I take him immediately to the nursery at Eltham Palace to show him how much Arthur has grown. He can stand up now and walk alongside a chair or a stool. His greatest pleasure is to hold my fingers and take wavering steps across the room, turn around with his little feet pigeon-toed, and forge back again. He beams when he sees me and reaches out for me. He is starting to speak, singing like a little bird, though he has no words yet, but he says “Ma,” which I take to mean me, and “Boh,” which means anything that pleases him. But he giggles when I tickle him and drops anything that he is given in the hope that someone will pick it up and return it to him, so that he can drop it again. His greatest joy is when Bridget gives him a ball to drop, and flies after it as if they were playing tennis and she has to recover it before it bounces too often; it makes him gurgle and crow to see her run. “Is he not the most beautiful boy you have ever seen?” I ask Uncle Edward, and am rewarded by his toothless beam.

“And the boy you went to see?” I ask quietly, taking Arthur against my shoulder and gently patting his back. He is heavy on my shoulder and warm against my cheek. I have a sudden fierce desire that nothing shall ever threaten his peace or his safety. “Henry told me that he sent you to look at a boy in Portugal? I have heard nothing of him since you left.”

“Then the king will tell you that I saw a page boy in the service of Sir Edward Brampton,” my uncle says, his lisp endearing. “Some mischief-maker thought that he looked like my poor lost nephew Richard. People will make trouble over nothing. Alas, that they have nothing better to do.”

“And does he look like him?” I press.

Edward shakes his head. “No, not particularly.”

I glance around. There is no one near but the baby’s wet nurse and she has no interest in anything but eating enormous meals and drinking ale. “My lord uncle, are you sure? Can you speak to my Lady Mother about him?”

“I won’t speak to her of this lad because it would distress her,” he says firmly. “It was a boy who looked nothing like your brother, her son. I am sure of it.”

“And Edward Brampton?” I persist.

“Sir Edward is to come on a visit to England as soon as he can leave his business in Portugal,” he says. “He is letting his handsome page go out of his service. He does not want to cause any embarrassment to us or to the king with such a forward boy.”

There is more here than I can understand. “If the boy is nothing, a braggart, then how could such a nothing make such a loud noise in Lisbon that we can hear him in London? If he is a nothing, why did you go all the way to Portugal to see him? It’s nowhere near Granada. And why is Sir Edward coming to England? To meet with the king? Why would he be so honored, when he was known to be loyal to York and he loved my father? And why is he dismissing his page if the boy is a nobody?”

“I think the king would prefer it,” Edward says lightly.

I look at him for a moment. “There is something here that I don’t understand,” I say. “There is a secret here.”

My uncle pats my hand as I hold the baby’s warm body to my heart. “You know, there are always secrets everywhere; but it is better sometimes that you don’t know what they are. Don’t trouble yourself, Your Grace,” he says. “This new world is filled with mysteries. The things they told me in Portugal!”

“Did they speak of a boy returned from the dead?” I challenge him. “Did they speak of a boy who was hidden from unknown killers, smuggled abroad, and waiting for his time?”

He does not flinch. “They did. But I reminded them that the King of England has no interest in miracles.”

There is a little silence. “At least the king trusts you,” I say as I hand Arthur back to his wet nurse and watch him settle on her broad lap. “At least he is sure of you. Perhaps you can speak to him of my Lady Mother and she can come back to court. If there is no boy, then he has nothing to fear.”

“He’s not naturally a very trusting man,” my uncle observes with a smile. “I was followed all the way to Lisbon and my hooded companion noted everyone that I met. Another man followed me home again too, to make sure that I did not call on your aunt in Flanders on my way.”

“Henry spied on you? His own messenger? His spy? He spied on his spy?”

He nods. “And there will be a woman in your household who tells him what you say in your most private moments. Your own private confessor is bound to report to his Father in God, the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Morton. John Morton is the greatest friend of My Lady the King’s Mother. They plotted together against King Richard, together they destroyed the Duke of Buckingham. They meet every day and he tells her everything. Don’t ever dream that the king trusts any of us. Don’t ever think that you’re not watched. You are watched all the time. We all are.”

“But we’re doing nothing!” I exclaim. I lower my voice. “Aren’t we, Uncle? We are doing nothing?”

He pats my hand. “We’re doing nothing,” he assures me.

WINDSOR CASTLE, SUMMER 1488

But though Henry may be right and James is loyal in his heart, he can’t persuade his countrymen to support England. His country, his lords, even his heir are all against Tudor England, whatever the opinions of the king, and it is the country that wins. They turn against him rather than stomach an alliance with the Tudor arriviste, and James has to defend his friendship with England and even his throne. I receive a hastily scribbled note from my mother, but I don’t understand what she means:

So you see, I am not riding up the Great North Road.

I know that Henry will have seen this, almost as soon as it was written, so I take it at once to him to demonstrate my loyalty; but as I enter the royal privy chamber I stop, for there is a man with him that I think I know, though I cannot put a name to his darkly tanned face. Then as he turns towards me I think I had better forget everything I have ever known about him. This is Sir Edward Brampton, my father’s godson, the man that my uncle saw at the court in Portugal with the forward page boy. He turns and bows low to me, his smile quietly confident.

“You know each other?” my husband says flatly, watching my face.

I shake my head. “I am so sorry . . . you are?”

“I am Sir Edward Brampton,” he says pleasantly. “And I saw you once when you were a little princess, too young to remember an unimportant old courtier like me.”

I nod and turn my entire attention to Henry, as if I have no interest in Sir Edward at all. “I wanted to tell you that I have a note from Bermondsey Abbey.”

He takes it from my hand and reads it in silence. “Ah. She must know that James is dead.”

“Is that what she means? She writes only that she won’t be riding up the Great North Road. How did the king die? How could such a thing happen?”

“In battle,” Henry says shortly. “His country supported his son against him. It seems that some of us cannot even trust blood kin. You cannot be sure of your own heir, never mind another.”

Carefully I do not look towards Sir Edward. “I am sorry if this causes us trouble,” I say evenly.

Henry nods. “At any rate, we have a new friend in Sir Edward.”

I smile slightly, Sir Edward bows.

“Sir Edward is to come home to England next year,” Henry says. “He was a loyal servant of your father’s and now he is going to serve me.”

Sir Edward looks cheerful at this prospect and bows again.

“So when you reply to your mother, you can tell her that you have seen her old friend,” Henry suggests.

I nod and go towards the door. “And tell her that Sir Edward had a forward page boy, who made much of himself, but that he has now left his service and gone to work for a silk merchant. Nobody knows where he is now. He may have gone trading to Afric, perhaps to China, no one knows.”

“I’ll tell her that, if you wish,” I say.

“She’ll know who I mean,” Henry smiles. “Tell her that the page boy was an insolent little lad who liked to dress in borrowed silks but now he has a new master—a silk merchant as it happens, so he will be well suited in his work, and the boy has gone with him, and is quite disappeared.”

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, CHRISTMAS 1488

“The king is allowing him a schoolmaster and some books,” she says. “And he has a lute. He’s playing music and composing songs, he sang one to me.”

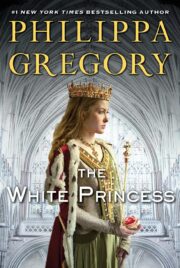

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.