I look across at the table where Henry’s young companions always sit, expecting them at least to be cracking a jest or playing some foolish prank on each other, but they are waiting for dinner to be served in silence, their heads bowed, and when it comes they eat in silence, as if there is nothing to laugh about at the Tudor court anymore.

Then I see something that makes me glance across to the groom of the servery, wondering that he should allow it—certain that he will report it. At the head of the table of the young men, where the boy used to sit, they have put his cup, his knife, his spoon. They have set a plate for him, they have poured wine as if he were coming to dine. In their own way, defiantly, the young men are showing their loyalty to a ghost, a dream; expressing their love for a prince who—if he was ever there at all—is gone now.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, WINTER 1499

But still the king gets no better, and his mother spends all her time in the chapel praying for him, or in his room begging him to sit up, turn his face from the wall, drink a little wine, taste a little meat, eat. The Master of the Revels comes to me to make plans for the Christmas feasts, the dancers must rehearse and the choristers practice new music, but I don’t know if we are going to have a silent court in mourning with an empty throne, and I tell him we can plan nothing until the king is well again.

The other men charged with treason in the last plot for the York prince are all hanged or fined or banished. Occasional pardons are issued in the king’s name, with his initial weakly scrawled at the foot of the page. Nobody knows if he has locked himself up, sick with remorse, or if he is just too tired to go on fighting. The plot is over, but still the king does not come out of his chamber; he reads nothing and will see no one. The court and the kingdom wait for him to return.

I go to visit My Lady the King’s Mother and find her with all the business of the throne on the table before her, as if she were regent. “I have come to ask you if the king is very ill,” I say. “There is much gossip, and I am concerned. He will not see me.”

She looks at me and I see that the papers are shuffled into piles, but she is not reading them, she is signing nothing. She is at a loss. “It’s grief,” she says simply. “It is grief. He is sick with grief.”

I rest my hand on my heart and feel it thud with anger. “Why? Why should he grieve? What has he lost?” I ask, thinking of Margaret and her brother, Lady Katherine and her husband, of my sisters and myself, who go through our days and show the world nothing but indifference.

She shakes her head as if she cannot understand it herself. “He says he has lost his innocence.”

“Henry, innocent?” I exclaim. “He entered his throne through the death of a king! He came into the kingdom as a pretender to the throne!”

“Don’t you dare say it!” She rounds on me. “Don’t you say such a thing! You of all people!”

“But I don’t understand what you mean,” I explain. “I don’t understand what he is saying. He has lost his innocence? When was he innocent?”

“He was a young man, he spent his life aspiring to the throne,” she says, as if the words are forced from her, as if it is a hard confession, choked out of her. “I raised him to be like this, I taught him myself that he must be King of England, that there was nothing else for him but the crown. It was my doing. I said that he should think of nothing but returning to England and claiming his own and holding it.”

I wait.

“I told him it was God’s will.”

I nod.

“And now he has won it,” she says. “He is where he was born to be. But to hold it, to be sure of it, he has had to kill a young man, a young man just like him, a boy who aspired to the throne, who was also raised to believe it was his by right. He feels as if he has killed himself. He has killed the boy that he was.”

“The boy that he was,” I repeat slowly. She is showing me a boy I had not seen before. The boy who was named for the Tournai boatman was also the boy who said he was a prince, but to Henry he was a fellow-pretender, someone raised and trained for only one destiny.

“That was why he liked the boy so much. He wanted to spare him, he was glad to bind himself to forgive him. He hoped to make him look like a nothing, keeping him at court like a Fool, paying for his clothes from the same purse as he paid for his Fool and his other entertainments. That was part of his plan. But then he found that he liked him so much. Then he found that they were both boys, raised abroad, always thinking of England, always taught of England, always told that the time would come when they must sail for home and enter into their kingdom. He once said to me that nobody could understand the boy but him—and that nobody could understand him but the boy.”

“Then why kill him?” I burst out. “Why would he put him to death? If the boy was him, a looking-glass king?”

She looks as if she is in pain. “For safety,” she said. “While the boy lived they would always be compared, there would always be a looking-glass king, and everyone would always look from one to the other.”

She says nothing for a moment and I think of how Henry always knew that he did not seem like a king, not a king like my father, and how the boy that Henry called Perkin always looked like a prince.

“And besides, he could not be safe until the boy was dead,” she says. “Even though he tried to keep him close. Even when the boy was in the Tower, enmeshed in lies, entrapped with his own words, there were people all over the country pledging themselves to save him. We hold England now; but Henry feels that we will never keep it. The boy is not like Henry. He had that gift—the gift of being beloved.”

“And now you will never be safe.” I repeat her words to her and I know that my revenge on them is here, in what I am saying to the woman who has taken my place in the queen’s rooms, behind this table, just as her son took the place of my brother. “You don’t have England,” I tell her. “You don’t have England, and you will never be safe, and you will never be beloved.”

She bows her head as if it is a life sentence, as if she deserves it.

“I shall see him,” I say, going to the door that adjoins his set of rooms, the queen’s doorway.

“You can’t go in.” She steps forwards. “He’s too ill to see you.”

I walk towards her as if I would stride right through her. “I am his wife,” I say levelly. “I am Queen of England. I will see my husband. And you shall not stop me.”

For a moment I think I will have to physically push her aside, but at the last moment she sees the determination in my face and she falls back and lets me open the door and go in.

He is not in the antechamber, but the door to his bedroom is open and I tap on it lightly, and step into his room. He is at the window, the shutters open so that he can see the night sky, looking out, though there is nothing but darkness outside and the glimmering of a scatter of stars like spilled sequins across the sky. He glances round as he sees me come in, but he does not speak. Almost I can feel the ache in his heart, his loneliness, his terrible despair.

“You’ve got to come back to court,” I say flatly. “People will talk. You cannot stay hiding in here.”

“You call it hiding?” he challenges.

“I do,” I say without hesitation.

“They are missing me so much?” he asks scathingly. “They love me so much? They long to see me?”

“They expect to see you,” I say. “You are the King of England, you have to be seen on your throne. I cannot carry the burden of the Tudor crown alone.”

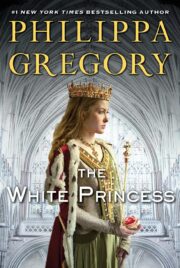

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.