“I didn’t think it would be so hard,” he says, almost an aside.

“No,” I agree. “I didn’t think it would be so hard either.”

He rests his head against the stone window arch. “I thought once the battle was won, it would be easy. I thought I would have found my heart’s desire. But—d’you know?—it is worse being a king than being a pretender.”

He turns and looks at me for the first time in weeks. “Do you think I have done wrong?” he asks. “Was it a sin to kill the two of them?”

“Yes,” I say simply. “And I am afraid that we will have to pay the price.”

“You think we will see our son die, that our grandson will die and our line end with a Virgin Queen?” he asks bitterly. “Well, I have had a prophecy drawn up, and by a more skilled astrologist than you and your witch mother. They say that we will live long and in triumph. They all tell me that.”

“Of course they do,” I say honestly. “And I don’t pretend to foresee the future. But I do know that there is always a price to be paid.”

“I don’t think our line will die out,” he says, trying to smile. “We have three sons. Three healthy princes: Arthur, Henry, and Edmund. I hear nothing but good of Arthur, Henry is bright and handsome and strong, and Edmund is well and thriving, thank God.”

“My mother had three princes,” I reply. “And she died without an heir.”

He crosses himself. “Dear God, Elizabeth, don’t say such a thing. How can you say such things?”

“Someone killed my brothers,” I say. “They both died without saying good-bye to their mother.”

“They didn’t die at my hand!” he shouts. “I was in exile, miles away. I didn’t order their deaths! You can’t blame me!”

“You benefit from their deaths.” I pursue the argument. “You are their heir. And anyway, you killed Teddy, my cousin. Not even your mother can deny that. An innocent boy. And you killed the boy, the charming boy, for being nothing but beloved.”

He puts one hand over his face and blindly stretches his other hand out to me. “I did, I did, God forgive me. But I didn’t know what else to do. I swear there was nothing else I could do.”

His hand finds mine and he grips it tightly, as if I might haul him out from sorrow. “Do you forgive me? Even if no one else ever does. Can you forgive me? Elizabeth? Elizabeth of York—can you forgive me?”

I let him draw me to his side. He turns his head towards me and I feel that his cheeks are wet with tears. He wraps his arms around me and he holds me tightly. “I had to do it,” he says into my hair. “You know that we would never have been safe while he was alive. You know that people would have flocked to him even though he was in prison. They loved him as if he was a prince. He had all that charm, all that irresistible York charm. I had to kill him. I had to.”

He is holding me as if I can save him from drowning. I can hardly speak for the pain I feel but I say: “I forgive you. I forgive you, Henry.”

He gives a hoarse sob and he puts his anguished face against my neck. I feel him tremble as he clings to me. Over his bent head I look at the stained-glass windows of his room, dark against the dark sky, and the Tudor rose, white with a red core, that his mother has inset into every window of his room. Tonight it does not look to me as if the white rose and the red are blooming together as one, tonight it looks as if the white rose of York has been stabbed in its pure white heart and is bleeding scarlet red.

Tonight, I know that I do indeed have much to forgive.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The support that the dowager queen Elizabeth gave to the Simnel rebellion suggests to me that she was fighting Henry VII (and her own daughter) for a preferred candidate. I cannot think she would have risked her daughter’s place on the throne for anyone but her son. She died before the young man who claimed to be Richard landed in England, but it seems that her mother-in-law, Duchess Cecily, supported the pretender. Sir William Stanley’s support (for the pretender against his brother’s stepson) is also recorded. Stanley went to his death without apologizing for taking the side of the pretender; this suggests to me that he thought that the pretender might win, and that his claim was good.

The treatment of the young man who was eventually so uncertainly named as Perkin Warbeck is also very odd. I suggest that Henry VII plotted to get “the boy” out of his court by setting a fire in the royal wardrobe which blazed out of control and destroyed the Palace of Sheen, subsequently engineered his escape, and then finally entrapped him in a treasonous conspiracy with the Earl of Warwick.

Most historians would agree that the conspiracy with Warwick was allowed if not sponsored by Henry VII to remove the two threats to his throne, and their deaths were indeed requested by the Spanish king and queen before they would allow the marriage of the infanta and Prince Arthur.

It is possible that we will never know the identity of the young man who claimed to be Prince Richard and confessed to being “Perkin Warbeck.” What we can be sure of is that the Tudor version of events is not the truth. Anne Wroe’s meticulous research shows the construction of the lie.

This book does not claim to reveal the truth either: it is a fiction based on many studies of these fascinating times and gives, I hope, an insight into the untold stories and the unknown characters with affection and respect.

Touchstone Reading Group Guide

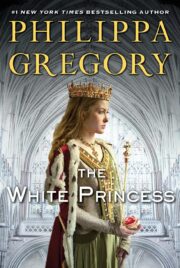

The White Princess

By Philippa Gregory

The White Princess opens with Elizabeth of York grieving the loss of her lover, Richard III, who was killed at the battle of Bosworth by his Lancastrian rival, Henry Tudor. As soon as Henry claims the crown to become Henry VII, he cements his succession by demanding Elizabeth’s hand in marriage.

While Elizabeth dutifully bears a male Tudor heir and endures her husband’s suspicion of her York relations, her mother, Elizabeth of Woodville, concocts a plan for revenge. Making the most of her York connections, Elizabeth Woodville secretly supports an uprising against Henry, placing her daughter, now Queen to Henry’s King, between two families.

When Henry learns of the treasonous plot, he imprisons his mother-in-law and becomes preoccupied with capturing “the boy”—the handsome leader of the rebellion whose adherents claim is the true York heir. But when the King arrests the imposter, who strongly resembles Elizabeth’s missing brother, Prince Richard, his Tudor court is thrown into turmoil. Elizabeth must watch and wonder as her loyalty between family and crown is divided once more.

For Discussion

1. How would you describe the grief Elizabeth experiences in the aftermath of her uncle, Richard III’s death? What notable details about their relationship does her grief expose? How does Richard’s untimely demise imperil the future of the York line?

2.

“Henry Tudor has come to England, having spent his whole life in waiting…and now I am, like England itself, part of the spoils of war.”

Why does Elizabeth consider herself a war prize for Henry, rather than his sworn enemy for life? What role does politics play in the arrangement of royal marriages in fifteenth-century England?

3. Why are Maggie and Teddy of Warwick, the orphaned children of George, Duke of Clarence, in a uniquely dangerous position in the new court led by Henry Tudor? Why do Elizabeth and her family go to such great efforts to keep these York cousins away from Henry and his mother, Margaret, even though they know full well of their existence?

4. The mysterious disappearance of the young York princes, Richard and Edward, during their captivity in the Tower of London haunts all of the figures in

The White Princess.

What does the curse that Elizabeth and her mother cast on the boys’ presumed murderer reveal about their family’s belief in mysticism and witchcraft? How does the fact of this curse complicate Elizabeth’s dreams for her own offspring and their Tudor inheritance?

5.

“Daughter mine, you have known for all your life that you would be married for the good of the country and the advancement of your family. You will do your duty like a princess…and I expect you to look happy as you do it.”

Why is Elizabeth’s betrothal to Henry Tudor, the future king of England, an especially advantageous marriage for the York family? What might their union represent to England in the aftermath of the War of the Roses? To what extent does Henry’s decision to refuse his future bride and her family at his coronation suggest about his true feelings for the Yorks?

6. How does King Henry VII justify his rape of his betrothed, Elizabeth of York? To what extent is their impending marriage a union that he desires as little as she? Why does Henry’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, demand proof of Elizabeth’s fertility prior to their actual wedding? Why isn’t Elizabeth’s mother, Elizabeth Woodville, able to do more to protect her daughter from such violation?

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.