We wait. Henry cannot bring himself to go hawking, but sends me out to dine in the tents in the woods with the hunters and to play the part of a queen who thinks that all is well. I take the children with me on their little ponies, and Arthur on his hunter rides proudly at my side. When one of the lords asks me if the king is not coming I say that he will come in a while, he was detained by some business, nothing of importance.

I doubt very much that anyone believes me. The whole court knows that the boy is somewhere off our coasts; some of them will know that he has landed. Almost certainly, some of them will be preparing to join him, they may even have his letter of array in their pockets.

“I’m not afraid,” Arthur tells me, almost as if he is listening to the words and wondering how they sound. “I am not afraid. Are you?”

I show him an honest face and a genuine smile. “I’m not afraid,” I say. “Not at all.”

When I get back to the palace there is a desperate message from Courtenay. The rebels have broken in through the gates of Exeter, and he is wounded. With the walls breached, he has made a truce. The rebel army has been merciful, there has been no looting, they have not even taken him prisoner. Honorably, they release him and in return he has allowed them to go on, along the Great West Way, heading for London, and he has promised he will not pursue them.

“He let them go?” I ask disbelievingly. “To march on London? He promised not to pursue them?”

“No, he’ll break his word,” Henry says. “I will order him to break his word. A promise to rebels like that need not be kept. I’ll order him to trail behind them, block their retreat. Lord Daubney will come down on them from the north, Lord Willoughby de Broke will attack from the west. We will crush them.”

“But he made a promise,” I say uncertainly. “He has given his word.”

Henry’s face is dark and angry. “No promise given to that boy counts before God.”

His servants come in with his hat, his gloves, his riding boots, his cape. Another goes running to the stables to order his horses, the guard is mustering in the yard, a messenger is riding for all the guns and cannon that London has.

“You’re going to your army?” I ask. “You’re riding out?”

“I’ll meet with Daubney and his army,” he says. “We’ll outnumber them by three to one. I’ll fight him with odds like these.”

I catch my breath. “You’re going now?”

He kisses me perfunctorily, his lips cold, and I can almost smell the scent of his fear. “I think we’ll win,” he says. “As far as I can be certain, I think we’ll win.”

“And what will you do then?” I ask. I dare not name the boy and ask what Henry plans for him.

“I will execute everyone who has raised a hand against me,” he says grimly. “I will show no mercy. I will fine everyone who let them march by and did not stop them. When I have finished, there will be no one left in Cornwall and Devon but dead men and debtors.”

“And the boy?” I ask quietly.

“I will bring him into London in chains,” he says. “Everyone has to see that he is a nobody, I will throw him down into the dust and when everyone understands at last that he is a boy and no prince, I will have him killed.”

He looks at my white face. “You will have to see him,” he says bitterly, as if all of this is my fault. “I will want you to look him in the face and deny him. And you had better make sure that you say no word, give no look, not a whisper, not even a breath of recognition. Whoever he looks like, whatever he says, whatever nonsense he spouts when he is asked: you had better be sure that you look at him with the gaze of a stranger, and if anyone asks you, you don’t know him.”

I think of my little brother, the child that my mother loved. I think of him looking at picture books on my lap, or running around the inner courtyard at Sheen with a little wooden sword. I think that it will not be possible for me to see his merry smile and his warm hazel eyes and not reach out to him.

“You will deny him,” Henry says flatly. “Or I will deny you. If you ever, by so much as a word, the whisper of a word, the first letter of a word, give anyone, anyone to understand that you recognize this imposter, this commoner, this false boy, then I will put you aside and you will live and die in Bermondsey Abbey as your mother did. In disgrace. And you will never see any of your children again. I will tell them—each one of them—that their mother is a whore and a witch. Just like her mother, and her mother before that.”

I face him, I rub his kiss from my mouth with the back of my hand. “You need not threaten me,” I say icily. “You can spare me your insults. I know my duty to my position and to my son. I’m not going to disinherit my own son. I will do as I think right. I am not afraid of you, I have never been afraid of you. I will serve the Tudors for the sake of my son—not for you, not for your threats. I will serve the Tudors for Arthur—a true-born king of England.”

He nods, relieved to see his safety in my unquestionable love for my boy. “If any one of you Yorks speaks of the boy other than as a young fool and a stranger, I will have him beheaded that same day. You will see him on Tower Green with his head on the block. The moment that you or your sisters or your cousin or any of your endless cousins or bastard kinsmen recognize the boy is the moment that you sign the warrant for his execution. If anyone recognizes him then they die and he dies. D’you understand?”

I nod my head and I turn away from him. I turn my back on him as if he were not a king. “Of course I understand,” I say contemptuously over my shoulder. “But if you are going to continue to claim that he is the son of a drunken boatman from Tournai, you must remember not to have him beheaded like a prince on Tower Green. You’ll have to have him hanged.”

I shock him, he chokes on a laugh. “You’re right,” he says. “His name is to be Pierre Osbeque, and he was born to die on the gallows.”

With ironic respect I turn back to him and sweep a curtsey, and in this moment I know that I hate my husband. “Clearly, we will call him whatever you wish. You can name the young man’s corpse whatever you wish, that will be your right as his murderer.”

We do not reconcile before he rides out and so my husband goes out to war with no warm farewell embrace from me. His mother gives him her blessing, clings to his reins, watches him go while she whispers her prayers, and looks curiously at me, as I stand dry-eyed and watch him ride off at the head of his guard, three hundred of them, to meet with Lord Daubney.

“Are you not afraid for him?” she asks, her eyes moist, her old lips trembling. “Your own husband, going out to war, to battle? You did not kiss him, you did not bless him. Are you not afraid for him riding into danger?”

“Really, I doubt very much that he’ll get too close,” I say cruelly, and I turn and go inside to the second-best apartment.

EAST ANGLIA, AUTUMN 1497

But England is not as it was. The king’s writ runs up to the high altar now, his mother and her friend the archbishop have made sure of that. There is no sanctuary for the boy though he claims it as a king ordained by God to rule. The abbey breaks its own time-honored traditions, and hands over the boy. Unwillingly, he has to come out to make his surrender to a king who rules England and the Church too.

He came out wearing cloth of gold, and answering to the name of Richard IV—a hastily scribbled note which I guess is from my half brother, Thomas Grey, is tucked under my stirrup when I am taking the children out on their ponies. I did not see the hand that tied it to the stirrup leathers and I can be sure that no one will ever say that I saw it and read it. But when the king questioned him, he denied himself. So be it. Mark it well. If he himself denies it, we can deny him.

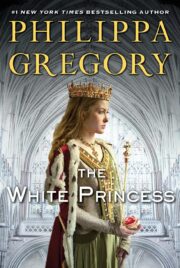

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.