Even the boy is given two servants of his own who go with him everywhere and serve him, fetching his horse, attending him when he rides, preparing his bedchamber, squiring him in to dine. They sleep in his room, one on a pallet bed, one on the floor, so that they are, as it were, his jailers; but when the boy turns to one of them to give him his gloves or ask for his cape, it is clear that they serve him gladly. He lives in the king’s side of the building, in the rooms inside the royal wardrobe, guarded like treasure. The doors to the wardrobe and the treasure house are locked at night so that—without being imprisoned in any way—it happens that he is locked inside each night, as if he were a precious jewel himself. But during the day he walks in and out of the palace, nodding casually to the yeomen of the guard as he strolls by, rides out on a fast horse, either with the court or on his own or with his chosen friends, who seem proud to ride with him. He takes a boat out on the river, where he is not watched nor prevented from rowing as far as he likes. He is as free and as lighthearted as any of the young men of this young, lighthearted court, but he seems—without ever claiming preeminence—to be a natural leader, finer than his peers, acknowledged by them almost as if he were a prince.

In the evening he is always in my rooms. He comes in and bows to me, says a few words of greeting, smiles that curiously warm and intimate smile, and then seats himself near to Katherine Huntly. Often we see them talking, head to head, low-voiced, but there is no sense of conspiracy. When anyone comes near them they look up and make a place for whoever passes by, they are always courteous and charming and easy. If they are left alone they speak and reply, question and answer, almost as if they were singing together, almost as if they wanted nothing more than to hear each other’s voice. They may talk of the weather, of the score in the archery competition, of almost nothing; but everyone senses their irresistible affinity.

Often I see them sitting in the oriel window, side by side, shoulder brushing against shoulder, knees just touching. Sometimes he leans forwards and whispers in her ear and his lips nearly brush her cheek. Sometimes she turns her face towards him and he must feel her warm breath on his neck, as close as a kiss. For hours in the day they will sit like this, quiet as obedient children on a settle, tender as young lovers before their betrothal, never touching, but never more than a hand-span apart, like a pair of cooing doves.

“My God, he adores her,” Maggie remarks, watching this restrained, unstoppable courtship. “Surely he cannot always be at arm’s length? Do they never slip away to her rooms?”

“I don’t think so,” I say. “They seem to have settled for being constant companions, but no longer husband and wife.”

“And the king?” Maggie asks delicately.

“Why, what have you heard?” I ask dryly. “You’ve only been at court a few days, people must have rushed to tell you everything. What have you heard already?”

She makes a grimace. “It’s common talk that he can’t take his eyes off her, when they ride out he is always near her, when he dances he asks for her as his partner, he sends out the best dishes for her. He is constantly offering gifts which she quietly returns, again and again he sends her to the royal wardrobe, he orders silks for new gowns, but she will only wear black.” She looks at me, and finds me impassive. “You’ve seen all this? You know all this?”

I shrug. “I have seen most of it now, with my husband. I saw it once before with someone else’s husband. I was once the girl that everyone watched as they turned their backs on the queen. I was once the girl that got the gowns and the gifts.”

“When you were the king’s favorite?”

“Just as she is. Worse than she is, for I gloried in it. I was in love with Richard and he was in love with me and we courted right under the nose of his wife, Anne. I wouldn’t do that now. I would never do that now. I didn’t realize then how painful it is.”

“Painful?”

“And demeaning. For the wife. I see the court look at me as they wonder what I am thinking. I see Henry look at me as if he hopes that I don’t notice that he stammers like a boy when he talks to her. And she . . .”

Maggie waits.

“She never looks at me at all,” I say. “She never looks at me to see how I am taking it, or to see if I notice her triumph. She never looks at me to see if I observe that my husband adores her; and oddly it is only her gaze that I could endure. When she curtseys to me or speaks to me, I think she is the only person who understands how I feel. It is as if she and I are in this together, and we have to manage it somehow together. She cannot help that he has fallen in love with her. She does not seek his favor, she does not entice him. Neither she nor I can help it that he has fallen out of love with me, and in love with her.”

“She could leave!”

“She can’t leave,” I say. “She can’t leave her husband, she could not bear to leave him here, and Henry seems determined that he shall live at court, live here like a kinsman almost as if he were . . .”

“As if he were your brother?” Maggie whispers, quiet as a breath.

I nod. “And Henry won’t let her go. He looks for her every morning in chapel, he can’t close his eyes and say his prayers until he has seen her. It makes me feel . . .” I break off and I blot my eyes with the corner of my sleeve. “I’m such a fool but it makes me feel unwanted. It makes me feel plain. I don’t feel like the first lady of the court of England. I don’t feel that I am where I should be, in my mother’s place. I’m not even in my usual second place to My Lady the King’s Mother. I have dropped below that. I am humbled. I am Queen of England but disregarded by the king my husband, and the court.” I pause and try to laugh, but it comes out as a sob. “I feel plain, Maggie! For the first time in my life! I feel humbled! And it’s hard.”

“You are the first lady, you are the queen, nobody and nothing can take that from you,” she insists fiercely.

“I know. I know that really,” I say sadly. “And I married without love, and now it seems that he loves someone else. It is ridiculous that I should care at all. I married him thinking of him as my enemy. I married him hating him and hoping for his death. It should be nothing to me that he now lights up when another woman enters the room.”

“But you do care?”

“Yes. I find that I do.”

The court prepares joyfully for Christmas. Arthur is summoned to his father, who tells him that his betrothal to the Spanish princess Katherine of Aragon is confirmed and will take place. Nothing can delay it, now that the monarchs of Spain are confident that there is no pretender threatening Henry’s throne. But they write to their ambassador to ask him why the pretender has not been executed, as they had expected either his death in battle or a prompt beheading on the battlefield. Why has he not been put on trial and swiftly dispatched?

Lamely, the ambassador replies to them that the king is merciful. As merciless usurpers themselves, they do not understand this, but they allow the betrothal to go ahead, stipulating only that the pretender should die before the marriage ceremony. That is mercy enough, they suggest. The ambassador hints to the king that Isabella and Ferdinand, the King and Queen of Spain, would prefer it if there was not a drop of doubtful blood left in the country, not Perkin Warbeck, nor Maggie’s brother; they would prefer it if there were no heir of York at all.

“Not Lady Huntly’s baby?” I ask. “Shall we be Herods now?”

Arthur comes to walk with me in the garden, where I am huddled in my furs and striding out for warmth, my ladies trailing away behind me. “You look cold.”

“I am cold.”

“Why don’t you go indoors, Lady Mother?”

“I am sick of being indoors. I am sick of everyone watching me.”

He offers me his arm, which I take with such a glow of pleasure to see my boy, my firstborn child, with the manners of a prince.

“Why are they watching you?” he asks gently.

“They want to know how I feel about Lady Katherine Huntly,” I say frankly. “They want to know if she troubles me.”

“Does she?”

“No.”

“His Grace, my father, seems very happy to have captured Mr. Warbeck,” he begins carefully.

I cannot help but giggle at my boy Arthur practicing diplomacy. “He is,” I say.

“Though I am surprised to find Mr. Warbeck in favor, and at court. I thought that my father was taking him to London and would imprison him in the Tower.”

“I think we are all surprised at your father’s sudden mercy.”

“It’s not like Lambert Simnel,” he says. “Mr. Warbeck isn’t a falconer. What is he doing coming and going so freely? And is my father paying him a wage? He seems to have money to pay for books and to gamble. Certainly my father gives him the best clothes and horses, and his wife, Lady Huntly, lives in state.”

“I don’t know,” I say.

“Does he spare him for your sake?” he asks very quietly.

My face is quite expressionless. “I don’t know,” I say again.

“You do know, but you won’t say,” Arthur asserts.

I hug his arm. “My son, some things are safer left unsaid.”

He turns to face me, his innocent face puzzled. “Lady Mother, if Mr. Warbeck is indeed who he said he was, if he is being allowed the run of the court for that reason, then he has a greater right to the throne than my father. He has a greater right to the throne than me.”

“And that is exactly why we will never have this conversation,” I reply steadily.

“If he is who he says he is, then you must be glad he is alive,” he pursues, with all the doggedness of a young man in pursuit of the truth. “You must be glad to see him. It must be as if he were snatched from death, almost as if he were risen from the dead. You must be happy to see him here, even if he never sits on the throne. Even if you pray that he never sits on the throne. Even if you want the throne for me.”

I close my eyes so that he does not see the glow of my happiness. “I am,” I say shortly; and he is a wise young prince, for he does not speak of this again.

We have dancing and celebrating, a joust and players. We have a choir sing most beautifully in the royal chapel, and we give away sweetmeats and gingerbread to two hundred poor children. The broken meats from the feast feed hundreds of men and women at the kitchen door for the twelve days. Henry and I lead out the dancers on the first day of Christmas, and I look behind me, down the line and see that Lady Katherine is dancing with her husband, and they are handclasped, both flushed, the handsomest couple in the room.

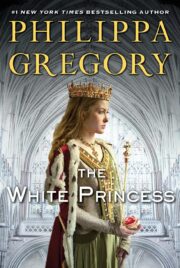

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.