“But he’s gone? Run away?” I can’t help it; whoever he is, I hope that the boy has got away.

“I said so, didn’t I?”

I wait for a few moments as his ill-tempered snarl dies away and then I try again. “Gone where?”

“If I knew that, I would send someone to kill him on the road,” my husband says bitterly. “Drown him in the sea, drop a tree on his head, lame his horse, and cut him down. He could have gone anywhere, couldn’t he? He’s quite the little adventurer. Back to Portugal? They believe he is Richard there, they refer to him as your father’s son, the Duke of York. To Spain? He has written to the king and queen as an equal and they have not contradicted him. To Scotland? If he goes to the King of Scots and together they raise an army and come against me, then I am a dead man in the North of England; I don’t have a single friend in those damned bleak hills. I know the Northerners; they are just waiting for him to lead them before they rise against me.

“Or has he gone back to Ireland to rouse the Irish against me again? Or has he gone to your aunt, your aunt Margaret in Flanders? Will she greet her nephew with joy and set him up against me, d’you think? She sent a whole army for a kitchen boy, what will she do for the real thing? Will she give him a couple of thousand mercenaries and send him to Stoke to finish off the job that her first pretender started?”

“I don’t know,” I say.

He leaps to his feet and his chair crashes back on the floor. “You never know!” he yells in my face, spittle flying from his mouth, beside himself with anger. “You never know! It’s your motto! Never mind ‘humble and penitent,’ your motto is ‘I don’t know! I don’t know! I never know!’ Whatever I ask you, you always never know!”

The door behind me opens a crack, and my cousin Maggie puts her fair head into the room. “Your Grace?”

“Get out!” he yells at her. “You York bitch! All of you York traitors. Get out of my sight before I put you in the Tower along with your brother!”

She flinches back from his rage but she will not leave me to his anger. “Is everything all right, Your Grace?” she asks me, forcing herself to ignore him. I see she is clinging to the door to hold herself up, her knees weak with fear, but she looks past my furious husband to see if I need her help. I look at her white face and know that I must look far worse, ashen with shock.

“Yes, Lady Pole,” I say. “I am quite all right. There is nothing for you to do here. You can leave us. I am quite all right.”

“Don’t bother on my account, I’m going!” Henry corrects me. “I’m damned if I’ll spend the night here. Why would I?” He rushes to the door and jerks it away from Maggie, who staggers for a moment but still holds her ground, visibly trembling. “I’m going to my own rooms,” he says. “The best rooms. There’s no comfort for me here, in this York nest, in this foul traitors’ nest.”

He storms out. I hear the bang in the outer presence chamber as they ground their pikes as he tears open the door, and then the scuffle as his guard hastily fall in behind him to follow him. By tomorrow, the whole court will know that he called Margaret a York bitch and me a York traitor, that he said my rooms were a foul traitors’ nest. And in the morning everyone will know why: the boy who calls himself my brother has disappeared again.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, SPRING 1493

She writes to everyone, in an explosion of gladness, telling them that the age of miracles is not over, for here is her nephew who was given up for dead, walking among us like an Arthur awakened from sleep and returned to Camelot.

The monarchs of Christendom reply to her. It is extraordinary, but if she recognizes her nephew, then who can deny him? Who could know better than his own aunt? Who would dare to tell the Dowager Duchess of Burgundy that she is mistaken? Anyway, why should she be mistaken? She sees in this boy the certain features of her nephew, and she tells everyone that she knows him for her brother’s son. None of her dear friends, the Holy Roman Emperor, the King of France, the King of Scotland, the King of Portugal, and the monarchs of Spain, deny him for a moment. And the boy himself: everyone reports that he is princely, handsome, smiling, composed. Dressed in the best clothes that his wealthy aunt can have made for him, creating his own court from the increasing numbers of men who join him, he speaks sometimes of his childhood and refers to events that only a child at my father’s court could know. My father’s servants, my mother’s old friends escape from England as if it is now an enemy country. They make their way to Malines to see him for themselves. They put to him the questions they have composed to test him. They scan his face for any resemblance to the pretty little prince that my mother adored, they try to entrap him with false memories, with chimeras. But he answers them confidently, they believe him too, and they stay with him. They all are satisfied with their own tests. Every single one of them, even those who set out to disprove him, even those who were paid by Henry to embarrass him, are convinced. They fall to their knees, some of them weep, they bow to him, as to their prince. It is Richard, back from the dead, they write back to England in delight. It is Richard, snatched from the very jaws of death, the rightful King of England restored to us once more, returned to us once more, the son of York shining again.

More and more people start to slip away from the households of England. William, the king’s favorite farrier, is missing from the forge. Nobody can understand why he would leave the favor of the court, the shoeing of the finest horses in the kingdom, the patronage of the king himself—but the fire is out and the forge is dark and the whisper is that William has gone to shoe the horses of the true King of England, and won’t stay with a Tudor pretender any longer. A group of neighbors who live near to my grandmother Duchess Cecily disappear from their handsome homes in Hertfordshire, and travel in secret to Flanders, almost certainly with her blessing. Priests go missing from their chapels, their clerks forward letters to known sympathizers, couriers take money from houses in England to the boy. Then, worst of all, Sir Robert Clifford, a lifelong courtier for York, a man trusted by Henry to be his envoy to Brittany, packs his bags with Tudor treasures and goes. His place is empty in our chapel, his table is not prepared for dinner in our hall. Shockingly, unbelievably, our friend Sir Robert with his entire household has disappeared; and everyone knows he has gone to the boy.

Then it is we who look like a court of pretenders. The boy looks and sounds like the real thing while we pretend to confidence; but I see the strain in the face of My Lady the King’s Mother and the way that Jasper Tudor stalks the halls like an old warhorse, nervously, his hand drifting towards his belt where his sword should be, always watching the hall when he eats, always alert to the opening of a door. Henry himself is gray with fatigue and fear. He starts his working day at dawn, and all day men come into the small room in the center of the palace where he meets his advisors and his spies with a double guard on the door.

The court is hushed; even in the nursery where there should be spring sunshine and laughter, the nurses are quiet and they forbid the children to shout or run around. Elizabeth is sleepy and still in her cradle. Arthur is all but silent; he does not know what is happening but he senses that he is living in a palace under siege, he knows that his place is threatened, but he has been told nothing about the young man whose nursery this was, who did his lessons at this very table. He does not know of a Prince of Wales who preceded him, who was studious and thoughtful and the darling of his mother, too.

His sister Margaret is guarded. She is quiet as they order her to be as if she knows that something is wrong, but does not know what to do.

Their little brother Harry is starting to insist on having his own way, a stout little boy with a shouting laugh and a love of games and music; but even he is quietened by the haste and anxiety of the palace. Nobody has time to play with him anymore, nobody will pause to talk with him as they move swiftly through the great hall, busy with secret business. He looks around in bewilderment at the people who only a few months ago would always stop and swing him up to the ceiling, or toss a ball for him, or take him down to the stable to see a horse, but who now frown and hurry past.

“S’ William!” he calls to Thomas Stanley’s brother as he walks by. “Harry too!”

“You can’t,” Sir William says shortly, and he looks at Harry coldly, and goes on to the stables, so the child stops short and looks around for his nurse.

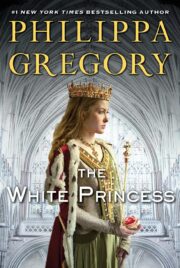

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.