She shakes her head. “Nothing. I can’t hear anything.”

I know what the sound is then, and I turn to the nursery in sudden urgency. I quicken my stride, I start to run, I push my way past the guard and race up the stone steps to the tower, where the nursery is warm and safe at the top. As I open the door the nurse starts up from where she is bending over the little crib, her face aghast, saying: “Your Grace! I was just going to send for you!”

I snatch up Elizabeth into my arms and she is warm and breathing quietly but white, fatally white, and her eyelids and her lips as blue as cornflowers. I kiss her for the last time and I see her fleeting tiny smile, for she knows I am here, and then I hold her, I don’t move at all, I just stand and hold her to my heart as I feel the little chest rise and fall, rise and fall, and then become still.

“Is she asleep?” Maggie asks hopefully.

I shake my head and I feel the tears running down my face. “No. She’s not asleep. She’s not asleep.”

In the morning, after I have washed her little body and dressed her in her nightgown, I send a short message to her father to tell him that our little daughter is dead. He comes home so quickly that I guess he had the news ahead of my letter. He has a spy set on me, as he has on everyone else in England, and that they have already told him that I ran from my bedchamber in the middle of the night to hold my daughter in my arms as she died.

He comes into my rooms in a rush and kneels before me, as I am seated, dressed in dark blue, in my chair by my fireside. His head is bowed as he reaches blindly for me. “My love,” he says quietly.

I take his hands and I can hear, but I don’t see, my ladies skitter out of the room to leave us alone. “I am so sorry I was not here,” he says. “God forgive me that I was not with you.”

“You’re never here,” I say softly. “Nothing matters to you anymore but the boy.”

“I am trying to defend the inheritance for all our children.” He raises his head but speaks without any anger. “I was trying to make her safe in her own country. Oh, dear child, poor little child. I didn’t realize she was so ill, I should have listened to you. God forgive me that I did not.”

“She wasn’t really ill,” I say. “She just never thrived. When she died it wasn’t a struggle at all, it was as if she just sighed, and then she was gone.”

He bows his head and puts his face against my hands in my lap. I can feel a hot tear on my fingers, and I bend over him and hold him tightly, I grip him as if I would feel his strength and have him feel mine.

“God bless her,” he says. “And forgive me for being away. I feel her loss more than you know, more than I can tell you. I know it seems that I’m not a good father to our children, and I’m not a good husband to you—but I care for them and for you more than you know, Elizabeth. I swear that at least I will be a good king for them. I will keep the kingdom for my children and your throne for you, and you will see your son Arthur inherit.”

“Hush,” I say. With the memory of Elizabeth, warm and limp in my arms, I don’t want to tempt fate by foretelling the future of our other children.

He gets up and I stand with him as he wraps his arms around me and holds me tightly, his face against my neck as if he would inhale comfort from the scent of my skin.

“Forgive me,” he breathes. “I can hardly ask it of you; but I do. Forgive me, Elizabeth.”

“You are a good husband, Henry,” I reassure him. “And a good father. I know that you love us in your heart, I know that you wouldn’t have gone away if you had thought we might lose her, and see, here you are—home almost before I had sent for you.”

He tips his head back to look at me, but he does not deny that it was his spies who told me that his daughter was dead. He did not hear it first from me. “I have to know everything,” is all he says. “That’s how I keep us safe.”

My Lady the King’s Mother plans and executes a great funeral for our little girl. She is buried as a princess in the chapel of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey. Archbishop Morton performs the funeral service, the Bishop of Worcester, who told me that the boy was coming home, serves the Mass with quiet dignity. I cannot tell Henry that the bishop was smiling the night that the beacons were lit for the landing of the boy. I cannot report on the priest who is burying my child. I fold my hands before me and I rest my head against them and I pray for her precious soul and I know without doubt that she is in heaven; and that I am left to the bitterness of a loss on earth.

Arthur, my firstborn and always the most thoughtful of my children, puts his hand in mine, though he is now a big boy of just nine. “Don’t cry, Lady Mother,” he whispers. “You know she’s with our lady grandmother, you know she has gone to God.”

“I know,” I say, blinking.

“And you’ve still got me.”

I swallow my tears. “I still have you,” I agree.

“You’ll always have me.”

“I’m glad of that.” I smile down at him. “I am so glad of that, Arthur.”

“And perhaps the next baby will be a girl.”

I hold him close to me. “Whether she is a girl or a boy, she can’t take the place of Elizabeth. Do you think if I lost you, I wouldn’t mind because I still had Harry?”

His own eyes are bright with tears but he laughs at that. “No, though Harry would think so. Harry would think it a very good exchange.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, NOVEMBER 1495

I turn to my maid-in-waiting. “Please fetch the dark purple ribbon from the wardrobe rooms,” I say.

She curtseys. “I’m sorry, Your Grace, I thought you wanted the blue.”

“I did, but I have changed my mind. And Claire—go with her and bring the matching purple cloak.”

The two of them leave as Margaret opens the box of jewels and holds up my amethysts as if to show me. The other women are closer to the fireside, and can see us but not hear what we are saying. Margaret holds the jewels to the light to make them sparkle with a deep purple fire.

“What?” I ask tersely as I seat myself before my looking-glass.

“He’s in Scotland.”

A little bubble of laughter, or perhaps it is a sob of fear, forms in my throat. “In Scotland? He’s left Ireland? You are sure?”

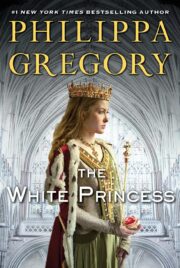

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.