“I can’t help but wish he was alive,” I say weakly. I look over at my adorable brown-headed son, jumping up to the mounting block to his pony, bright with excitement, and I remember my golden-haired little brother who was as brave and as joyous as Arthur, raised in a court filled with confidence.

“Then you do yourself and your line a disservice. I can’t help but wish him dead.”

I excuse myself from the day’s hawking and instead I take the royal barge and go down the river to Bermondsey Abbey. Someone sees the barge coming in, and runs for my mother to tell her that her daughter the queen is on her way, so she is on the little pier as we land, and comes to meet me, walking through the rowers, who stand at attention, their oars raised in salute, as if she still commanded them, a little nod to one side and the other, a little smile, easy in her authority. She curtseys to me at the gangplank and I kneel for her blessing and bob up.

“I have to talk with you,” I say tersely.

“Of course,” she says. She leads the way into the abbey’s central garden, sheltered by the high warm walls, and gestures to a seat built into a corner, overhung with an old plum tree. Awkwardly I stand, but I nod that she should sit down. The autumn sun is warm; she has a light shawl around her shoulders as she sits before me, her hands clasped lightly in her lap, and listens.

“The king says that you will know all about it already; but there is a boy calling himself by the name of my brother, landed in Ireland,” I say in a rush.

“I don’t know all about it,” she says.

“You know something about it?”

“I know that much.”

“Is he my brother?” I ask her. “Please, Lady Mother, don’t put me off with one of your lies. Please tell me. Is it my brother Richard in Ireland? Alive? Coming for his throne? For my throne?”

For a moment she looks as if she is going to prevaricate, turn the question aside with a clever word, as she always does. But she looks up at my white, strained face, and she puts out her hand to draw me down to sit beside her. “Is your husband afraid again?”

“Yes,” I breathe. “Worse than before. Because he thought it was over after the battle at Stoke. He thought he had won then. Now he thinks he will never win. He is afraid, and he is afraid of being afraid. He thinks he will always be afraid.”

She nods. “You know, words, once spoken, cannot be recalled. If I answer your question you will know things that you should tell your husband and his mother at once. And they will ask you these things explicitly. And once they know that you know them, they will think of you as an enemy. As they think me. Perhaps they would imprison you, as they have imprisoned me. Perhaps they would not allow you to see your children. Perhaps they are so hard-hearted that they would send you far away.”

I sink to my knees before her, and I put my face in her lap, as if I were still her little girl and we were still in sanctuary and certain to fail. “Am I not to ask?” I whisper. “He is my little brother. I love him too. I miss him too. Shall I not even ask if he is alive?”

“Don’t ask,” she advises me.

I look up at her face, still beautiful in this afternoon golden light, and I see that she is smiling. She is a happy woman. She does not look at all like a woman who has lost two beloved sons to an enemy, and knows that she will never see either of them again.

“But you hope to see him?” I whisper.

The smile she turns to me is filled with joy. “I know I will see him,” she says with absolute serene conviction.

“In Westminster?” I whisper.

“Or in heaven.”

Henry comes to my rooms after dinner. He does not sit with his mother this evening, but comes directly to me and listens to the musicians play and watches the women dance, takes a hand at cards and rolls some dice. Only when the evening ends and the people make their bows and their curtseys and withdraw does he pull up his chair before the great fire in my presence chamber, snap his fingers for another chair to be placed beside him, and gesture that I shall sit with him, and that everyone but a servant, standing at the servery, shall leave us.

“I know that you went to see her,” he says without preamble.

The man pours a tankard of mulled ale and puts a small glass of red wine on a table beside me, and then makes himself scarce.

“I took the royal barge,” I say. “It was no secret.”

“And you told her of the boy?”

“I did.”

“And did she know already?”

I hesitate. “I think so. But she could have learned it from gossip. People are starting to talk, even in London, about the boy in Ireland. I heard about it in my own rooms tonight; everyone is talking, again.”

“And does she believe that this is her son, returned from the dead?”

Again I pause. “I think that she may do. But she is never clear with me.”

“She is unclear because she is engaged in treason against us? And does not dare to confess?”

“She is unclear because she has a habit of discretion.”

He laughs abruptly. “A lifetime of discretion. She killed the sainted King Henry in his sleep, she killed Warwick on the battlefield shrouded in a witch’s mist, she killed George in the Tower of London drowned in a barrel of sweet wine, she killed Isabel his wife and Anne, the wife of Richard, with poison. She has never been accused of any of these crimes, they are still secret. She is indeed discreet, as you say. She’s murderous and discreet.”

“None of that is true,” I say steadily, disregarding the things that I think may be true.

“Well, at any rate . . .” He stretches his boots towards the fire. “She did not tell you anything that would help us? Where the boy comes from? What are his plans?”

I shake my head.

“Elizabeth . . .” His voice is almost plaintive. “What am I to do? I can’t keep fighting for England. The men who came out for me at Bosworth didn’t all turn out for me at the battle of Stoke. The men who risked their lives at Stoke won’t come out for me again. I can’t go on fighting for my life, for our lives, year after year. There is only one of me, and there are legions of them.”

“Legions of who?” I ask.

“Princes,” he says, as if my mother had given birth to a monstrous dark army. “There are always more princes.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, DECEMBER 1491

He is spending the Christmas celebrations as the guest of the Irish lords in one of their faraway castles. There will be feasting and dancing, they will toast to their victory. He will feel invincible as they drink to his health and swear that they cannot fail.

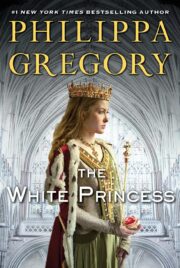

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.