone that his victory over the rebels was total, that he was never in any danger, and that the crowned king that they paraded in Dublin is now a frightened boy in prison; then he takes his most trusted lords and goes north again, to one great house after another where he holds inquiries and learns which lords failed to secure the roads, who whispered to someone else that there was no need to support the king, those who looked the other way while the rebel army stormed by, and those who saddled up, sharpened their swords, and treasonously went out to join them. Relentlessly, dealing in details and whispers, gatepost gossip and alehouse insults, Henry tracks down every single man whose loyalty wavered when the cry went up for York. He is determined that those men who joined the rebels should be punished, some put to death as traitors but most fined to the point of ruin, and the profit paid to the royal treasury. He ventures as far north as Newcastle, deep into the York heartlands, and sends ambassadors to the court of James III of Scotland with proposals for a peace treaty and for marriages to make the treaties hold firm. Then he turns and rides home to London, a conquering hero, leaving the North reeling with death and debt.

He summons the boy Lambert Simnel to his presence chamber and commands the attendance of his whole court: My Lady the King’s Mother, an eager spectator of her son’s doings; myself with my ladies headed by my two sisters, my cousin Maggie at my side; my aunt Katherine, smilingly accompanying her victorious husband, Jasper Tudor; all the faithful lords and those who have managed to pass as faithful. The double doors slam open, and the yeomen guard ground their pikes with a bang and shout the name, “John Lambert Simnel!” and everyone turns to see a skinny boy, frozen in the doorway until someone pushes him inwards and he takes a few steps into the room and then sinks on his knees to the king.

My first thought is that he does indeed look very like my brother looked, when I last saw him. This is a blond, pretty boy of about ten years old, and when my mother and I smuggled my brother out of sanctuary that dark evening, he was as bright and as slender as this. Now, if he is alive somewhere, he would be about fourteen, he would be growing into a young man. This child could never have passed for him.

“Does he remind you of anybody?” The king takes my hand and leads me from my chair beside his to walk down the long room to where the boy is kneeling, his head bowed, the nape of his neck exposed, as if he expects to be beheaded here and now. Everyone is silent. There are about a hundred people in the privy chamber and everyone turns to look at the boy as Henry approaches him, and the child droops lower and his ears burn.

“Anyone think he looks familiar?” Henry’s hard gaze rakes my family, my sisters with their heads down as if they are guilty, my cousin Maggie with her eyes on the little boy who looks so like her brother, my half brother Thomas who is gazing around indifferently, determined that no one shall see him flinch.

“No,” I say shortly. He is slight like my brother Richard and has cropped blond hair like his. I can’t see his face but I caught a glimpse of hazel eyes like my brother’s, and at the back of his head there are a few childish curls on the nape of the neck, just like Richard’s. When he used to sit at my mother’s feet, she would twist his curls around her fingers as if they were bright golden rings, and she would read to him until he was sleepy and ready for bed. The sight of the little boy, on his knees, makes me think once more of my brother Richard, and of the page that we sent into the Tower to take his place, of my missing brother Prince Edward, and of my cousin Edward of Warwick—Maggie’s brother—in the Tower alone. It is as if there is a succession of boys, York boys, all bright, all charming, all filled with promise; but nobody can be sure where they are tonight, or even if they are alive or dead, or if they are unreal, flights of fancy and pretenders like this one.

“Does he not remind you of your cousin Edward of Warwick?” Henry asks me, speaking clearly so that the whole court can hear.

“No, not at all.”

“Would you ever have mistaken him for your dead brother Richard?”

“No.”

He turns from me, now that this masque has been played out and everyone can say that the boy knelt before us and I looked at him and denied him. “So anyone who thought that he was a son of York was either deceived or a deceiver,” Henry rules. “Either a fool or a liar.”

He waits for everyone to understand that John de la Pole, Francis Lovell, and my own mother were fools and liars, and then he goes on: “So, boy, you are not who you said you were. My wife, a princess of York, does not recognize you. She would say if you were her kinsman as you claim. But she says you are not. So who are you?”

For a moment I think the child is so afraid that he has lost the power of speech. But then, keeping his head down and his eyes on the ground, he whispers: “John Lambert Simnel, if it please Your Grace. Sorry,” he adds awkwardly.

“John Lambert Simnel.” Henry rolls the name around his tongue like a bullying schoolmaster. “John. Lambert. Simnel. And how ever have you got from your nursery, John, to here? For it has been a long journey for you, and a costly and time-consuming trouble for me.”

“I know, Sire. I’m very sorry, Sire,” the child says.

Someone smiles in sympathy at the little treble voice, and then catches Henry’s furious look and glances away. I see Maggie’s face is white and strained and Anne is shaking and slips her hand into Cecily’s arm.

“Did you take the crown on your head though you knew you had no right to it?”

“Yes, Sire.”

“You took it under a false name. It was put on your head but you knew your lowborn head did not deserve it.”

“Yes, Sire.”

“The boy whose name you took, Edward of Warwick, is loyal to me, recognizing me as his king. As does everyone in England.”

The child has lost his voice; only I am close enough to hear a little sob.

“What d’you say?” Henry shouts at him.

“Yes, Sire,” the child quavers.

“So it meant nothing. You are not a crowned king?”

Obviously, the child is not a crowned king. He is a lost little boy in a dangerous world. I nip my lower lip to stop myself from crying. I step forwards and I gently put my hand in Henry’s arm. But nothing will restrain him.

“You took the holy oil on your breast but you are not a king, nor did you have any right to the oil, the sacred oil.”

“Sorry,” comes a little gulp from the child.

“And then you marched into my country, at the head of an army of paid men and wicked rebels, and were completely, utterly defeated by the power of my army and the will of God!”

At the mention of God, My Lady the King’s Mother steps forwards a little, as if she too wants to scold the child. But he stays kneeling, his head sinks lower, he almost has his forehead on the rushes on the floor. He has nothing to say to either power or God.

“What shall I do with you?” Henry asks rhetorically. At the startled look on the faces of the court, I realize that they have suddenly understood, like me, that this is a hanging matter. It is a matter for hanging, drawing, and quartering. If Henry hands this child over to the judge, then he will be hanged by his neck until he is faint with pain, then the executioner will cut him down, slide a knife from his little genitals to his breastbone, pull out his heart, his lungs, and his belly, set light to them before his goggling eyes, and then cut off his legs and his arms, one by one.

I press Henry’s arm. “Please,” I whisper. “Mercy.”

I meet Maggie’s aghast gaze and see that she too has realized that Henry may take this tableau through to a deathly conclusion. Unless we play another scene altogether. Maggie knows that I can perform one great piece of theater and that I may have to do this. As the wife of the king, I can kneel to him publicly and ask for clemency for a criminal. Maggie will come forwards and take off my hood, and my hair will tumble down around my shoulders, and then she will kneel, all my ladies will kneel behind me.

We in the House of York have never done such a thing, as my father liked to deal out punishment or mercy on his own account, having no time for the theater of cruelty. We in the House of York never had to intercede for a little boy against a vindictive king. They did it in the House of Lancaster: Margaret of Anjou on her knees for misled commoners before her sainted husband. It is a royal tradition, it is a recognized ceremony. I may have to do it to save this little boy from unbearable pain. “Henry,” I whisper. “Do you want me to kneel for him?”

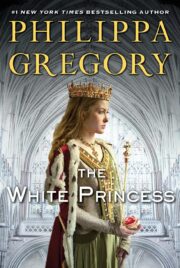

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.