“Yes,” she acknowledges. I see her gray eyes narrow as she watches the gloriously gilded barge and the proud flap of the standards. “But I always find her so very . . . unconvincing, even in her greatest triumphs,” she says.

“Unconvincing?” I repeat the odd word.

“She always looks to me like a woman who has been badly treated,” my mother says, and she laughs joyously out loud, as if defeat is just a turn of the wheel of fortune and Lady Margaret is not on the rise and an instrument of the glorious will of God as she thinks, but has just been lucky on this turn, and is almost certain to fall on the next. “She always looks to me like a woman who has much to complain about,” my mother explains. “And women like that are always badly treated.”

She turns to look at me, and laughs aloud at my puzzled expression. “It doesn’t matter,” she says. “At any rate, we have her word that Henry will marry you, as soon as he is crowned, and then we’ll have a York girl on the throne.”

“He shows few signs of wanting to marry me,” I say dryly. “I am hardly honored in the coronation procession. It’s not us on the royal barge.”

“Oh, he’ll have to,” she says confidently. “Whether he likes it or not. The Parliament will demand it of him. He won the battle, but they won’t accept him as king without you at his side. He has had to promise. They’ve spoken to Thomas, Lord Stanley, and he, of all men, understands the way that power lies. Lord Stanley has spoken to his wife, she has spoken to her son. They all know that Henry has to marry you, like it or not.”

“And what if I don’t like it?” I turn to her and put my hands on her shoulders so she cannot glide away from my anger. “What if I don’t want an unwilling bridegroom, a pretender to the crown, who won his throne through disloyalty and betrayal? What if I tell you that my heart is in an unmarked grave somewhere in Leicester?”

She does not flinch, but confronts my angry grief, her face serene. “Daughter mine, you have known for all your life that you would be married for the good of the country and the advancement of your family. You will do your duty like a princess, wherever your heart is buried, whoever you want or don’t want, and I expect you to look happy as you do it.”

“You’ll marry me to a man that I wish were dead?”

Her smile does not waver. “Elizabeth, you know as well as I do that it is rare that a young woman can marry for love.”

“You did,” I accuse.

“I had the sense to fall in love with the King of England.”

“So did I!” breaks from me like a cry.

She nods and puts her hand gently on the nape of my neck, and when I yield to her, she pulls my head to her shoulder. “I know, I know, my love. Richard was unlucky that day, and he had never been unlucky before. You would have thought he was certain to win. I thought he was certain to win. I too staked my hopes and my happiness on his winning.”

“Do I really have to marry Henry?”

“Yes, you do. You will be Queen of England and return our family to greatness. You will restore peace to England. These are great things to achieve. You should be glad. Or, at the very least, you can look glad.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, NOVEMBER 1485

They restore Henry’s mother to her family fortune and properties; nothing is more important than building the wealth of this most powerful king’s mother. Then they promise to pay my mother’s pension as a dowager queen. They also agree that Richard’s law that ruled my mother and father were never legally married must be dismissed as a slander. More than that, it must be forgotten, and nobody is ever to repeat it. At a stroke of the pen from the Tudor Parliament, we are restored to our family name and I and all my sisters are legitimate princesses of York once more. Cecily’s first marriage is forgotten; it is as if it never was. She is Princess Cecily of York once again and free to be married to Lady Margaret’s kinsman. In Westminster Palace, the servants now bend their knee to present a dish, and everyone calls each of us “Your Grace.”

Cecily delights in our sudden restoration to our titles, all of us York princesses are glad to be ourselves once again; but I find my mother walking in silence by the cold river, her hood over her head, her cold hands clasped in her muff, her gray eyes on the gray water. “Lady Mother, what is it?” I go to take her hands and look into her pale face.

“He thinks my boys are dead,” she whispers.

I look down and see the mud on her boots and on the hem of her gown. She has been walking beside the river for an hour at least, whispering to the rippling water.

“Come inside, you’re freezing,” I say.

She lets me take her hand and lead her up the graveled path to the garden door, and help her up the stone stairs to her privy chamber.

“Henry must have certain proof that both my boys are dead.”

I take off her cloak and press her into a chair beside the fire. My sisters are out, walking to the houses of the silk merchants, gold in their purses, servants to carry their purchases home, served on bended knee, laughing at their restoration. Only my mother and I struggle here, locked in grief. I kneel before her and feel the dry rushes under my knees release their cold perfume. I take her icy hands in mine. Our heads are so close together that no one, not even someone listening at the door, could hear our whispered conversation.

“Lady Mother,” I say quietly. “How do you know?”

She bows her head as if she has been struck hard in the heart. “He must do. He must be absolutely sure that they are both dead.”

“Were you still hoping for your son Edward, even now?”

A little gesture, like that of a wounded animal, tells me that she has never stopped hoping that her eldest York son had somehow escaped from the Tower and still lived, somewhere, against the odds.

“Really?”

“I thought I would know,” she says very quietly. “In my heart. I thought that if my boy Edward had been killed I would have known in that moment. I thought that his spirit could not have left this world and not touched me as he went. You know, Elizabeth, I love him so much.”

“But, Mother, we both heard the singing that night, the singing that comes when one of our house is dying.”

She nods. “We did. But still I kept on hoping.”

There is a little silence between us, as we observe the death of her hope.

“D’you think Henry has made a search and found the bodies?”

She shakes her head. She’s certain of this. “No. For if he had the bodies, he would show them to the world and give them a great funeral for everyone to know they’re gone. If he had the bodies, he would give them a royal burial. He’d have us all draped in darkest blue, in mourning for months. If he had any firm evidence, he would use it to blacken Richard’s name. If he had anyone he could accuse of murder, he would put him on trial and publicly hang him. The best thing in the world for Henry would have been to find two bodies. He will have been praying ever since he landed in England that he would find them dead and buried, so that his claim to the throne was secure, so that nobody could ever rise up and impersonate them. The only person in England who wants to know more urgently than me where my sons are tonight is Henry the new king.

“So he can’t have found their bodies, but he must be certain that they are dead. Someone must have promised him that they were killed. Someone that he must trust. Because he would never have restored the royal title to our family if he thought we had a surviving boy. He would never have made you girls princesses of York if he thought that somewhere there was also a living prince.”

“So he’s been assured that both Edward and Richard are dead?”

“He must be sure. Otherwise, he would never have ruled that your father and I were married. The act that makes you a princess of York again makes your brothers princess of York. If our Edward is dead, then your younger brother is King Richard IV of England, and Henry is a usurper. Henry would never have restored a royal title to a live rival. He must be sure that both the boys are dead. Someone must have sworn to him that the murder was truly done. Someone must have told him, without doubt, that they killed two boys and saw them dead.”

“Could it be his mother?” I whisper.

“She’s the only one with reason to kill them, who was here when they disappeared, who is alive now,” my mother says. “Henry was in exile, his uncle Jasper with him. Henry’s ally the Duke of Buckingham might have done it; but he’s dead, so we’ll never know. If someone has reassured Henry, just now, that he is safe, then it must be his mother. The two of them must have convinced themselves that they are safe. They think both York princes are dead. Next, he will propose marriage to you.”

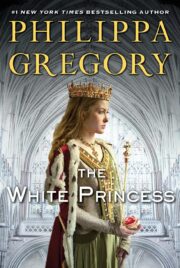

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.