Thomas faces her. “He went up to the scaffold with courage,” he said. “His hands were tied behind his back and they helped him gently up the ladder. There were hundreds there, thousands, pushing to see, they had built the scaffold very high so that everyone could see him. But there was no one catcalling or shouting. It was as if they were sorry. Or curious. Some people were crying. It wasn’t like a traitor’s execution at all.”

She nods rapidly, swallowing tears.

“He spoke very briefly, saying he was not who he had pretended to be, then he went up the ladder and they put the noose around his neck. He looked around for a moment, just for a moment, as if he thought something might happen . . .”

“Was he hoping for a pardon?” she breathes, her face agonized. “I could not get him a pardon. Did he think he might be pardoned?”

“Perhaps a miracle,” Thomas suggests. “He looked around and then he bent his head and prayed and they took the ladder out from under his feet and he dropped.”

“Was it quick?” Margaret whispers.

“It took an hour, or perhaps more,” Thomas said. “No one was allowed close to him, so nobody could drag hold of his feet and break his neck to make it quicker. But he hung quietly enough, and then he was gone. He died like a brave man, and the people at the front of the scaffold were praying for him, all the time.”

Lady Katherine drops to her knees and bows her head in prayer, Margaret closes her eyes. Thomas looks from one to another of us, three grieving women.

“So it’s over,” I say. “This whole long joust of fear and playacting and deception and deceit is over.”

“Except for Teddy,” Margaret says.

Margaret and I go together to the king to try to save Teddy but he will not see us. Margaret’s husband, Sir Richard, comes to me in my rooms and begs me not to intercede for his wife’s only brother. “Better for us all if he is put to the death than returned to that prison,” he says bluntly. “Better for us all if the king does not think of Margaret as a woman of the House of York. Better for us all if the young man dies now, without a rebellion forming around him again. Please, Your Grace, teach Margaret to see this with patience. Please, teach her to let her brother go. It’s been no life for him, not since he was a little boy. Let it end here, and then perhaps people will forget that my son is of the House of York and he, at least, will be safe.”

I hesitate.

“The king is hunting Edmund de la Pole,” he says. “The king wants all of the House of York sworn to his service or dead. Please, Your Grace, tell Margaret to give up her brother that she may keep her son.”

“Like me?” I whisper, too low for him to hear.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, 28 NOVEMBER 1499

There is a clap of lightning that makes him stop in his tracks like a nervous colt. He has never been out in a storm. For thirteen years, he has not felt rain on his face.

My half brother Thomas Grey tells me that he thinks that Teddy did not know what was going to happen to him. He confesses his little sins and gives a penny to the headsman when they tell him to do so. He was always obedient, always trying to please. He puts his fair York head down on the block and he stretches out his arms in the gesture of assent. But I don’t think he ever knew that he was agreeing to the scything down of the axe and the end of his little life.

Henry will not dine in the great hall of Westminster that night, his mother is at prayer. In their absence, I have to walk in alone, at the head of my ladies, Katherine behind me in deepest black, Margaret wearing a gown of dark blue. The hall is hushed, the people of our own household quiet and surly, as if some joy has been taken from us, and we will never get it back.

There is something different about the hall as I walk through the silent court and when I am seated, and can look around, I see what has changed. It is how they have seated themselves. Every night the men and women of our extensive household come in to dine and sit in order of precedence and importance, men on one side, women on the other of the great hall. Each table seats about twelve diners and they share the common dishes that are placed in the center of the table. But tonight it is different; some tables are overcrowded, some have empty places. I see that they have grouped themselves regardless of tradition or precedent.

Those who befriended the boy, those who were of the House of York, those who served my mother and father or whose fathers served my mother and father, those who love me, those who love my cousin Margaret and remember her brother Teddy—they have chosen to sit together; and there are many, many tables in the great hall where they are seated in utter silence, as if they have sworn a vow never to speak again, and they look around them saying nothing.

The other tables are those that have taken Henry’s side. Many of them are old Lancastrian families, some of them were in his mother’s household or serve her wider family, some came over with him to fight at Bosworth, some, like my half brother Thomas Grey or my brother-in-law Thomas Howard, spend every day of their lives trying to show their loyalty to the new Tudor house. They are trying to appear as usual, leaning across the half-empty tables, talking unnaturally loudly, finding things to say.

Almost without trying to, the court has sorted itself into those who are in mourning tonight, wearing gray or black or navy ribbons pinned to their jerkins or carrying dark gloves, and those who are trying, loudly and cheerfully, to behave as if nothing has happened.

Henry would be horrified if he saw the numbers that are openly mourning for the House of York. But Henry will not see it. Only I know that he is facedown on his bed, his cape hunched over his shoulders, unable to walk to dinner, unable to eat, barely able to breathe in a spasm of guilt and horror at what he has done, which can never be undone.

Outside the storm is still rumbling, the skies are billowing with dark clouds and there is no moon at all. The court is uneasy too; there is no sense of victory, and no sense of closing a chapter. The death of the two young men was supposed to bring a sense of peace. Instead we are all haunted by the sense that we have done something very wrong.

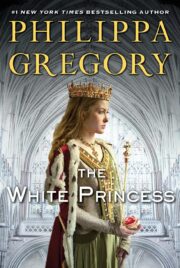

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.