He looks at me with dawning hope. “Elizabeth?”

I nod. “I’m with child.”

His arm tightens around my waist. “Oh, my darling. Oh, my sweetheart. Oh, this is the best news!”

In front of the whole court he kisses me warmly on the mouth and when he looks up, everyone must surely know what I have told him, for his face is radiant.

“The queen is not riding with us!” he shouts, as if it is the best news in the world.

I pinch his arm. “It’s too soon to tell anyone yet,” I caution him.

“Oh, of course, of course,” he says. He kisses my mouth and my hand. Everyone is looking with puzzled smiles at his joy. One or two nudge each other, guessing at once. “The queen is going to rest today!” he bellows. “There’s no need for concern. She is well. But she is going to rest. She is not going to ride. I don’t want her to ride. She is a little unwell.”

This confirms it; even the slowest young man whispers with his neighbor. Everyone guesses at once why Henry has me held tightly to his side and why he is beaming.

“You go and rest.” He turns to me, oblivious to the knowing smiles of his court. “I want you to make sure that you rest.”

“Yes,” I say, near to laughter myself. “I understand that. I think everyone understands that.”

He grins, sheepish as a shy boy. “I can’t hide how happy I am. Look, I’ll catch you the sweetest pheasant for your dinner.” He swings himself into the saddle. “The queen is unwell,” he tells the groom holding my mount. “You had better exercise her horse yourself. Today, and every day. I don’t know when she’ll be well enough to ride again.”

The groom bows to his knees. “I will, Your Grace,” he says. He turns to me: “I’ll keep him quiet for you so you can just walk out on him when you have a mind to it.”

“The queen is unwell,” Henry says to his companions, who are mounting up and beaming at him. “I shan’t say more.” He is grinning from ear to ear, like a boy. “I don’t say more. There’s no more to say.” He stands in his stirrups and raises his cap from his head and waves it in the air. “God save the queen!”

“God save the queen!” everyone shouts back at him and smiles at me, and I laugh up at Henry. “Very discreet,” I say to him. “Very courtly, very reticent, most discreet.”

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, AUTUMN 1489

“And I shall send for my mother to be with me,” I say.

At once her gaze sharpens. “Have you asked Henry?”

“Yes,” I lie to her face.

“And he has agreed?”

Clearly, she does not believe me for a moment.

“Yes,” I say. “Why would he not? My mother has chosen to live in retirement, a life of prayer and contemplation. She has always been a thoughtful and devout woman.” I look at the fixed expression on My Lady’s face—she has always prized herself as being formidably holy. “Everyone knows my mother has longed for the religious life,” I claim, feeling the lie grow more and more ambitious, and feeling myself tremble with the desire to giggle. “But I am sure she will consent to return to the world to stay with me when I am in confinement.”

Then, it is just a question of getting to Henry before his mother does so. I go to his rooms and though the door is shut to his presence chamber, I nod to the guard to let me in.

Henry is seated at a table in the center of the room with his most trusted advisors around him. He looks up as I come in and I see that he is scowling with worry.

“I’m sorry.” I hesitate in the doorway. “I didn’t realize . . .”

They all rise and bow and Henry comes quickly to my side and takes my hand. “It can wait,” he says. “Of course it can wait. Are you well? Nothing wrong?”

“Nothing wrong. I wanted to ask you a favor.”

“You know I can refuse you nothing,” he says. “What would you like? To bathe in pearls?”

“Just if my mother could be with me when I go into confinement.” As I say the words I see the shadow cross his face. “She was such a comfort to me last time, Henry, and she is so experienced, she has had so many children, and I need her.”

He hesitates. “She’s my mother,” I insist, my voice catching a little. “And it’s her grandchild.”

He thinks for a moment. “Do you have any idea what we are talking about here? Right now?”

I look past his shoulder at the grave-faced men, his uncle Jasper looking gloomily at a map. I shake my head.

“We keep getting reports from all over the country of little incidents of trouble. People planning to overthrow us, people plotting my death. In Northumberland a mob attacked the Earl of Northumberland, as he was collecting taxes for me. Not just a bit of rough play—d’you know, they pulled him off his horse and killed him?”

I gasp. “Henry Percy?”

He nods. “In Abingdon there’s a highly regarded abbot plotting against us.”

“Who?” I ask.

His face darkens. “It doesn’t matter who. In the northeast, Sir Robert Chamberlain and his sons were captured trying to set sail for your aunt in Flanders from the port of Hartlepool. Half a dozen little incidents, none of them connected, as far as we can see, but all of them signs.”

“Signs?”

“Of a discontented people.”

“Henry Percy?” I repeat. “How was his death a sign? I thought people were objecting to paying tax?”

The king’s face is grim. “The people of the North never forgave him for failing Richard at Bosworth,” he says, watching me. “So I daresay you too think it serves him right.”

I don’t reply to this, it is still too raw for me. Henry Percy told Richard that his troops were too tired to fight, having marched from the North—as if a commander brings troops to a battle who are too tired to fight! He put himself at the rear of Richard’s army and never moved forwards. When Richard charged off the hill to his death, Percy watched him go without stirring himself. I won’t grieve for him in his dirty little death. He’s no loss to me. “But none of this has anything to do with my mother,” I hazard.

Uncle Jasper gives me a long, cool look from his blue eyes as if he disagrees.

“Not directly,” Henry concedes. “She shot her last bolt with the kitchen boy’s rebellion. I’ve got nothing that identifies her with these scattered troubles.”

“So she could come into confinement with me.”

“Very well,” he decides. “She’s as safe inside with you as she is inside the abbey. And it shows that she is a member of our family, to anyone who still dreams that she represents York.”

“May I write to her today?”

He nods, takes my hand, and kisses it. “I can refuse you nothing,” he says. “Not when you are about to give me another son.”

“What if it’s a girl?” I ask, smiling at him. “Will you send me a bill for all these favors if I have a girl?”

He shakes his head. “It’s a boy. I am certain of it.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, NOVEMBER 1489

“I wouldn’t bring it in on you,” she says when she finally comes in through the door, padded for silence, which opens so rarely on the outside world.

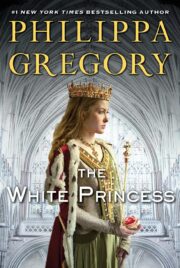

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.