Henry comes to my room every night after dinner and sits by the fire and talks about the day; sometimes he lies with me, sometimes he sleeps with me till morning. We are comfortable together, even affectionate. When the servants come and turn down the bed and take off my robe, he puts them to one side with his hand. “Leave us,” he says, and when they go out and close the door, he slips my robe from my shoulders himself. He puts a kiss on my naked shoulder and helps me into the high bed. Still dressed, he lies on the bed beside me and strokes my hair away from my face. “You’re very beautiful,” he says. “And this is our third Christmas together. I feel like a man well married, long married and to a beautiful wife.”

I lie still and let him pull the ribbon from the end of my plait and run his fingers through the sleek golden hanks of hair. “And you always smell so delicious,” he says quietly.

He gets up from the bed and unties the belt on his robe, takes it off, and lays it carefully on a chair. He is the sort of man who always keeps his things tidy. Then he lifts the bedding and slides in beside me. He is desirous and I am glad of it, for I want another child. Of course, we need another son to make the succession secure; but on my own account, I want that wonderful feeling of a baby in my belly and the sense of growing life within. So I smile at him and lift the hem of my robe and help him to move on me. I reach for him and feel the warm strength of his flesh. He is quick and gentle, shuddering with his own easy pleasure; but I feel nothing more than warmth and willingness. I don’t expect more, I am glad to at least feel willing, and grateful to him that he is gentle. He lies on me for a little while, his face buried in my hair, his lips at my neck, then he lifts himself away from me and says, surprisingly: “But it’s not like love, is it?”

“What?” I am shocked that he should say such a bald truth.

“It’s not like love,” he says. “There was a girl when I was a young man, in exile in Brittany, and she would creep out from her father’s house, risking everything to be with me. I’d be hiding in the barn, I used to burn up to see her. And when I touched her she would shiver, and when I kissed her she would melt, and once she held me and wrapped her arms and legs around me and cried out in her pleasure. She could not stop and I felt her sobs shake her whole body with joy.”

“Where is she now?” I ask. Despite my indifference to him I find I am curious about her, and irritated at the thought of her.

“Still there,” he says. “She had a child by me. Her family got her married off to a farmer. She’ll probably be a fat little farmer’s wife by now with three children.” He laughs. “One of them a redhead. What d’you think? Henri?”

“But no one calls you a whore,” I observe.

His head turns at that and he laughs out loud, as if I have said something extraordinary and funny. “Ah, dear heart, no. Nobody calls me a whore for I am King of England and a man. Whatever else you might like to change in the world, a York king on the throne, the battle reversed, Richard arising from the grave, you cannot hope to change the way that the world sees women. Any woman who feels desire and acts on it will always be called a whore. That will never change. Your reputation was ruined by your folly with Richard, for all that you thought it was love, your first love. You have only regained your reputation by a loveless marriage. You have gained a name but lost pleasure.”

At his casual naming of the man I love, I pull the covers up to my chin and gather my hair and plait it again. He does not stop me, but watches me in silence. Irritated, I realize that he is going to stay the night.

“Would you like your mother to come to court for Christmas?” he asks casually, turning to blow out the candle beside the bed. The room is lit only by the dying fire, his shoulder bronzed by the light of the embers. If we were lovers this would be my favorite time of the day.

“May I?” I almost stammer, I am so surprised.

“I don’t see why not,” he says casually. “If you would like her here.”

“I would like it above anything else,” I say. “I would like it very much. I would be so happy to have her with me again, and for Christmas, and my sisters, especially my little sisters . . . they’ll be so happy.” Impulsively I lean over and kiss his shoulder.

At once, he turns and catches my face and takes the kiss on his mouth. Gently, he kisses me again, and then again, and my distress at his mentioning Richard, and my jealousy of the girl he once loved, somehow prompt me to take his mouth against mine, and put my arms around his neck, then I feel his weight come on me and his body press against the length of me, as my lips open and I taste him and my eyes close as he holds me, and feel him gently, sweetly enter me again, and for the first time ever between the two of us, it does feel a little like love.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, SPRING 1489

“He didn’t have to go,” I say, lighting a candle for him on the altar of the chapel.

My mother smiles, though I know that she misses him. “Oh, he did,” she says. “He was never a man who could stay quietly at home.”

“You will have to go quietly to your home,” I point out. “The feast of Christmas is over and Henry says you have to go back to the abbey.”

She turns towards the door and pulls the hood forwards over her silvery hair. “I don’t mind, as long as you and the girls are well, and I see that you are happy and at peace in yourself.”

I walk beside her and she takes my hand. “And you? Are you coming to love him, as I hoped you would do?” she says.

“It’s odd,” I confess. “I don’t find him heroic, I don’t think he is the most marvelous man in the world. I know he’s not very brave, he’s often bad-tempered. I don’t love him as I did Richard . . .”

“There are many sorts of love,” she counsels me. “And when you love a man who is less than you dreamed, you have to make allowances for the difference between a real man and a dream. Sometimes you have to forgive him. Perhaps you even have to forgive him often. But forgiveness often comes with love.”

In April, when the birds are singing in the fields south of the river, I tell Henry that I will not ride out hawking with him. He is mounting up in the stable yard and my horse, that has been kept inside for days, is curvetting and dancing on the spot, held tightly with his reins by a groom.

“He’s just fresh,” Henry says, looking from the eager gelding to me. “You can manage him, surely? It’s not like you to miss a day’s hawking. As soon as you’re on him he’ll be all right.”

I shake my head.

“Have another horse,” Henry suggests. I smile at his determination that I should ride with him. “Uncle Jasper will let you have his. He’s steady as a rock.”

“Not today,” I persist.

“Are you not well?” He throws his reins to his groom and jumps down to come to my side. “You look a little pale. Are you well, my love?”

At that endearment, I lean towards him and his arm comes around my waist. I turn my head so my lips are at his ear. “I have just been sick,” I whisper.

“But you’re not hot?” He flinches a little. The terror of the sweating sickness that came with his army is still a strong one. “Tell me you’re not hot!”

“It’s not the sweat,” I assure him. “And it’s not a fever. It’s not something I ate, nor unripe fruit.” I smile at him, but still he does not understand. “I was sick this morning, and yesterday morning, and I expect to be sick tomorrow too.”

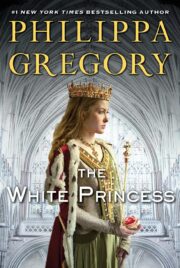

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.