My ladies gasp, and someone gives a little frightened scream. I rise slowly to my feet and look to my cousin Maggie. I see her lips working, as if she is about to speak, but she has lost her voice.

Slowly, I rise to my feet and find that I am trembling so that I can barely stand. Maggie takes two steps towards me, putting her hand under my elbow, holding me up. Together we face the man responsible for my safety who looms in my doorway, neither coming in nor announcing a visitor. He is silent as if he cannot bear to speak either. I feel Maggie shudder and I know she is thinking, as I am, that he has come to take us to the Tower.

“What is it?” I ask. I am glad that my voice is quiet and steady. “What is it, Commander?”

“I have to make a report to you, Your Grace,” he says. He looks awkwardly around the room as if he is uncomfortable at speaking in front of all the ladies.

The relief that he is not here to arrest me almost overwhelms me. Cecily, my sister, drops into her seat and gives a little sob. Maggie steps back and leans against my chair. My Lady the King’s Mother is unmoved. She beckons him in. “Enter. What is your report?” she says briskly.

He hesitates. I step towards him so he can speak to me quietly. “What is it?”

“It’s Yeoman Edwards,” he says. His face suddenly flushes as if he is ashamed. “I beg your pardon, Your Grace. It’s very bad.”

“Is he sick?” My first fear is of plague.

But My Lady has joined us and she is quicker than me. “Has he gone?”

The captain nods.

“To Malines?”

He nods again. “He told no one he was going, nor where his loyalties lay; I’d have arrested him at once if I’d had so much as a whisper. He’s been under my command, guarding your door for half a year. I never dreamed . . . Forgive me, Your Grace. But I had no way of knowing. He left a note for his girl, and that’s how we know. We opened it.” Hesitantly, he proffers a scrap of paper.

I have gone to serve Richard of York, true King of England. When I march in behind the white rose of York I will claim you for my bride.

“Let me see that!” Lady Margaret exclaims, and snatches it from my hand.

“You can keep it,” I say dryly. “You can take it to your son. But he won’t thank you for it.”

The look she turns on me is quite horrified. “Your own yeoman of the guard,” she whispers. “Gone to the boy. And Henry’s own groom has gone.”

“He has? I didn’t know.”

She nods. “Sir Ralph Hastings’s steward has gone and taken all the family’s silver to Malines. And Sir Edward Poynings’s own tenants . . . Sir Edward, who was our ambassador in Flanders, can’t keep his own men here. There are dozens of men, slipping away—hundreds.”

I glance back at my ladies. The reading has stopped and everyone is leaning forwards trying to hear what is being said; there is no mistaking the avidity on their faces, Maggie and Cecily among them.

The commander of my guard dips his head in a bow and steps backwards and closes the door behind him. But My Lady the King’s Mother rounds on me in a fury, flinging a pointing finger to my kinswomen.

“We married those girls—your sister and your cousin—to men we could trust, so that their interests would lie with us, to make them Tudors,” she hisses at me, as if it is my fault that they are eager for news. “Now we can’t be sure that their husbands aren’t hoping to rise as Yorks, and their interests go quite the other way. We married them to loyal nobodies, we gave men who had almost nothing a princess of York so that they would be true to us, so that they would be grateful. Now perhaps they think that they can take their makeshift wives and reach for greatness.”

“My family is faithful to the king,” I say staunchly.

“Your brother . . .” She swallows her accusation. “Your sister and your cousin have been established and enriched by us. Can we trust them? While everyone is running away? Or will they too use their fortune and their husbands against us?”

“You chose their husbands,” I say dryly into her white anxious face. “There’s no point complaining to me if you fear that your handpicked men are faithless.”

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, SUMMER 1494

It is as if we are players on a small tawdry stage, like players who pretend that all is well, that they are comfortable on their stools in their ill-fitting crowns. But anyone looking to the left or to the right can see that this false court is just a few people perched on a wagon, trying to create an illusion of grandeur.

Margaret visits her brother in the Tower before the court leaves London, and comes back to my rooms looking grave. His lessons have been stopped, his guard has been changed, he has become so silent and so sad that she fears that even if he were to be released tomorrow, he would never recover the spirits of the excited little boy that we brought to the capital. He is nineteen years old now but he is not allowed out into the garden; he is allowed only to walk around the roof of the Tower every afternoon. He says he cannot remember what it is like to run, he thinks he has forgotten how to ride a horse. He is innocent of anything but bearing a great name, and he cannot put that name aside, as Margaret has done, as I and my sisters have done, burying our identities in marriage. It is as if his name as a duke of the House of York will drag him, like a millstone around his neck, down into deep water, and never release him.

“Do you think the king will ever let Edward go?” she asks me. “I don’t dare to ask him, this summer. Not even as a favor. I don’t dare to speak to him. And anyway, Sir Richard has ordered me not to. He says we can say nothing and do nothing that might cause the king to doubt our loyalty.”

“Henry can’t doubt Sir Richard,” I protest. “He has made him chamberlain to Arthur. He’ll send him to govern Wales as soon as it is safe for him to leave court. He trusts him more than anyone else in the world.”

Her quick shake of the head reminds me that the king doubts everybody.

“Is Henry doubting Sir Richard?” I whisper.

“He has set a man to watch us,” she says in an undertone. “But if he can’t trust Sir Richard . . . ?”

“Then I don’t think Teddy will ever be released,” I finish grimly. “I don’t think Henry will ever let him go.”

“No, King Henry won’t . . .” she concedes. “But . . .”

In the silence between us, I can see the unspoken words as clearly as if she had traced them on the wood of the table and then polished them away: “King Henry will never release him: but King Richard would.”

“Who knows what will happen?” I say shortly. “Certainly, even in an empty room, you and I should never, ever speculate.”

We get constant news from Malines. I start to dread seeing the door of the king’s privy chamber close and the guard stand across it with his pike barring the way, for then I know that another messenger or spy has come to see Henry. The king tries to ensure that no news escapes from his constant meetings but quickly word gets out that the Emperor Maximilian has visited his lands in Flanders and the boy, the boy who may not be named, is traveling with him as his dearly beloved fellow monarch. The court in Malines is no longer grand enough for him. Maximilian gives him a great palace in the city of Antwerp, a palace hung with his own standard and decorated with white roses. His name, Richard, Prince of Wales and Duke of York, is emblazoned at the front of the building, his retainers wear the York colors of murrey—a deep berry crimson—and blue, and he is served on bended knee.

Henry comes to me as I am stepping into my barge for an evening on the water. “May I join you?”

It is so rare for him to speak pleasantly these days that I fail to answer him at all, I just gawp at him like a peasant girl. He laughs as if he is carefree. “You seem amazed, that I should want to come for a sail with you.”

“I am amazed,” I say. “But I am very pleased. I thought you were locked in your privy chamber with reports.”

“I was, but then I saw from my window that they were getting your barge ready, and I thought: what a lovely evening it is to be on the water.”

I gesture to my court and a young man bounds out of his seat; everyone else moves along and Henry sits beside me, nodding that the boatmen can cast off.

It is a beautiful evening; the swallows are twisting and turning low over the silvery river, dipping down to snatch a beakful of water and then swirling away. A curlew lifts up from the riverbank and calls low and sweet, its wings wide. Softly, the musicians on the following barge set a note and start to play.

“I am so glad you came with us,” I say quietly.

He takes my hand and kisses it. It is the first gesture of affection between us for many weeks, and it warms me like the evening sunlight. “I am glad too,” he says.

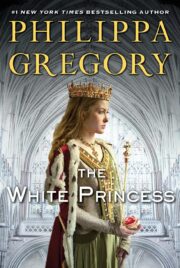

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.