Henry gives me his arm to lead me in to dinner and the rest of the court take their places behind us, my ladies following me in order of precedence, the gentlemen behind them. Lady Katherine Huntly, her dark eyes fixed modestly on the ground, takes her rightful place behind My Lady the King’s Mother. As Henry and I lead the way down the wide stone stairs to the great hall to the blast of trumpets and the murmur of applause from the people who have crowded into the gallery to see the royal family at their dinner, I sense, more than I actually see, that the boy who is to be called Peter Warboys, or perhaps Pero Osbeque or John Perkin, has walked past the woman who was once his wife, bowed his head low to her, and taken his place with the other young noblemen of Henry’s court.

The boy seems to be at home at court. He goes from hall to stable to hawking mews to gardens and he is never seen to miss his way, never asks anyone which is the direction of the treasure house, or where would he find the king’s tennis court? He will fetch a pair of gloves for the king without asking where they are kept. He is comfortable with his companions, too. There is an elite of handsome young men who lounge in the king’s rooms and run errands for him, who like to call at my rooms to listen to the music and chatter with my ladies. When there are cards they are quick to take a hand, if there is archery they will take a bow and excel each other. Gambling, they are free with money; dancing, they are graceful on the floor; flirting is their principal occupation, and every one of my ladies has a favorite among the king’s young men and hopes that he sees her half-hidden glance.

The boy falls into this life as if he had been born and bred at a graceful court. He will sing with my lutenist if invited, he will read in French or Latin if someone hands him the storybook. He can ride any horse in the stables with the relaxed, easy confidence of a man who has been in the saddle since he was a boy, he can dance, he can turn a joke, he can compose a poem. When they put on an impromptu play he is quick and witty, when called to recite he has lengthy poems by heart. He has all the skills of a well-educated young nobleman. He is, in every way, like the prince he pretended to be.

Indeed, he stands out from these handsome young men in only one thing. Night and morning he greets Lady Katherine by kneeling at her feet and kissing her outstretched hand. Every morning, first thing, on the way to chapel, he drops down to his knee, pulls his hat from his head, and kisses, very gently, the hand she holds out to him and stays still for the brief moment that she rests her hand on his shoulder. In the evening, when we leave the great hall, or when I say that the music must stop in my rooms, he bows low to me with his odd, familiar smile, and then he turns to her and kneels at her feet.

“He must be ashamed that he brought her so low,” Cecily says after we have all observed this for several days. “He must be kneeling for her forgiveness.”

“Do you think so?” Maggie asks her. “Don’t you think that it is the only way that he can touch her? And she touch him?”

I watch them more closely after that, and I believe Maggie is right. If he can pass something to her, he makes sure that their fingertips brush. If the court is riding he is quickly at the shoulder of her horse to lift her into the saddle, and at the end of the day he is first into the stable yard, his own horse’s reins tossed to a groom so that he can lift her down, holding her for one moment before putting her gently on her feet. When they are playing cards their shoulders lean together at the table, when he is standing beside her horse and she is mounted high above him, he steps backwards until his fair head can brush against her saddle and her hand can drop from the reins to touch the nape of his neck.

She never rebuffs him, she does not avoid his touch. Of course, she cannot; while she is his wife she must be obedient to him. But clearly, there is a passion between them that they do not even try to hide. When they pour the wine at dinner he looks from his table over to hers and raises his glass to her and gets a quick half-hidden smile in return. When she walks past the young men playing at cards she pauses, just for a moment, to look at his hand, and sometimes leans down as if to see better, and he leans back and their cheeks brush, like a kiss. Throughout the court they move, two exceptionally beautiful young people, kept apart by the specific order of the king and yet going through the day in parallel; always with one eye on the other, like performers separated by the movement of a dance who are certain to come together again.

Now that it is safe to travel in England again, Arthur my son must go to Ludlow Castle and Maggie and his guardian Sir Richard Pole will attend him. I see them off from the stable yard, my half brother Thomas Grey at my side.

“I can’t bear to let him go,” I say.

He laughs. “Don’t you remember our mother when Edward had to go? Lord save her, she went with him, all that long way, even though she was pregnant with Richard. It is hard for you, and hard on the boy. But it is a sign that things are getting back to normal. You should be glad.”

Arthur, bright and excited high on his horse, waves his hand at me and follows Sir Richard and Maggie out of the stable yard. The guard falls in behind him.

“I don’t think I can be glad,” I say.

Thomas squeezes my hand. “He’ll be back for Christmas.”

Next day the king tells me he will take a small company to London to show the crowds Perkin Warbeck, the pretender.

“Who’s going with you?” I ask, as if I don’t understand.

Henry flushes slightly. “Perkin,” he says. “Warbeck.”

Finally they have settled on a name for him, and not just for him. They have named and described a whole family Warbeck with uncles and cousins and aunts and grandparents, the Warbecks of Tournai. But though this extensive family is established, at least on paper, all with occupations and addresses, none of them is summoned to see him. None of them writes to him with reproaches, or offers of help. Though there are so many of them, so well recorded, not one offers a ransom for his return. The king weaves them into the story of Perkin Warbeck and we never ask to see them, any more than one might ask to see a black cat or a crystal slipper or a magic spindle.

In London the boy gets a confused reception. The men, who have seen their taxes rise and rise and unlawful fines invade every part of their income, curse him for the expense that his invasions have caused, and groan at him as he rides by. The women, always quick to malice, start by catcalling and throwing dirt; but even they soften, they cannot help but admire his downturned face, his shy smile. He rides through the streets of London with the modest air of a boy who could not help himself, who was called and answered a call, who could not help but be himself. Some people rage against him, but many shout out that he is a fair boy, a rose.

Henry makes him go on foot, leading a broken-down old horse, with one of his followers in chains, mounted up. The man in the saddle, grim-faced, is the sergeant farrier who ran from Henry’s service to be with the boy. Now all of London can see him, head bowed, bruised, tied to the saddle like a Fool. Usually people would throw filth, and then laugh to see the rider and the humiliated groom spattered with mud from the gutters, showered with the contents of chamber pots flung from overhead windows. But the boy and his defeated supporter make a strangely silent pair as they go through the narrow streets to the Tower and then someone says, terribly clearly, into a sudden hush: “Look at him! He’s the spit of good King Edward.”

Henry hears of this the moment the words are out of the man’s mouth; but too late to call the words back, too late to deafen the crowd. All he can do is make sure that the crowd never again sees the boy who looks so like a York prince.

So that is to be the first and last time that the boy has to walk the streets of London inviting abuse. “You will confine him to the Tower,” My Lady orders her son.

“In time. I wanted the people to see that he was nothing, no threat, an idle foolish boy. Nothing more than a little lad, the boy that I always called him—lighter than air.”

“Well, they have seen him now. And they don’t call him lighter than air. They don’t know what to call him, though we have told them his name over and over again. And the name that they want to give him should never be spoken. Surely, now you will charge him and execute him?”

“I gave him my word that he should not be killed when he surrendered to me.”

“That’s not binding.” Anxiety makes her overrule him. “You’ve broken your word for less than this. You don’t have to keep your word to such as him.”

His face is suddenly illuminated. “Yes, but I gave my word to her.”

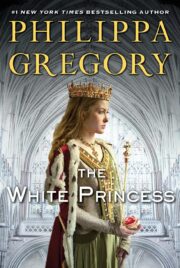

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.