“Have you heard of this new illness in the City?” I ask her.

“Yes, for the king has decided he can’t have his coronation and risk bringing together so many people who could be sick,” she says. “Henry will have to be a conqueror and not a crowned king for a few more weeks until the sickness passes. His mother, Lady Margaret, is having special prayers said; she will be beside herself. She thinks that God has guided her son this far, but now sends a plague to try his fortitude.”

Looking up at her, I have to squint against the bright western sky, where the sun is setting in a blaze of color, promising another unseasonably hot day tomorrow. “Mother, is this your doing?”

She laughs. “Are you accusing me of witchcraft?” she asks. “Cursing a nation with a plague wind? No, I couldn’t make such a thing happen; and if I did have such a power, I wouldn’t use it. This is a sickness that came with Henry because he hired the worst men in Christendom to invade this poor country, and they brought the disease from the darkest, dirtiest jails of France. It’s not magic, it’s men carrying illness with them as they march. That’s why it started first in Wales and then came to London—it has followed his route, not by magic but by the dirt they left behind them and the women they raped on the way, poor souls. It is Henry’s convict army which has brought the sickness, though everyone is taking it as a sign that God is against him.”

“But could it be both?” I ask. “Both a sickness and a sign?”

“Without doubt it is both,” she says. “They are saying that a king whose reign starts with sweat will have to labor to keep his throne. Henry’s sickness is killing his friends and supporters as if the disease were a weapon against him and them. He is losing more allies now in his triumph than ever died on the battlefield. It would be funny if it weren’t so bitter.”

“What does it mean for us?” I ask.

She looks upstream, as if the very water of the river might float an answer to my dangling feet. “I don’t know yet,” she says thoughtfully. “I can’t tell. But if he were to take the sickness himself and die, then people would be sure to say it was the judgment of God on a usurper, and would look for a York heir to the throne.”

“And do we have one?” I ask, my voice barely audible above the lapping of the water. “A York heir?”

“Of course we do: Edward of Warwick.”

I hesitate. “Do we have another? Even closer?”

Still looking away from me she nods, imperceptibly.

“My little brother Richard?”

Again she nods, as if she does not even trust the wind with her words.

I gasp. “You have him safe, Mother? You’re sure of it? He’s alive? In England?”

She shakes her head. “I have had no news. I can say nothing for certain, and certainly nothing to you. We have to pray for the two sons of York, Prince Edward and Prince Richard, as lost boys, until someone can tell us what has become of them.” She smiles at me. “And better that I don’t tell you what I hope,” she says gently. “But who knows what the future will bring if Henry Tudor dies?”

“Can’t you wish it on him?” I whisper. “Let him die of the illness that he has brought in with him?”

She turns her head away, as if to listen to the river. “If he killed my son, then my curse is already on him,” she says flatly. “You cursed the murderer of our boys with me, remember? We asked Melusina, the goddess-ancestor of my mother’s family, to take revenge for us. D’you remember what we said?”

“Not the exact words. I remember that night.”

It was the night when my mother and I were distraught with grief and fear, imprisoned in sanctuary as my uncle Richard came and told her that both her sons, Edward and Richard, my beloved little brothers, had disappeared from their rooms in the Tower. That was the night that my mother and I wrote a curse on a piece of paper, folded it into a paper boat, lit it, and watched it flare as it floated downriver. “I don’t remember exactly what we said.”

She knows it word for word, the worst curse she has ever laid on anyone; she has it by heart. “We said: ‘Know this: that there is no justice to be had for the wrong that someone has done to us, so we come to you, our Lady Mother, and we put into your dark depths this curse: that whoever took our firstborn son from us, that you take his firstborn son from him.’ ”

She turns her glance from the river to me, her pupils darkly dilated. “Do you remember now? As we sit here by the river? The very same river?”

I nod.

“We said: ‘Our boy was taken when he was not yet a man, not yet king—though he was born to be both. So take his murderer’s son while he is yet a boy, before he is a man, before he comes to his estate. And then take his grandson too and when you take him, we will know by these deaths that this is the working of our curse and this is payment for the loss of our son.’ ”

I give a shiver at the trance my mother is weaving around us as her quiet words fall on the river like rain. “We cursed his son and his grandson.”

“He deserves it. And when his son and his grandson die and he has nothing left but girls, then we will know him for the murderer of our boy, Melusina’s boy, and we will have had our revenge.”

“That was an awful thing that we did,” I say uncertainly. “A terrible curse on the innocent heirs. A terrible thing to wish the death of two innocent boys.”

“Yes,” my mother agrees calmly. “It was. And we did it because someone did it to us. And that someone will know my pain when his son dies, and when his grandson dies and he has no one but a girl left to inherit.”

People have always whispered that my mother practices witchcraft, and indeed her own mother was tried and found guilty of the dark arts. Only she knows how much she believes, only she knows what she can do. When I was a girl, I saw her call up a storm of rain, and I watched the river rise that washed away the Duke of Buckingham’s army and his rebellion with it. I thought then that she had done it all with a whistle. She told me of a mist which she breathed out one cold night which hid my father’s army, shrouding it so that he thundered out of a cloud on the hilltop and caught his enemy by surprise and destroyed them with sword and storm.

People believe that she has unearthly powers because her mother came from the royal house of Burgundy, and they can trace their ancestry back to the water witch Melusina. Certainly we can hear Melusina singing when one of her children dies. I have heard her myself, and it’s a sound I won’t forget. It was a cool, soft call, night after night, and then my brother was not playing on Tower Green anymore, his pale face was gone from the window, and we mourned for him as a dead boy.

What powers my mother has, and what luck runs her way that she claims as her doing, is unknown, perhaps even to her. Certainly she takes her good luck and calls it magic. When I was a girl, I thought her an enchanted being with the power to summon the rivers of England; but now, as I look at the defeat of our family, the loss of her son, and the mess we are in, I think that if she does conjure magic, then she can’t do it very well.

So I am not surprised that Henry does not die, though the sickness he has brought to England takes first one Lord Mayor of London, and then his hastily elected successor, and then six aldermen die too, almost in the same month. They say that every home in the city has suffered a death, and the carts for the dead rattle down the streets every night, just as if it were a plague year, and a bad one at that.

When the illness dies out with the cold weather, Jennie my maid does not come back to work when I send for her, for she is dead too; her whole household took the sweat and died of it between Prime and Compline. No one has known such quick deaths before, and they whisper everywhere against the new king whose reign has started with a procession of death carts. It is not till the end of October that Henry decides that it is safe to call the lords and genty of the realm together to Westminster Abbey to his coronation.

Two heralds bearing the Beaufort standard, the portcullis, and a dozen guards wearing the Stanley colors, hammer on the great door of the palace to inform me that Lady Margaret Stanley of the Beaufort family, My Lady the King’s Mother, is to honor me with a visit tomorrow. My mother inclines her head at the news and says softly—as if we are too nobly bred to ever raise our voices—that we will be delighted to see Her Grace.

As soon as they are gone and the door closed behind them, we fall into a frenzy about my dress. “Dark green,” my mother says. “It has to be dark green.”

It is our only safe color. Dark blue is the royal color of mourning, but I must not, for one moment, look as if I am grieving for my royal lover and the true king of England. Dark red is the color of martyrdom, but also sometimes, contradictorily, worn by whores to make their complexions appear flawlessly white. Neither association is one we want to inspire in the stern mind of the strict Lady Margaret. She must not think that marriage to her son is a torment for me, she must forget that everyone said that I was Richard’s lover. Dark yellow would be all right—but who looks good in yellow? I don’t like purple and anyway it is too imperial a color for a humbled girl whose only hope is to marry the king. Dark green it has to be and since it is the Tudor color, this can do nothing but good.

“But I don’t have a dark green gown!” I exclaim. “There isn’t time to get one.”

“We had one made for Cecily,” my mother replies. “You’ll wear that.”

“And what am I supposed to wear?” Cecily protests mutinously. “Am I to come in an old gown? Or will I not appear at all? Is Elizabeth going to be the only one who meets her? Are the rest of us to be in hiding? D’you want me to go to bed for the day?”

“Certainly, there’s no need for you to be here,” my mother says briskly. “But Lady Margaret is your godmother, so you will wear your blue and Elizabeth can wear your green, and you will make an effort—an exceptional effort—to be pleasant to your sister during the visit. Nobody likes a bad-tempered girl, and I have no use for one.”

Cecily is furious at this, but she goes to the chest of clothes in silence and takes out her new green gown, shakes it out, and hands it to me.

“Put it on and come to my rooms,” my mother says. “We’ll have to let down the hem.”

Dressed in the gown, now hemmed and trimmed with a new thin ribbon of cloth of gold, I wait in the presence chamber of my mother’s rooms for the arrival of Lady Margaret. She comes by royal barge, now always laid on for her convenience, with the drummer beating to keep the time, and her standards fluttering brightly at prow and stern. I hear the crunching footsteps of her companions on the gravel of the garden paths, then beneath the window, and then the clatter of the metal heels of their boots on the stones of the courtyard. They throw open the double doors and she comes through the lobby and into the room.

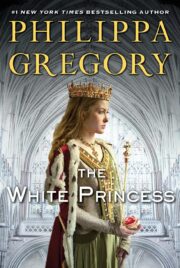

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.