“The lords of the privy council came and demanded that you hand your little brother over to them,” My Lady says, her voice a lilting murmur. “But now, I wonder if you did?”

I look at her, meeting her gaze with an honest frank stare. “Of course we did,” I say bluntly. “Everyone knows that we did. The whole privy council witnessed it. Your own husband Thomas, Lord Stanley, was there. Everyone knows that they took my little brother Richard to live with my brother the king, in the Tower, to keep him company before his coronation. You were at court yourself, you must have seen them take him to the Tower. You must remember, everybody knew, that my mother wept as she said good-bye to him, but the archbishop himself swore that Richard would be safe.”

She nods. “Ah, but then . . . then, did your mother lay a little plot to get them out?” My lady draws closer, her hand reaching out like a claw clasping my hands in my lap. “She was a clever woman, and always alert to danger. I wonder if she was ready for them to come for Prince Richard? Remember, I joined my men with hers in an attack on the Tower to rescue them. I tried to save them too. But after that, after it failed, did she save them—or perhaps just save Richard? Her youngest boy? Did she have a plot that she did not tell me about? I was punished for helping her, I was imprisoned in my husband’s house and forbidden from speaking or writing to anyone. Did your mother, loyal and clever woman that she was, did she get Richard out? Did she get your brother Richard out of the Tower?”

“You know that she was plotting all the time,” I say. “She was writing to you, she was writing to your son. You would know more than I do about that time. Did she tell you she had him safe? Have you kept that secret, all this long time?”

She whips back her hand as if I were as hot as the embers in the hearth. “What d’you mean? No! She never told me such a thing!”

“You were plotting with her to free us, weren’t you?” I ask, as sweet as sugared milk. “You were plotting with her to bring in your son to save us? That was why Henry came to England? To free us all? Not to take the throne, but to restore it to my brother and to free us?”

“But she didn’t tell me anything,” Lady Margaret bursts out. “She never told me anything. And though everyone said that the boys were dead, she never held a Requiem Mass for them, and we never found their bodies, we never found their murderers nor any trace or whisper of a plot to kill them. She never named their killers and no one ever confessed.”

“You hoped that people would think it was their uncle Richard,” I observed quietly. “But you didn’t have the courage to accuse him. Not even when he was dead in an unmarked grave. Not even when you publicly listed his crimes. You never accused him of that. Not even Henry, not even you had the gall to say that he murdered his nephews.”

“Were they murdered?” she hisses at me. “If it was not Richard? It doesn’t matter who did it! Were they murdered? Were they both killed? Do you know that?”

I shake my head.

“Where are the boys?” she whispers, her voice barely louder than the flicker of flame in the hearth. “Where are they? Where is Prince Richard now?”

“I think you know better than me. I think you know exactly where he is.” I turn back to her, and I let her see my smile. “Don’t you think it is him, in Scotland? Don’t you think he is free, and leading an army against us? Against your own son—calling him a usurper?”

The anguish in her face is genuine. “They’ve crossed the border,” she whispers. “They’ve mustered a massive force, the King of Scotland rides with the boy at the head of thousands of men, he’s cast cannon, bombards, he’s organized them—no one has seen such an army in the North before. And the boy has sent a proclamation . . .” She breaks off, and from inside her gown she draws it out. I cannot deny my curiosity; I put out my hand and she passes it over. It is a proclamation by the boy, he must have had hundreds made, but at the bottom is his signature, RR—Ricardus Rex, King Richard IV of England.

I cannot take my eyes from the confident swirl of the initial. I put my finger on the dry ink; perhaps this is my brother’s signature. I cannot believe that my fingertip will not sense his touch, that the ink will not grow warm under my hand. He signed this, and now my finger is on it. “Richard,” I say wonderingly, and I can hear the love in my voice. “Richard.”

“He calls upon the people of England to capture Henry as he flees,” Henry’s mother says, her voice quavering. I hardly hear her, I am thinking of my little brother, signing hundreds of proclamations Ricardus Rex: Richard the King. I find I am smiling, thinking of the little boy that my mother loved so much, that we all loved for his sunny good nature. I think of him signing this flourish and smiling his smile, certain that he will win England back for the House of York.

“He has crossed the Scottish border, he is marching on Berwick,” she moans.

At last I realize what she is saying. “They have invaded?”

She nods.

“The king is going to go? He has his troops ready?”

“We’ve sent money,” she says. “A fortune. He is pouring money and arms into the North.”

“He is riding out? Henry will lead his army against the boy?”

She shakes her head. “We won’t put an army in the field. Not yet, not in the North.”

I am bewildered. I look from the bold proclamation in black ink to her old, frightened face. “Why not? He must defend the North. I thought you were ready for this?”

“We can’t!” she bursts out. “We dare not march an army north to face the boy. What if the troops turn on us as soon as we get there? If they change sides, if the men declare for Richard, then we will have done nothing but give him an army and all our weapons. We dare not take a mustered army anywhere near him. England has to be defended by the men of the North, fighting under their own leaders, defending their own lands against the Scots, and we will hire mercenaries to bolster their ranks—men from Lorraine and from Germany.”

I look at her incredulously. “You are hiring foreign soldiers because you can’t trust Englishmen?”

She wrings her hands. “People are so bitter about the taxation and the fines, they speak against the king. People are so untrustworthy, and we can’t be sure . . .”

“You can’t trust an English army not to change sides and fight against the king?”

She hides her face in her hands; she sinks into her chair, almost sinking to her knees as if in prayer. I look at her blankly, unable to conjure an expression of sympathy. I have never in my life heard of such a thing as this: a country invaded and the king afraid to march out to defend his borders, a king who cannot trust the army he has mustered, equipped, and paid. A king who looks like a usurper and calls on foreign troops even as a boy, an unblooded boy, demands his throne.

“Who will lead this northern army if the king won’t go?” I ask.

This alone gives her some joy. “Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey,” she says. “We are trusting him with this. Your sister is bearing his child in our keeping, I am certain he won’t betray us. And we have her and his first child as a hostage. The Courtenays will stand by us, and we will marry your sister Catherine to William Courtenay, to make them hold firm. And to have a man who was known to be loyal to the House of York riding against the boy will look good, don’t you think? It must make people stop and think, won’t it? They must see that we kept Thomas Howard in the Tower and he came out safely.”

“Unlike the boy,” I remark.

Her eyes snap towards me and I see terror in her face. “Which boy?” she asks. “Which boy?”

“My cousin, Edward,” I say smoothly. “You still hold him for no reason, without charge, unjustly. He should be released now, so that people cannot say that you take boys of York and hold them in the Tower.”

“We don’t.” She answers by rote as if it is the murmured response to a prayer that she has learned by heart. “He is there for his own safety.”

“I ask for his release,” I say. “The country thinks he should be freed. I, as queen, request it. At this moment, where we should show that we are confident.”

She shakes her head and sits back in her chair, firm in her determination. “Not until it is safe for him to come out.”

I rise to my feet, the proclamation still in my hand that calls for the people to rise against Henry, refuse his taxation, capture him as he flees back to Brittany where he came from. “I can’t comfort you,” I say coldly. “You have encouraged your son to tax people to the point of their ruin, you have allowed him to hide himself away and not go out and show himself and make friends, you have encouraged him to pursue and persecute this boy who now invades us, and you have urged him to recruit an army that he cannot trust, and now to bring in foreign soldiers. Last time he brought in foreign soldiers they brought the sweat, which nearly killed us all. The King of England should be beloved by his people, not an enemy to their peace. He should not be afraid of his own army.”

“But is the boy your brother?” she demands hoarsely. “That’s what I called you here to answer. You know. You must know what your mother did to save him. Is your mother’s favorite boy coming against mine?”

“It doesn’t matter,” I say, suddenly seeing my way clear and away from this haunting question. I have a sudden lift of my spirits as I understand, at last, what I should answer. “It doesn’t matter who Henry is facing. Whether it is my mother’s favorite boy or another mother’s son. What matters is that you have not made your boy the beloved of England. You should have made him beloved and you have not done so. His only safety lies in the love of his people, and you have not secured that for him.”

“How could I?” she demands. “How could such a thing ever be done? These are faithless people, these are a heartless people, they run after will-o’-the-wisps, they don’t value true worth.”

I look at her and I almost pity her, as she sits twisted in her chair, her glorious prie-dieu with its huge Bible and the richly enameled cover behind her, the best rooms in the palace draped with the finest tapestries and a fortune in her strongbox. “You could not make a beloved king, for your boy was not a beloved child,” I say, and it is as if I am condemning her. I feel as hard-hearted, as hard-faced, as the recording angel at the end of days. “You have tried for him, but you have failed him. He was never loved as a child, and he has grown into a man who cannot inspire love nor give love. You have spoiled him utterly.”

“I loved him!” She leaps up suddenly furious, her dark eyes blazing with rage. “Nobody can deny that I loved him! I have given my life for him! I only ever thought of him! I nearly died giving birth to him and I have sacrificed everything—love, safety, a husband of my choice—just for him.”

“He was raised by another woman, Lady Herbert, the wife of his guardian, and he loved her,” I say relentlessly. “You called her your enemy, and you took him from her and put him in the care of his uncle. When you were defeated by my father, Jasper took him away from everything he knew, into exile, and you let them go without you. You sent him away, and he knew that. It was for your ambition; he knows that. He knows no lullabies, he knows no bedtime stories, he knows no little games that a mother plays with her sons. He has no trust, he has no tenderness. You worked for him, yes, and you plotted for him and you strove for him—but I doubt that you ever, in all his baby years, held him on your knees and tickled his toes, and made him giggle.”

She shrinks back from me as if I am cursing her. “I am his mother, not his wet nurse. Why would I caress him? I taught him to be a leader, not a baby.”

“You are his commander,” I say. “His ally. But there is no true love in it—none at all. And now you see the price you pay for that. There is no true love in him, neither to give nor receive—none at all.”

Horrifying stories come from the North, of the Scots army coming in like an army of wolves, destroying everything they find. The defenders of the North of England march bravely against them, but before they can join battle, the Scots have melted away, back to their own high hills. It is not a defeat, it is something far worse than that: it is a disappearance. It is a warning which only tells us that they will come again. So Henry is not reassured, and demands money from Parliament—hundreds of thousands of pounds—and raises more in reluctant loans from all his lords and from the merchants of London to pay for men to be armed and stand ready against this invisible threat. Nobody knows what the Scots are planning, if they will raid constantly, destroying our pride and our confidence in the North of England, coming out of the blizzards at the worst time of year; or if they will wait for spring and launch a full invasion.

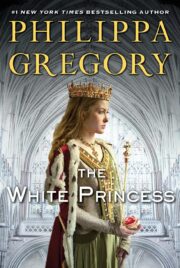

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.