The rebels come on, nearing London, growing in numbers. They are led by Lord Audley, and we know that other lords must be sending them arms, money, and men. I hear nothing from Henry, I have to trust that he is mustering his men, preparing a force and readying himself to march against them. I have no word from him and he does not write to his mother either, though she spends her days on her knees in the chapel that blazes, night and day, with the light of the votive candles that she has lit for him.

My son Arthur, in the Tower for safety with us, comes to me. “Is my father blocking the rebels’ march?” he asks me.

“I am sure,” I say, though I am not sure.

In his rooms Edward, my cousin, must hear the marching feet, the shouted orders, the changing of the guard at four-hourly intervals. Maggie, who joins me as her husband rides out with mine, is the only one of us who is allowed to see him. She comes to me with her face grave.

“He’s very quiet,” is all she says. “He asked me why we were all here, he knows we are all here in the Tower, and why there was so much noise. When I said that there were rebels marching on London all the way from Cornwall he said—” She breaks off and puts her hand over her mouth.

“What?” I ask. “What did he say?”

“He said that there was not much to come to London for, it is a very dull place. He said someone should tell them that there is no company in London at all, and it is lonely. It’s very, very lonely.”

I am horrified. “Maggie, has he lost his wits?”

She shakes her head. “No, I’m sure not. It’s just that he has been kept alone for so very long, he has almost forgotten how to speak. He is like a child who has had no childhood. Elizabeth—I have failed him. I have failed him so badly.”

I go to embrace her, but she turns away from me and drops a curtsey. “Let me go to my room and wash my face,” she says. “I can’t speak of him. I can’t bear to think of him. I have changed my name and denied my family and left him behind. I have snatched my own freedom and left him in here, like a little bird in a cage, like a blinded songbird.”

“When this is over . . .”

“When this is over it will be even worse!” she exclaims passionately. “All this time we have been waiting for the king to feel safe on his throne; but he never feels safe. When this is over, even if we triumph, the king will still have to face the Scots. He may have to face the boy. The king’s enemies come one after another, he makes no friends and he has new enemies every year. It is never safe enough for him to release my brother. He will never be safe on the throne.”

I clap my hand over her trembling mouth. “Hush, Maggie. Hush. You know better than to talk like this.”

She drops a curtsey and goes from my rooms and I don’t detain her. I know she speaks nothing but the truth and that these battles, between these ill-armed desperate men from the west, the war in the North between the Scots and the English, the mustering rebels in Ireland, and the conflict to come between the boy and the king, will give us a summer of bloodshed and an autumn of reckoning, and nobody can tell what the count will be, or who will be the judge or the victor.

The panic starts at dawn. I can hear the shouted commands and the noise of running feet as the commander of the watch calls out the troops. The tocsin starts to sound a warning and then all the bells through the City of London and beyond, all the bells of England, start to sound as the alarm is given that the Cornishmen have come and now they are not demanding that taxes be forgiven and the king’s false advisors dismissed, now they are demanding that the king be thrown down.

Lady Margaret, the king’s mother, comes out of the chapel, blinking like a frightened owl at the dawn light, and at the uproar inside the Tower. She sees me at the entrance to the White Tower and hurries across the green towards me. “You stay here,” she says harshly. “You’re commanded to stay here for your own safety. Henry said that you were not to leave. You and the children are to stay here.”

She turns towards one of the commanders of the guard, and I realize that she will give the order for my arrest if she thinks for a moment that I am hoping to escape.

“Are you mad?” I suddenly demand bitterly. “I am Queen of England, I am the king’s wife and mother of the Prince of Wales! Of course I am staying here in this, my home city, among my people. Whatever happens I would not leave. Where do you think I would go? I am not the one that spent my life in exile! I did not come in at the head of an army, speaking a foreign language! I am English born and English bred. Of course I am going to stay in London. These are my people, this is my country. Even if they carry arms against me they are still my people and this is still where I belong!”

She wavers in the face of my unexpected fury. “I don’t know, I don’t know,” she says. “Don’t be angry, Elizabeth. I am only trying to keep us all safe. I don’t know anything, anymore. Where are the rebels?”

“Blackheath,” I say shortly. “But they have lost a lot of men. They went into Kent and there was a skirmish.”

“Are they opening the city gates to them?” she asks. We can both hear the uproar in the streets. She clutches hold of my arm. “Are the citizens and their militia going to let them into London? Are they going to betray us?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “Let’s go up on the walls where we can see what’s happening.”

My Lady, my sisters, Maggie, Arthur and the younger children, and I all go up the narrow stone steps to the perimeter walls of the Tower. We look south and east, to where the river winds out of sight, and we know that, not far away, only seven miles, the Cornish rebels are triumphantly occupying Blackheath, outside our palace of Greenwich, and setting up camp.

“My mother once stood here,” I tell my children. “She was here under siege, just like this, and I was with her, just a little girl.”

“Were you frightened?” six-year-old Henry asks me.

I hug him, and smile to feel him pull away from me. He is eager to stand on his own two feet, he wants to look independent, ready for battle. “No,” I say. “I wasn’t frightened. For I knew that my uncle Anthony would protect us, and I knew that the people of England would never hurt us.”

“I will protect you now,” Arthur promises. “If they come, they will find us ready. I am not afraid.”

At my side, I feel My Lady shrink back. She has no such certainties.

We walk around the walls to the north side, so that we can look down into the streets of the City. The young apprentices are running from house to house, banging on doors and holloaing to summon men to defend the city gates, borrowing weapons from dusty old cupboards, calling for old pikes to be brought out of the cellars. The trained military bands are running down the streets, ready to defend the walls.

“See?” Arthur points them out.

“They’re for us,” I observe to My Lady the King’s Mother. “They’re arming against the rebels. They’re running to the city gates to close them.”

She looks doubtful. I know that she fears that they will throw open the gates as soon as they hear the rebels cry that they will abolish taxes. “Well, anyway, we’re safe in here,” I say. “The Tower gates are shut, the portcullis is down, and we have cannon.”

“And Henry will be coming with his army to rescue us,” My Lady asserts.

Margaret, my cousin, exchanges a quick skeptical look with me. “I am sure he will,” I reply.

In the end it is Lord Daubney, not Henry, who falls on the exhausted Cornishmen as they are resting after their long march from the west. The cavalry go through the sleeping men slashing and hacking as if they were practicing sword thrusts in a hayfield. Some of them carry a mace—a great swinging ball that can knock a man’s head clean from his shoulders, or smash his face into a pulp, even inside a metal helmet. Some of them carry lances and stab and thrust as they go, or battle-axes with a terrible spike at one end that can punch through metal. Henry has planned the battle and put cavalry and archers on the other side of the rebel army so there is no escape for them. The Cornishmen, armed with little more than staves and pitchforks, are like the sheep of their own thin-earth moorland, herded this way and that, rushing in terror trying to get out of the way, hearing the whistle of thousands of arrows, running from the cavalry only to find the infantry, armed with pikes and handguns, stolidly advancing towards them, deaf to all calls of brotherhood.

They beat the Cornishmen to their knees, they go facedown in the mud before they drop their weapons, raise their hands, and offer their surrender. An Gof, their leader, breaks away from the battle and runs for his life, but is ridden down like a leggy broken-winded stag after a long chase. Lord Audley the rebel leader offers his sword to his friend Lord Daubney, who accepts it grim-faced. Neither lord is quite sure if he has been fighting on the right side; it is a most uncertain surrender, in a most ignoble victory.

“We’re safe,” I tell the children, when the scouts come to the Tower to tell us that it is all over. “Your father’s army has beaten the bad men and they are going back to their homes.”

“I wish I had led the army!” Henry says. “I should have fought with a mace. Bash! Swing and bash!” He dances around the room miming holding the reins of a galloping horse with one hand and swinging a mace with his other little fist.

“Perhaps when you are older,” I say to him. “But I hope that we will be at peace now. They will go back to their homes and we can go back to ours.”

Arthur waits for the younger children to be distracted and then he comes to my side. “They’re building gallows at Smithfield,” he says quietly. “An awful lot of them won’t be going back to their homes.”

“It has to be done.” I defend his father to my grave-faced son. “A king cannot tolerate rebels.”

“But he’s selling some of the Cornishmen into slavery,” Arthur tells me flatly.

“Slavery?” I am so shocked that I look at his serious face. “Slavery? Who said so? They must be mistaken?”

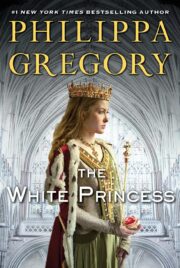

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.