“Honored guest of King James. The king acknowledges him, is holding a great meeting of the lords, calls him by his title: Richard Duke of York.” She stands behind me, lifting up the amethyst coronal to show me.

“How d’you know?”

“My husband, God bless him, told me. He got it from the Spanish ambassador, who got it from the Spain dispatches—everything that they write to Spain they send a copy to us, the alliance between the king and the Spanish has grown so strong.” She checks that the women at the fire are engaged in their own conversation, puts the amethysts around my neck, and goes on. “The Spanish ambassador to Scotland was called in by King James of Scotland, who raged at him and said that our King Henry was a cat’s-paw in the hands of the Spanish king and queen. But he—James—would see the rightful king of England take his throne.”

“Is he going to invade?”

Margaret puts the coronal on my head. I see my wondering face in the looking-glass before me, my eyes wide, my face pale. For a moment I seem like my mother, for a moment I am a beauty as she was. I pat my white cheeks. “I look like I have seen a ghost.”

“We all look like that,” Margaret says, a weak reflected smile over my head as she fastens the amethysts around my neck. “We are all going around as if a ghost is on his way to us. They are singing in the streets about the Duke of York, who dances in Ireland and plays in Scotland and will walk in an English garden and everyone will be merry again. They say he is a ghost come to dance, a duke brought back from the dead.”

“They say it is my brother,” I say flatly.

“The King of Scotland says that he will put his life on it.”

“And what does your husband say?”

“He says there will be war,” she replies, the smile fading from her face. “The Scots will invade to support Richard, they will invade England, and there will be war.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, CHRISTMAS 1495

My aunt Katherine, always a dutiful wife, puts him to bed in their rich and comfortable rooms, calls physicians, apothecaries, and nurses to care for him, but she is elbowed aside by My Lady the King’s Mother, who prides herself on her knowledge of medicine and herbs and says that Jasper’s constitution is so strong that all he needs is good food, rest, and some tinctures of her own creation to get well. My husband Henry visits the sickroom three times a day, in the morning to see how his uncle has slept, before dinner to make sure that he has the very best that the kitchen can offer and that it is served to him first, hot and fresh, on bended knee, and then last thing at night, before he and his mother go to the chapel and pray for the health of the man who has been the keystone of their lives for so very long. Jasper has been like a father to Henry, and his only constant companion. He has been his protector and his mentor. Henry would have died without his uncle’s constant loving care. To My Lady, I think he has been the most potent of influences a woman can know: the love she never named, the life she never led, the man she should have married.

Both Henry and his mother share a confident assumption that Jasper, who has always ridden hard and fought hard, who has always escaped danger and thrived in exile, will once again slide through the claws of death and dance at the Christmas feast. But after a few days they look more and more grave, and after a few more they are calling on the physicians to come and see him. A few days more, and Jasper insists on seeing a lawyer and making his will.

“His will?” I repeat to Henry.

“Of course,” he snaps. “He is a man of sixty-three. And devout, and responsible. Of course he is making his will.”

“He is very ill then?”

“What do you think?” He rounds on me. “Did you think that he had taken to his bed for the pleasure of a rest? He has never rested in his life; he has never been away from my side when I needed him; he has never spared himself, not for one day, not for one moment . . .” He breaks off and turns away from me so that I cannot see the tears in his eyes.

Gently, I go behind him, as he is seated in his chair, and put my arm around his back to hold him tightly; I lean down and rest my cheek against his for comfort. “I know how much you love him,” I say. “He has been like a father and more for you.”

“He has been my protector, and my teacher, my mentor and my friend,” he says brokenly. “He took me from England to safety and endured exile for my sake when I was only a boy. Then he brought me back to claim the throne. I wouldn’t even have made it to the battlefield without him. I couldn’t have found my way across England, I wouldn’t have dared to trust the Stanleys, God knows I wouldn’t have won the battle but for his teaching. I owe him everything.”

“Is there anything I can do?” I ask helplessly, for I know there will be nothing.

“My mother is doing everything,” Henry says proudly. “In your condition you can do nothing to help her. You can pray if you like.”

Ostentatiously, I take my ladies to chapel and we pray and command a sung Mass for the health of Jasper Tudor, uncle to the King of England, old irrepressible rebel that he is. Christmas comes to court but Henry commands that it be celebrated quietly; there is to be no loud music and no shouts of laughter to disturb the sickroom where Jasper lies sleeping, and the king and his mother keep their constant vigil.

Arthur is taken in to see his dying uncle, Harry goes in after him. Little Princess Margaret is spared the ordeal but My Lady insists that the boys kneel at the bedside of the greatest Englishman the world has ever known.

“Welshman,” I say quietly.

On Christmas Day we go to church and celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ and pray for the health of his most beloved son and soldier Jasper Tudor. But on the day after, Henry comes to my room unannounced early in the morning and sits on the foot of my bed as I sleepily rise up, and Cecily, who is sleeping with me, jumps up, curtseys, and scuttles out of the room.

“He’s gone,” Henry says. He does not sound grieved so much as amazed. “My Lady Mother and I were sitting with him and he stretched out his hand to her and he smiled at me, and then he lay back on his pillows and breathed out a long sigh—and then he was gone.”

There is a silence. The depth of his loss is so great that I know I can say nothing to comfort him. Henry has lost the only father he ever knew; he is as bereft as an orphan child. Clumsily, I get to my knees, my big belly making me awkward, and I stretch my arms out towards him to hold him. He has his back to me and he does not turn, he does not realize I am reaching out to him in pity. He is all alone.

For a moment I think he is absorbed in grief, but then I realize that the loss of Jasper only adds to his perennial fears.

“So who is going to lead my army against the boy and the Scots?” Henry asks, speaking to himself, cold with fear. “I am going to have to face the boy in battle, in the North of England, where they hate me. Who is going to command if Jasper has left me? Who will be at my side, who can I trust, now that my uncle is dead?”

PALACE OF SHEEN, RICHMOND, WINTER 1496

I wait till the end of a chapter and for the girl to turn the manuscript page, and I say, “I will walk in the garden.”

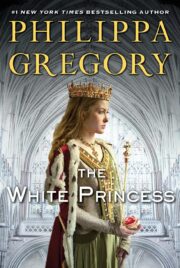

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.