Now I am sorry that I told Henry how my father used to look over the heads of the people reading the loyal address and calculate how much they could pay. My father’s system of loans and fines and borrowings has become Henry’s hated tax system and everywhere we go, we are followed by clerks who count the glass windows in the houses, or the flocks of sheep in the meadows, or the crops in the fields, and present the people who come to see us with a demand for payment.

Instead of being greeted by people cheering in the streets, crowding to wave at the royal children and blow kisses to me, the people are out of sight, bundling their goods into warehouses, smuggling away their account books, denying their prosperity. Our hosts serve the meanest of feasts and hide away their best tapestries and silverware. Nobody dares show the king hospitality and generosity, for either he or his mother will claim it as evidence that they are richer than they pretend, and accuse them of failing to declare their wealth. We go from one great house and abbey to another like grasping tinkers who visit only to steal, and I dread the apprehensive faces that greet us and their looks of relief when we leave.

And everywhere we go, at every stop, there are hooded men, following us like the figure of Death itself, on foundering horses, who speak to my husband in secret and sleep the night and then ride out the next day on the best mounts in the stables. They head west, where the Cornishmen, landowners, miners, sailors, and fishermen are declaring that they will not pay another penny of the Tudor tax, or they ride east, where the coast lies dangerously open to an invasion, or they go north to Scotland, where we hear that the king is building an army and casting guns the like of which have never been seen before, for his beloved cousin: the boy who would be King of England.

“At last I have him.” Henry walks into my room, ignoring my ladies, who leap to their feet and drop into low curtseys, ignoring the musicians, who trail into silence and wait for an order. “I have him. Look at that.”

Obediently I look at the page he shows me. It is a mass of symbols and numbers, saying nothing that I can understand.

“I can’t read this,” I tell him quietly. “This is the language you use: spies’ language.”

He tuts with impatience and draws another sheet of paper from under the first. It is a translation of the code from the Portuguese herald, sealed by the King of France himself to prove that it is true. The so-called Duke of York is the son of a barber in Tournai and I have found his parents and can send them to you . . .

“What do you think of that?” Henry demands of me. “I can prove that the boy is an imposter. I can bring his mother and father to England and they can declare him the son of a barber in Tournai. What do you think?”

I sense Margaret, my cousin, taking a few steps closer to me, as if she would defend me from the rising volume of Henry’s voice. The more uncertain he is, the more he blusters. I rise to my feet and I take his hand in my own.

“I think that it proves your case completely,” I say, just as I would soothe my son Harry, if he were arguing with his brother, near to tears with frustration. “I am sure that this will make your case completely.”

“It does!” he asserts furiously. “It is as I said—he is a poor boy from nowhere.”

“It is just as you said,” I repeat. I look up at his flushed angry face and I feel nothing but pity for him. “This proves that you are completely right.”

A little shudder goes through him. “I shall send for them, then,” he says. “These lowborn parents. I shall bring them to England and everyone can see the lowly parentage of this false boy.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, AUTUMN 1496

It is such a ludicrous proposal that when Henry goes on looking for a bereft mother, for a missing boy, for anything—a name if nothing else—that I see it as the measure not of his determination to unravel a mystery, but of his increasing desperation to create an identity for the boy and pin a name on him. When I suggest that really anyone would do, it does not have to be a Tournai barber—he might as well seek anyone who is prepared to say that the boy was born and raised by them, and then went missing—Henry scowls at me and says: “Exactly, exactly. I could have half a dozen parents and still no one would believe that I have found the right ones.”

One evening in autumn I am invited into the queen’s rooms—they are still called the queen’s rooms—by My Lady the King’s Mother, who tells me that she needs to talk with me before dinner. I go with Cecily my sister, as Anne is in her confinement, expecting her first child; but when the great double doors are thrown open I see that My Lady’s presence chamber is empty, and I leave Cecily to wait for me there, beside the economical fire of small off-cut timbers, and I go into My Lady’s privy chamber alone.

She is kneeling before a prie-dieu; but when I come in, she glances over her shoulder, whispers “Amen,” and then rises to her feet. We both curtsey, she to me as I am queen, I to her as she is my mother-in-law; we press cool cheeks against each other as if we were exchanging a kiss, but our lips never touch the other’s face.

She gestures towards a chair that is the same height as hers, on the other side of the fireplace, and we sit simultaneously, neither one of us taking precedence. I am beginning to wonder what all this is about.

“I wish to speak to you in confidence,” she begins. “In absolute confidence. What you tell me will not go beyond the walls of this room. You can trust me with anything. I give you my sacred word of honor.”

I wait. I very much doubt that I am going to tell her anything, so she need not assure me that she will not repeat it. Besides, anything that might be of use to her son, she would repeat to him in the next moment. Her sacred word of honor would not even cause a second’s delay. Her sacred word of honor is worth nothing against her devotion to her son.

“I want to speak of long-ago days,” she says. “You were just a little girl and none of it was your fault. No blame is attached to you by me or anyone. Not by my son. Your mother commanded everything, and you were obedient to her then.” She pauses. “You do not have to be obedient to her now.”

I bow my head.

My Lady seems to have trouble in starting her question. She pauses, she taps her fingers on the carved arm of her chair. She closes her eyes as if in brief prayer. “When you were a young woman in sanctuary, your brother the king was in the Tower, but your little brother Richard was still with you in hiding. Your mother had kept him by her side. When they promised her that your brother Edward was to be crowned they demanded that she send Prince Richard into the Tower, to join his brother, to keep him company. Do you remember?”

“I remember,” I say. Despite myself I glance towards the heaped logs in the fireplace as if I could see in the glowing embers the arched roof of the sanctuary, my mother’s white desperate face, the dark blue of her mourning gown, and the little boy that we bought from his parents, took hold of, washed, commanded to say nothing, and dressed up as my little brother, hat pulled low on his head, a muffler across his mouth. We handed him over to the archbishop, who swore he would be safe, though we did not trust him, we did not trust any of them. We sent that little boy into danger, to save Richard. We thought it would buy us a night, perhaps a night and a day. We could not believe our luck when no one challenged him, when the two boys together, my brother Edward and the pauper child, kept up the deception.

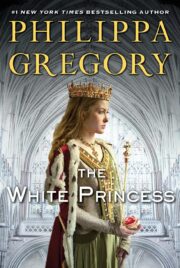

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.