WORCESTER CASTLE, SUMMER 1495

In July I tell him that I have missed my course and am with child again, and he nods silently; even this news cannot bring him joy. He stops coming to my room as a man released from a duty and I am glad to sleep with the companionship of one of my sisters, or with Margaret, who is at court while her husband scours the east of England for hidden traitors. I have lost the desire to lie with my husband, his touch is cold and his hands are bloody. His mother looks at me as if she would call the yeomen of the guard to arrest me for nothing more than my name.

Jasper Tudor is never here at court anymore, but is always riding to get reports from the east coast, where they are certain that the boy will land, from the North, where they think the Scots will invade with the white rose on their banners, or from the west, where Henry’s attempts to crush the Irish has rebounded on him and the people are angrier and more rebellious than ever before.

I spend most of my time in the nursery with my children. Arthur studies with his schoolmasters and every afternoon is ordered out into the tilt yard to master his horse and to learn his skills with lance and sword. Margaret is quick with her lessons and quick in her temper; she will snatch a book from her brothers and run and lock herself in a room before they can shout and chase after her. Elizabeth is as light as a feather, a little baby as pale as snow. They tell me she will fatten up soon, she will be as strong as her brothers and sister, but I don’t believe them. Henry is preparing a betrothal for her, he is desperate to make an alliance with France and will use this little treasure, this child of porcelain, to make a treaty. He will use her as fresh bait to catch the boy. I don’t argue with him. I cannot worry now about her wedding in twelve years’ time, I can only think that this day she has eaten nothing but a little bread and some milk, some fish at dinnertime, no meat at all.

My little boy Henry is bright and willing, quick to learn but easily distracted, a child born for play. He is to go into the Church, and I seem to be the only one who thinks this is ridiculous. My Lady the King’s Mother plans he will be a cardinal like her great friend and ally John Morton. She prays that he will rise through the Church and become a pope, a Tudor pope. It is pointless to tell her that he is a worldly child who loves sport and play and music and food with a most unclerical relish. It does not matter to her. With Arthur as King of England and Henry as Pope in Rome she will have this world and the next in the hands of Tudors and God will have fulfilled the promise he made her when she was a frightened little girl who feared that her son would never rule anything but a couple of castles in Wales and would shortly be driven, by my father, from them.

Her great friend John Morton stays in the south of England, as we spend our summer here in the center of the country, far from the dangerous coast, close to Coventry Castle. Morton is guarding the south coast for My Lady’s fearful son, who goes to and from the court without warning, as if he is riding his own patrols, as if he cannot even trust his spies anymore, but has to see everything for himself. We never know if he will attend dinner, we never know if he will sleep in his own bed; and when his throne is empty the courtiers look around as if for another king who could be seated there. Now the Tudors trust no one but the handful of people who fled with them into exile long ago. Their world has shrunk to the tiny court that hid with them in Brittany; it is as if all the allies and the friends they made, and all the guards and soldiers they recruited after the battle of Bosworth, had never joined them, as if they have no support at all.

It is the court of a frightened pretender and there is no majesty or pride or confidence about it. Working alone, I can do nothing, when I process on my own to dinner with my head held high, smiling around at friends and suspects alike, trying on my own to overcome the impression that the king is afraid and his court are uncertain.

Then, one evening, John Kendal, the Bishop of Worcester, stops me on my way to my rooms with a kindly smile, and asks me, as a man offering to show a rainbow or a pretty sunset: “Have you seen the light from the beacons, Your Grace?”

I hesitate. “Beacons?”

“The sky is quite red.”

I turn to the arrow-slit window in the castle and look out. To the south the sky is quite rosy, and as far as I can see there is a light on a hill, and then another, and then another behind and behind one after another all the way until I can see nothing more.

“What is it?”

“The king commanded beacons to warn him of the landing of Richard of York,” John Kendal says.

“You mean the pretender,” I remind him. “The boy.”

In the glow of the lights I catch his hidden smile and I hear his low laugh. “Of course. I forgot his name. These are the beacons. He must have landed.”

“Landed?”

“These are his beacons. The boy is coming home.”

“The boy is coming home?” I repeat like a fool. It cannot be that I have mistaken the bishop’s delight in the rosy light of the beacons. He is illuminated with joy as if the beacons were welcoming flares to guide ships safely into port. He smiles at me to share his delight that the Plantagenet boy is homeward bound.

“Yes,” he says. “They are lighting his way home at last.”

Next day Henry thunders out of the castle surrounded by his guard, without a word of farewell to me, riding west to raise troops, visiting castles in the Stanley areas, desperate to keep them loyal, uncertain of them all. He does not even say good-bye to the children in the nursery or go to his mother for her blessing. She is horrified by his sudden departure and spends all her time on her knees on the stone floor of the chapel at Worcester, not even coming to breakfast, for she is fasting, starving herself to draw down a blessing on her son. Her thin neck at the top of her gown is red and raw, as she is wearing a hair shirt against her skin to mortify her paper-thin flesh. Jasper Tudor rides beside Henry, like a tired old warhorse that does not know how to stop and rest.

Confused rumors come back to us. The boy has landed in the east of the country, coming into England through Hull and York, as my father did when he returned in triumph from his exile. The boy is following in King Edward’s footsteps as his true son and heir.

Then we hear that the winds blew the boy off course and he has landed in the south of England and there is nobody there to defend the coast but the archbishop and some local bands. What shall prevent the boy from marching on London? There is no one to block the road, there is no one who will deny him.

Henry’s guard rides into the stable yard without warning, and the grooms brush down the exhausted horses and the men stained with mud from the road take the back stairs to their rooms in silence. They don’t shout for ale or boast of their journey, they return to the court like men silent with grim determination, afraid of defeat. Henry dines with the court for two nights, hard-faced, as if he has forgotten all his lessons about being a smiling king. He comes to my rooms to lead me in to dinner and greets me curtly.

“He landed.” He spits out the words as he leads me to the top table. “He got a few men onshore. But he saw the defense and sheered off like a coward. My men killed a few hundred of them, but like fools they let his ship get away. He fled like a boy and they let him go.”

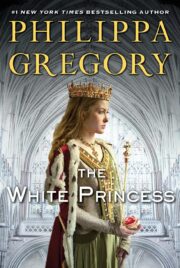

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.