Harry always listens to an appeal to his vanity. Sulkily, he bows his copper head only for a moment, and then he steps to the front of the royal box and lifts his hand to wave at the crowd who bellow their approval. The cheers excite him, he beams and waves again, then he bounces like a young lamb. Beyond him, my son Arthur lifts his hand to wave as well, and smiles. Gently, unseen by the crowd, I get a firm grip of the back of Harry’s jacket and hold him still before he shames all of us by jumping over the low wall altogether.

As the jousters come into the arena I catch my breath. I had expected them to be wearing Tudor green, the eternal Tudor green, the compulsory springtime of my husband’s reign. But he and his mother have ordered them into the colors of York to honor the new little Duke of York, and to remind everyone that the rose of York is here, not in Malines. They are all wearing blue and the deep scarlet murrey of my house, the livery I have not seen since Richard, the last king of York, rode out to his death at Bosworth.

Henry catches the look on my face. “It looks well,” he says indifferently.

“It does,” I agree.

The Tudor presence is stated in the roses which stud the arena, white for York overlaid by the red for Lancaster, and sometimes the new rose which they are growing in greater and greater numbers for occasions like this: the Tudor rose, a red marking inside a white flower, as if every York is actually a Lancaster at heart.

Everyone is invited to the tournament and everyone in England comes: loyalist, traitor, and those very many who have not yet made up their minds. London is filled with people, every lord from every county in England has come with his household, every squire has come with his family, everyone has been commanded to come to celebrate the ennobling of Henry. The palace is filled, there is not a spare inch of floor in the great hall, everyone beds down where they can find a space. The inns for two miles in every direction are bursting at the seams, with four to a bed. All the private houses take in guests, the very stables host men sleeping in the hay barns above the horses. And it is this concentration of so many lords and gentry, citizens, and commoners, this gathering of all the people of England, that makes it so easy, so horribly easy for Henry to arrest everyone he suspects of treason or disloyalty, or even a word out of place.

The moment the joust is over and before anyone can go home, Henry sends out his yeomen of the guard, and men—guilty and innocent alike—are snatched from their lodgings, from their houses, some even from their beds. It is a magnificent attack on everyone whose names Henry has compiled from the time that the boy was first mentioned till now, at the moment that they were most unsuspecting, when they had stepped into Henry’s trap. It is brilliant. It is ruthless. It is cruel.

The lawyers are not alert, most of them have come to the joust as guests, the clerks are still taking their holidays. The accused men can find no one to represent them, they cannot even find their friends to post the massive fines that Henry sets for them. Henry snatches them up quickly, dozens at a time, in a city that has been lulled into carelessness by days of merrymaking into forgetting that they are ruled by a king who is never careless, and hardly ever merry.

THE TOWER OF LONDON, JANUARY 1495

“This is cozy,” he says, warming his hands at the fire.

When I say nothing, he nods at my ladies to leave us and they skitter out of the room, their leather shoes slapping on the stone floors, their skirts sweeping the rushes aside.

“The children are next door,” he says. “I ordered them to be housed there, myself. I know you like them to be near you.”

“And where is Edward of Warwick? My cousin?”

“In his usual rooms,” Henry says with a little grimace at his own embarrassment. “Safe and sound, of course. Safe in our keeping.”

“Why did we not stay at Greenwich? Is there some danger that you’re not telling me about?”

“Oh no, no danger.” He rubs his hands before the fire again and speaks so airily that I am now certain something is badly wrong.

“Then why have we come here?”

He glances to make sure that the door is locked. “One of the boy’s greatest adherents, Sir Robert Clifford, is coming back home to England. He betrayed me, but now he’s coming back to me. He can come here and report to me, thinking to win my favor, and I can arrest him without further trouble. He can go from privy chamber to prison—just down a flight of steps!” He smiles as if it is a great advantage to live in a prison for traitors.

“Sir Robert?” I repeat. “I thought he had betrayed you without possibility of return when he left England? I thought he had run away to be with the boy?”

“He was with the boy!” Henry is exultant. “He was with the boy and the foolish boy trusted him with all his treasure and his plans. But he has brought them all to me. And a sack.”

“A sack?”

Henry nods. He is watching me carefully. “A sack of seals. Everyone who is plotting for the boy in England, everyone who ever sent him a letter closed it under their seal. The boy received the letter and cut the seal from it, he kept the seals, by way of a pledge. And now, Sir Robert brings me the sack of seals. I have every seal. A complete collection, Elizabeth, that identifies everyone who is plotting for the boy against me.”

His face is jubilant, like a rat catcher with a hundred rat tails.

“Do you know how many? Can you guess how many?” I can tell by the tone of his voice that he thinks he is setting a trap for me.

“How many?”

“Hundreds.”

“Hundreds? He has hundreds of supporters?”

“But now I know them all. Do you know the names on the list?”

I have to bite my tongue on my impatience. “Of course I don’t know who wrote to the boy. I don’t know how many seals and I don’t know who they are. I don’t even know if it is a true collection,” I say. “What if it is false? What if there are names on it of men who are faithful to you, who perhaps wrote long ago to Duchess Margaret? What if the boy has sent you this sack on purpose, and Sir Robert is working for him, to fill you with doubt? What if the boy is sowing fear among us?”

I see him catch his breath at a possibility that he had not considered. “Clifford has returned to me—the only one who has returned to me!—and brought me information as good as gold,” he says flatly.

“Or false gold, fool’s gold, that people mistake for the real thing,” I say stoutly. I find my courage and I face him. “Are you saying that any of my kinsmen or -women, or ladies, are on the list?” Not Margaret! I am thinking desperately. Not Margaret. God send that she has had the patience not to rebel against Henry in the hopes of freeing her brother. Please God none of my kinswomen have played their husbands false for love of a boy that they secretly think is my brother? Not my grandmother, not my aunts, not my sisters! Please God that my mother always refused to speak with them, just as she never spoke to me. Please God that no one I love is on Henry’s list and that I shall not see my own kinsmen and -women on the scaffold.

“Come,” he says suddenly.

Obediently, I rise to me feet. “Where?”

“To my presence chamber,” he says, as if it is the most ordinary thing in the world that he should come to my room to fetch me.

“I?”

“Yes.”

“What for?” Suddenly my rooms seem very empty, the door to the children’s schoolroom is shut, my ladies sent away. Suddenly I realize that the Tower is very quiet and the prisons for traitors are just a half a dozen steps away, as Henry reminded me just a moment ago. “What for?”

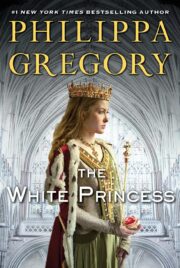

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.