“The boy!” he repeats.

I look at our own boys, Arthur walking solemnly ahead in black velvet and Harry, just starting to toddle with his nursemaid holding his hand and veering around the path as he goes to left or right or stops abruptly for a leaf or a piece of gravel. If he takes too long she will scoop him up; the king wants to walk unimpeded. The king must stride along, his two boys going ahead of him to show that he has an heir, two heirs, and his house is established.

“Elizabeth is not very well,” I tell him. “She lies too quietly, and she does not kick or cry.”

“She will,” he says. “She’ll grow strong. Dear God, you have no idea what it means to me, that I have the boy.”

“The boy,” I say quietly. I know that he is not speaking of either of our boys. He means the boy who haunts him.

“He’s at the French court, treated like a lord,” Henry says bitterly. “He has his own court around him, half of your mother’s friends and many of the old York royal household have joined him. He’s housed with honor, good God! He sleeps in the same room as Charles, the King of France, bedfellow to a king—why not, since he is known everywhere as Prince Richard? He rides out with the king, dressed in velvets, they hunt together, they are said to be the greatest of friends. He wears a red velvet cap with a ruby badge and three pendant pearls. Charles makes no secret of his belief that the boy is Richard. The boy carries himself like a royal duke.”

“Richard.” I repeat the name.

“Your brother. The King of France calls him Richard Duke of York.”

“And now?” I ask.

“As part of the peace treaty which I have won for us—it’s a great peace treaty, better value for me than any French town, far better than Boulogne—Charles has agreed to hand over to me any English rebel, anyone conspiring against me. And I to him, of course. But we both know what we mean. We both know who we mean. We both only mean one person, one boy.”

“What will happen?” I ask quietly, but my face is chilled in the cold November weather and I feel that I want to go inside, out of the wind, away from my husband’s hard, exultant face. “What will happen now?”

I begin to wonder if the whole war, the siege of Boulogne, the sailing of so many ships, the mustering of so many men, was just for this? Has Henry become so fearful that he would launch an armada to capture just one boy? And if so, is this not a form of madness? All this, for one boy?

My Lady the King’s Mother and the whole court are waiting in rows according to their rank, before the great double door of the palace. Henry goes forwards and kneels before her for her blessing. I see the triumphant beam on her pale face as she puts her hand on his head, and then raises him up to kiss him. The court cheers and comes forwards to bow and congratulate him. Henry turns from one to another, accepting their praise and thanks for his great victory. I wait with Arthur until the excitement has died down and Henry comes back to my side, flushed with pleasure.

“King Charles of France is going to send him to me,” Henry continues in an undertone, beaming as people walk past us, going into the palace, pausing to sweep a curtsey or make a deep bow. Everyone is celebrating as if Henry has triumphed in a mighty victory. My Lady is alight with joy, accepting congratulations for the military skill and courage of her son. “This is my prize of victory, this is what I have won. People talk about Boulogne; it was never about Boulogne. I don’t care that it didn’t fall under the siege. It was not to win Boulogne that I went all that way. It was to frighten King Charles into agreeing to this: the boy as a prisoner, sent to me in chains.”

“In chains?”

“Like a triumph, I shall have him come in, chained in a litter. Pulled by white mules. I shall have the curtains pinned back so that everyone can see him.”

“A triumph?”

“Charles has promised to send the boy to me chained.”

“To his death?” I ask quietly.

He nods. “Of course. I am sorry, Elizabeth. But you must have known it has to end like this. And anyway, you thought he was dead, for years you had given him up for dead—and now he will be.”

I take my hand from the warm crook of his arm. “I’m not well,” I say pitifully. “I’m going in.”

I am not even pretending to illness to avoid him in this mood; truly, I am nauseated. I sent a beloved husband out into danger and I have prayed every day for his safe return. I promised him that when he came home I would love him faithfully and passionately as we had just learned to do. But now, at the moment of his return, there is something about him that I think no woman could love. He is gloating in the defeat of a boy, he is reveling at the thought of his humiliation, he is hungrily imagining his death. He has taken an entire army over the narrow seas to win nothing but the torture and execution of one young orphan. I cannot see how I can admire such a man. I cannot see how to love such a man, how to forgive him for this single-minded hatred of a vulnerable boy. I shall have to think how to avoid naming this—even privately to myself—as a sort of madness.

He lets me go. His mother steps up beside him and takes my place as if she were only waiting for me to leave; and the two of them look after me as I go quickly into our favorite palace, which was built for happiness and dancing and celebration. I walk through the great hall where the servants are preparing huge trestle tables for Henry’s welcome victory banquet, and I think that it is a poor victory, if they only knew it. One of the greatest kings in Christendom has just taken out a mighty army and invaded another country for nothing but to entrap a lost boy, an orphan boy, into a shameful death.

We prepare for Christmas at Greenwich, the happiest, most secure Christmas that Henry has ever had. Knowing that the King of France has the boy in his keeping, knowing that his treaty with the King of France is strong and holding firm, Henry sends his envoys to Paris to bring the boy home for his execution and burial, watches the yule log dragged into the hall, pays the choirmaster extra for a new Christmas carol, and demands feasts and pageants, special dances and new clothes for everyone.

Me, he drapes me in swathes of silks and velvets and watches while the seamstresses pin and tuck the material around me. He urges them to trim the gowns with cloth of gold, with silver thread, with fur. He wants me shining with jewels, encrusted with gold lace. Nothing is too good for me this season, and my dresses are copied for my sisters and for my cousin Maggie, so that the women of the House of York glitter at court under the Tudor gilding.

It is like living with a different man. The terrible anxiety of the early years has melted away from Henry, and whether he is in the schoolroom interrupting lessons to teach Arthur to play dice, tossing Harry up in the air, dancing little Margaret around till she screams with laughter, petting Elizabeth in her cradle, or wasting his time in my rooms, teasing my ladies and singing with the musicians, he does not stop smiling, calling for entertainment, laughing at some foolish joke.

When he greets me at chapel in the morning he kisses my hand and then draws me to him and kisses me on the mouth, and then walks beside me with his arm around my waist. When he comes to my room at night he no longer sits and broods at the fireside, trying to see his future in the fading embers, but enters laughing, carrying a bottle of wine, persuades me to drink with him, and then carries me to my bed, where he makes love to me as if he would devour me, kissing every inch of my skin, nibbling my ear, my shoulder, my belly, and only finally sliding deep into me and sighing with pleasure as if my bed is his favorite place in all the world, and my touch is his greatest pleasure.

He is free at last to be a young man, to be a happy man. The long years of hiding, of fear, of danger seem to slide away from him and he begins to think that he has come to his own, that he can enjoy his throne, his country, his wife, that these goods are his by right. He has won them, and nobody can take them from him.

The children learn to approach him, confident of their welcome. I start to joke with him, play games of cards and dice with him, win money from him and put my earrings down as a pledge when I up the stakes, making him laugh. His mother does not cease her constant attendance at chapel but she stops praying so fearfully for his safety and starts to thank God for many blessings. Even his uncle Jasper sits back in his great wooden chair, laughs at the Fool and stops raking the hall with his hard gaze, ceases staring into dark corners for a shadowy figure with a naked blade.

And then, just two nights before Christmas, the door to my bedchamber opens and it is as if we had fallen back to the early years of our marriage and all the happiness and easiness is gone in a moment. A frost has fallen; the habitual darkness comes in with him. He enters with a quick cross word to his servant, who was following with glasses and a bottle of wine. “I don’t want that!” he spits, as if it is madness even to suggest it, he has never wanted such a thing, he would never want such a thing; and the man flinches and goes out, closing the door, without another word.

Henry drops into the chair at my fireside and I take a step towards him, feeling the old familiar sense of apprehension. “Is something wrong?” I ask.

“Evidently.”

In his sulky silence, I take the seat opposite him and wait, in case he wants to speak with me. I scan his face. It is as if his joy has shut down, before it had fully flowered. The sparkle has gone from his dark eyes, the color has even drained from his face. He looks exhausted, his skin is almost gray. He sits as if he were a much older man, plagued with pain, his shoulders strained, his head set forwards as if he were pulling against a heavy load, a tired horse, cruelly harnessed. As I watch him he puts his hand over his eyes as if the glow from the fire is too bright against the darkness within, and I am moved with sudden deep pity. “Husband, what is wrong? Tell me, what has happened?”

He looks up at me as if he is surprised to find that I am still there, and I realize that his reverie was so deep that he was far away from my quiet warm chamber, straining to see a room somewhere else. Perhaps he was even trying to see back into the darkness of the past, to the room in the Tower and the two little boys sitting up in their bed in their nightshirts as their door creaked open and a stranger stood in the entrance. As if he is longing to know what happens next, as if he fears to see a rescue, and hopes to see a murder.

“What?” he asks irritably. “What did you say?”

“I can see that you are troubled. Has something happened?”

His face darkens and for a moment I think he will break out and shout at me, but then the energy drains from him as if he were a sick man. “It’s the boy,” he says wearily. “That damned boy. He’s disappeared from the French court.”

“But you sent . . .”

“Of course I sent. I have had half a dozen men watching him the moment he arrived in the French court from Ireland. I have had a dozen men following him since King Charles promised him to me. Do you think I am an idiot?”

I shake my head.

“I should have ordered them to kill him then and there. But I thought it would be better if they brought him back to England for execution. I thought we would hold a trial where I would prove him to be an imposter. I thought I would create a story for him, a shameful story about poor ignorant parents, a drunk father, a dirty occupation somewhere on a river near a tannery, anything to take the shine off him. I thought he would be sentenced to execution and I would have everyone watch him die. So that they would all know, once and for all, that he is dead. So that everyone would stop mustering for him, plotting for him, dreaming of him . . .”

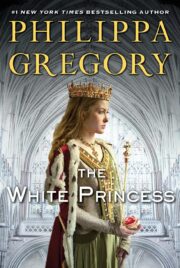

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.