“That’s all I have for now,” he says through gritted teeth. “As I said. What I don’t have I will write myself. I will write this boy’s parentage into his story, I will create it: common people, nasty people. The father a bit of a drunk, the mother a bit of a fool, the boy a bit of a runaway, a wastrel, a good-for-nothing. D’you think I can’t write this and get someone—a drunk married to a fool—to swear to it? Do you think I can’t set up as historian? As storyteller? D’you think I can’t write a history which years from now, everyone will believe as the truth? I am the king. Who shall write the record of my reign if not me?”

“You can say anything you like,” I say levelly. “Of course you can. You’re the King of England. But it doesn’t make it true.”

A few days later Maggie, my cousin, comes to me. Her husband has been made Arthur’s Lord Chamberlain, but they cannot take up residence in Wales while the west is threatened by a rival prince. “My husband, Sir Richard, tells me that the king has found a name for the boy.”

“Found a name? What do you mean, found a name?”

She makes a little face, acknowledging the oddness of the phrase. “I should have said, that the king now says he knows who the boy is.”

“And?”

“The king says he is to be called Perkin Warbeck, the son of a boatman. From Tournai, in Picardy.”

“Does he say that the boatman is a drunk, married to a fool?”

She does not understand me. She shakes her head. “He has nothing else but this name. He says nothing else.”

“And is he sending the boatman and his wife to Duchess Margaret? So that the boy can be faced by his parents and forced to confess? Is he taking the boatman and his wife to the kings and queens of Christendom so that they can show who he truly is, and claim their son back from these royal courts which have kept him for so long?”

Margaret looks puzzled. “Sir Richard didn’t say.”

“It’s what I’d do.”

“It’s what anyone would do,” she agrees. “So why is the king not doing it?”

Our eyes meet, and we say nothing more.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, WINTER 1493

“They said what?” Henry demands. He has ordered me into his presence chamber to hear this report from the returning ambassadors, but he does not greet me nor set a chair for me. I doubt he even sees me: he is blinded with rage. I sink down into my seat as he strides about, shaking with anger. The ambassadors throw a quick glance at me to see if I am going to intervene. I sit like a cold statue. I am going to say nothing.

“The heralds called him ‘Richard, son of Edward, King of England,’ ” the man repeats.

Henry rounds on me. “Do you hear this? Do you hear this?”

I incline my head. On the other side of the king I notice My Lady, his mother, lean forwards so that she can see me, as if she expects me to weep.

“Your dead brother’s name,” she reminds me. “Abused by this forger.”

“Yes,” I say.

“The new emperor, Maximilian, loves the ki—the boy,” the ambassador offers, flushing over the terrible slip. “They are together all the time. The boy represents the emperor when he meets with his bankers, speaks for him with his betrothed. He is the emperor’s principal friend and confidant. He is his only advisor.”

“Oh, and what did you call him?” Henry asks, as if it does not much matter.

“The boy.”

“What d’you call him when you see him at the emperor’s court? When he’s at the emperor’s side? When he is, as you describe, so central to the emperor’s happiness, at the heart of his court? His only friend and advisor? When you greet this youth of such great importance? What do you call him at court?”

The man shuffles, passes his hat from one hand to another. “It was important not to insult the emperor. He is young, and hotheaded, and he is the emperor, after all. He loves and respects the boy. He tells everyone of his miraculous escape from death, he constantly speaks of his high birth, of his rights.”

“So what did you call him?” Henry asks quietly. “When you were all in the emperor’s hearing?”

“Mostly I didn’t speak to him. We all avoided him.”

“But when you did? On those rare occasions. Those very rare occasions. When you had to?”

“I called him ‘my lord.’ I thought it was the safest thing to say.”

“As if he was a duke?”

“Yes, a duke.”

“As if he was Richard, Earl of Shrewsbury and Duke of York?”

“I never said Duke of York.”

“Oh, who do you think he is?”

This question is a mistake. Nobody knows who he is. The ambassador is silent, twisting the brim of his hat. He has not yet been primed with the story which we have learned by rote.

“He is Warbeck, the son of a Tournai boatman,” Henry says bitterly. “A nobody. His father is a drunk, his mother is a fool. And yet you humbled yourself and bowed to him? Did you call him ‘Your Grace’?”

The ambassador, uncomfortably aware that he will have been spied on in his turn, that the reports piled facedown on Henry’s table will include accounts of his meetings and conversations, flushes slightly. “I may have done. It’s how I would address a foreign duke. It wouldn’t mean that I respect his title. It wouldn’t indicate that I accept his title.”

“Or a king. Because you would call a king ‘Your Grace’?”

“I did not address him as a king, Sire,” the man says with steady dignity. “I never forgot that he is a pretender.”

“But he’s a pretender now with a powerful backer,” Henry breaks out, suddenly furious. “A pretender living with an emperor and announced to the world as Richard, son of Edward, King of England.”

For a moment everyone is too frightened to speak. Henry’s bulging gaze holds his frightened ambassador. “Yes,” the man concurs into the long silence. “That’s what everybody calls him.”

“And you did not deny him!” Henry bellows.

The ambassador is frozen like a statue of fear.

Henry exhales a shuddering sigh, and stalks back to his seat, pauses with his hand on the high carved back, stands under the cloth of estate as if to indicate to everyone his greatness. “So if he is King of England,” Henry says with slow menace, “what do they call me?”

Again the ambassador looks at me for help. I keep my eyes down. There is nothing I can do to divert Henry’s rage from him; it is all I can do to avoid being its target myself.

The silence lasts, then Henry’s ambassador finds the courage to tell him the truth. “They call you Henry Tudor,” he says simply. “Henry Tudor, the pretender.”

I am in my rooms, Elizabeth is quiet in the cradle beside me and my sewing is in my hand, but little work is being done. One of My Lady’s endless kinswomen is reading to us from a book of psalms, My Lady the King’s Mother nodding along to the well-known words as if they are somehow in her ownership, the rest of us silent, listening, our faces composed into expressions of pious reflection, our thoughts anywhere. The door opens and the commander of the yeomen of the guard stands there, his face grave.

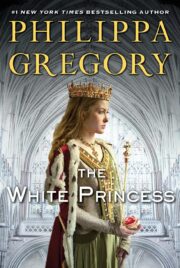

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.