“What d’you think?” Henry says grimly, dropping this smooth account into my lap as I sit in the nursery, admiring the new baby, who is feeding greedily from the sleepy wet nurse, one little hand patting the plump blue-veined breast, one little foot waving with pleasure.

I read the letter. “Did he write this to you?” I put my hand on the cradle, as if I would protect her. “He didn’t write to me?”

“He didn’t write this to me. But God knows, he’s written to everyone but us.”

I can feel my heart thud. “He hasn’t written to us?”

“No,” Henry says, suddenly eager. “That counts against him, doesn’t it? He should have written to you? To your mother? Wouldn’t a lost son, wanting to come home, have written to his mother?”

I shake my head. “I don’t know.”

Carefully neither of us remark that this boy almost certainly wrote to her, and she certainly replied.

“Will anyone have told him that his—” I break off “—that my mother is dead?”

“For sure,” Henry says grimly. “I don’t doubt he has many faithful correspondents from our court.”

“Many?”

He nods. I cannot tell if he is speaking from his darkest fears or from terrible knowledge of traitors who live with us and daily curtsey or bow and yet secretly write to the boy. In any case, the boy should know that my mother is dead, and I am glad that someone has told him.

“No, this is his letter to the Spanish king and queen, Ferdinand and Isabella,” Henry goes on. “My men picked it up on the way to them and copied it and sent it on.”

“You didn’t destroy it? To prevent them seeing it?”

He grimaces. “He has sent out so many letters that destroying just one would make no difference. He tells a sad tale. He spins a good yarn. People seem to believe it.”

“People?”

“Charles VIII of France. He’s a boy himself, and all but a madman. But he believes this shadow, this ghost. He’s taken the boy in.”

“In where?”

“Into his court, into France, into his protection.” Henry bites off his answer and looks angrily at me. I gesture to the wet nurse, commanding her to take the baby from the room, as I don’t want our little Princess Elizabeth to hear of danger, I don’t want her to hear the fear in our voices when she should be feeding peacefully.

“I thought you had ships off Ireland to prevent him leaving?”

“I had Pregent Meno offer him a safe voyage. I had ships off Ireland to capture him if he took another vessel. But he saw through the trap of Pregent Meno, and the French sent ships of their own and they smuggled him out.”

“To where?”

“Honfleur—does it make any difference?”

“No,” I say. But it makes a difference to my imagining. It is as if I can see the dark sea, dark as my Elizabeth’s eyes, the swirling mist, the failing light, and the little boats slipping into an unknown Irish port and then the boy—the handsome young boy in his fine clothes—stepping lightly on the gangplank, turning his face into the wind, heading for France with his hopes high. In my imagining, I see his golden hair lift off his young forehead and I see his bright smile: my mother’s indomitable smile.

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, SUMMER–AUTUMN 1492

Brittany—the little independent dukedom that housed and hid Henry during his years when he was a penniless pretender to the throne—is at war with its mighty neighbor of France and has called on Henry for help. I cannot help but smile to see my husband in this quandary. He wants to be a great warrior king as my father was—but he has a great disinclination to go to war. He owes a debt of honor to Brittany—but war is the most costly undertaking and he cannot bear to waste money. He would be glad to defeat France in a battle—but Henry would hate to lose such a battle, and he cannot tolerate risk. I do not blame him for his caution. I saw our family destroyed by the outcome of a battle, I have seen England at war for most of my childhood. Henry is wise to be cautious; he knows that there is no glory on the battlefield.

Even as he is arming and planning the invasion of France he is puzzling how to avoid it, but at the end of the summer he makes up his mind that it has to be done, and in September we leave the palace in a great procession, Henry in his armor on his great warhorse, the circlet of England fixed on his helmet as if it has never been anywhere else. It is the crown that Sir William Stanley wrenched from Richard’s helmet, when he dragged it from his battered head. I look at it now, and I fear for Henry, going to war wearing this unlucky crown.

We leave the younger children with their nurses and teachers in Greenwich, but Arthur, who is nearly six years old, is allowed to ride out with us on his pony and watch his father set off for war. I leave the new baby, little Elizabeth, reluctantly. She is not thriving, not on the wet nurse’s milk nor on the sops of bread dipped in the juice of meat that the doctors say will strengthen her. She does not smile when she sees me, as I am sure Arthur did at her age, she does not kick and rage as Henry did. She is quiet, too quiet I think, and I don’t want to leave her.

I say none of these thoughts to Henry and he will not speak of fear. Instead, we go as if we are traveling on a wonderful progress through the county of Kent where the apples are thick in the orchards and the oasthouses are free with ale. We travel with musicians who play for us when we stop to dine in exquisite embroidered tents set up beside rivers, on beautiful hillsides or deep in the greenwood. Behind us comes an enormous cavalry—sixteen hundred horses and knights, and after them come the footsoldiers, twenty-five thousand of them, and all of them well shod and sworn to Henry’s service.

It reminds me of when my father was King of England and he would lead the court on a great progress around the grand houses and priories. For this short time we look like my parents’ heirs: we are young and blessed with good luck and wealth. In the eyes of everyone we are as beautiful as angels, dressed in cloth of gold, riding behind waving standards. Beside us is the flower of England; all the greatest men are Henry’s commanders, and their wives and daughters are in my train. Behind them is a great army, mustered for Henry against an enemy they all hate. The summer weather smiles on us, the long sunny days invite us to ride out early and rest in the midday heat beside the glorious rivers or in the shade of the greenwood. We look like the king and queen that we should be, the center of beauty and power in this beautiful and powerful land.

I see Henry’s head rise up with dawning pride as he leads this mighty army through the heart of England; I see him start to ride like a king going to war. When we go through the little towns on the way and people call out for him, he lifts his gauntleted hand and waves, smiling back in greeting. At last he has found his pride in himself, at last he has found his confidence. With a greater army behind him than this part of England has ever seen, he smiles like a king who is firm on his throne, and I ride beside him and feel that I am where I should be: the beloved queen of a powerful king, a woman as richly blessed as my own lucky mother.

At night he comes to my room in an abbey or in a great house on the way, and he wraps his arms around me as if he is sure of his welcome. For the first time in our marriage I turn my head towards him, not away, and when he kisses me I put my arms on his broad shoulders and hold him close, offering him my mouth, my kiss. Gently, he puts me down on the bed and I don’t turn my face to the wall but I wrap my arms around him, my legs around him, and when he enters me, I ripple with the sensation of pleasure and welcome his touch for the first time in our marriage. In Sandwich Castle, for the first time ever, he comes naked to me and I move with him, consenting, and then inviting, and then finally begging him for more and he feels me melt beneath him as I hold him and cry out in pleasure.

We make love all night, as if we were newly married and newly discovering the beauty of each other’s body. He holds me as if he will never leave me, and in the morning he carries me over to the window, wrapped in a fur, and kisses my neck, my shoulders, and finally my smiling lips, as we watch the Venetian galleys slicing their oars through the harbor water as they come in, to take his troops to France.

“Not so soon, not today! I can’t bear to let you go,” I whisper.

“That you should love me like this now!” he exclaims. “I have been waiting for this ever since I first met you. I have dreamed that you might want me, I have come to your bed night after night longing for your smile, hoping that there would come a night when you would not turn away.”

“I’ll never turn away again,” I swear.

The joy in his face is unmistakable, he looks like a man in love for the first time.

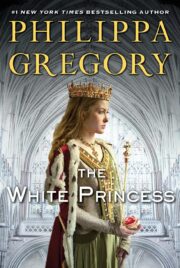

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.