I don’t remind my husband that once he too came to the coast and saw that there was a trap and sailed away without landing. We called him a coward then, too. “So where is he now?”

He looks at me coldly, as if measuring whether it is safe to tell me. “Who knows? Perhaps he’s gone to Ireland? The winds were blowing west, so I doubt he’ll have landed in Wales. Wales at least should be faithful to a Tudor. He’ll know that.”

I say nothing. We both know that he can trust nowhere to be faithful to a Tudor. I hold out my hands and the groom of the ewery pours warm water on my fingers and holds out a scented towel.

Henry rubs his hands and throws the towel at a page boy. “I captured some of his men,” he says with sudden energy. “I have about a hundred and sixty of them, Englishmen and foreigners, all traitors and rebels.”

I don’t need to ask what will happen to the men who sailed with the boy for England. We take our seats and face our court.

“I shall send them round the country and have them hanged in groups in every market town,” Henry says with sudden cold energy. “I shall show people what happens to anyone who turns against me. And I shall try them for piracy—not treason. If I name them as pirates I can kill the foreigners as well. Frenchman and Englishman can hang side by side and everyone will look at their rotting bodies and know that they dare not question my rule no matter where they were born.”

“You won’t forgive them?” I ask, as they pour a glass of wine. “Not any of them? You won’t show mercy? You always say that it is politic to show mercy.”

“Why in hell’s name should I forgive them? They were coming against me, against the King of England. Armed and hoping to overthrow me.”

I bow my head under his fury and know that the court is watching Henry’s rage.

“But the ones that I execute in London will die as pirates do,” he says with sudden harsh relish. His temper vanishes, he beams at me.

I shake my head. “I don’t know what you mean,” I say wearily. “What have you advisors been telling you now?”

“They’ve been telling me how pirates are punished,” he says with a cruel joy. “And this is how I will have these men killed. I will have them tied down by St. Katherine’s Wharf at Wapping. They are traitors and they came against me by sea. I shall find them guilty of piracy and they will be tied down and the tide will come in and slowly, slowly, creep over them, lapping up their feet and their legs till it splashes into their mouths and they will drown inch by inch in a foot of water. D’you think that will teach the people of England what happens to rebels? Do you think that will teach the people of England not to defy me? Never to come against a Tudor?”

“I don’t know,” I say. I am trying to catch my breath as if it is me staked out on the beach with the rising tide splashing against my closed lips, wetting my face, slowly rising. “I hope so.”

Days later, when Henry is gone again on his restless patrolling of the Midlands, we hear that the boy has landed in Ireland and set siege to Waterford Castle. The Irish are flocking to his standard and Henry’s rule in Ireland is utterly overthrown.

I rest in the afternoons; this baby is sitting heavily on my belly and makes me too weary to walk. Margaret sits with me, sewing at my side, and whispers to me that Ireland has become ungovernable, the rule of the English is overthrown, everyone is declaring for the boy. Her husband, Sir Richard, will have to go to that most dangerous island; Henry has commanded him to take troops to fight the boy and his adoring allies. But before Sir Richard has even ordered the ships to transport his troops, the siege is lifted without warning, and the elusive boy is gone.

“Where is he now?” I ask Henry as he prepares to ride out, his yeomen of the guard behind him, armed and helmeted as if they are on campaign, as if he expects an attack on the highways of his own country.

His face is dark. “I don’t know,” he says shortly. “Ireland is a bog of treachery. He is hiding in the wetlands, he is hiding in the mountains. My man in Ireland, Poynings, has no command, he has lost all control, he knows nothing. The boy is like a ghost, we hear of him but we never see him. We know they are hiding him but we don’t know where.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, AUTUMN 1495

Sir Richard Pole has finally sailed for Ireland to try to find Irish chieftains who can be persuaded to hold to their alliance against the boy, and Maggie comes to my rooms every night after dinner and we spend the evening together. We always make sure to keep one of My Lady’s women with us, in earshot, and we always speak of nothing but banalities; but it is a comfort for me to have her by my side. If the lady-in-waiting reports to My Lady, and of course we must assume that she does, she can say that we spent the evening talking of the children, of their education, and of the weather, which is too damp and cold for us to walk with any pleasure.

Maggie is the only one of my ladies that I can talk to without fear. Only to her can I say quietly, “Baby Elizabeth is no stronger. Actually, I think she is weaker today.”

“The new herbs did no good?”

“No good.”

“Perhaps when the spring comes and you can take her into the country?”

“Maggie, I don’t even know that she will see the spring. I look at her, and I look at your little Henry, and though they are so near in age, they look like different beings. She’s like a little faerie child, she is so small and so frail, and he is such a strong stocky boy.”

She puts her hand over mine. “Ah, my dear. Sometimes God takes the most precious children to his own.”

“I named her for my mother, and I fear she will go to her.”

“Then her grandmother will look after her in heaven, if we cannot keep her here on earth. We have to believe that.”

I nod at the words of comfort, but the thought of losing Elizabeth is almost unbearable. Maggie puts her hand on mine.

“We do know that she will live in glory with her grandmother in heaven,” she repeats. “We know this, Elizabeth.”

“But I had such a picture of her as a princess,” I say wonderingly. “I could almost see her. A proud girl, with her father’s copper hair and my mother’s fair skin, and our love of reading. I could almost see her, as if standing for a portrait, with her hand on a book. I could almost see her as a young woman, proud as a queen. And I told My Lady the King’s Mother that Elizabeth would be the greatest Tudor of them all.”

“Perhaps she will be,” Maggie suggests. “Perhaps she will survive. Babies are unpredictable, perhaps she will grow stronger.”

I shake my head on my doubts, and that night, at about midnight, when I am wakened by a deep yellow autumn moon shining through the slats of the shutters, my thoughts go at once to my sick baby. I get up and put on my robe. At once Maggie, sleeping in my bed, is awake. “Are you ill?”

“No. Just troubled. I want to see Elizabeth. You go to sleep.”

“I’ll come with you,” she says, and slips out of bed and throws a shawl over her nightgown.

Together we open the door and the dozing sentry gives a jolt of surprise as if we are a pair of ghosts, white-faced with our hair plaited under our nightcaps. “It’s all right,” Maggie says. “Her Grace is going to the nursery.”

He and his fellow guard follow us as we walk in our bare feet down the cold stone corridor, and then Maggie pauses. “What is it?” she asks.

“I thought I heard something,” I say quietly. “Can you hear it? Like singing?”

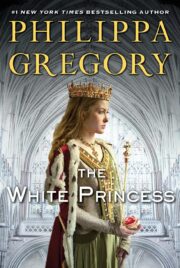

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.