The dowager Duchess Cecily is seated on a great chair covered by a cloth of estate, and she does not trouble herself to rise to greet me. She is wearing a gown encrusted with jewels at the hem and the breast, and a large square headdress that she wears proudly, like a crown. Very well, I am her son’s wife but not yet an ordained queen. She is not obliged to curtsey to me, and she will think of me as a Lancastrian, one of her son’s enemies. The turn of her head and the coldness of her smile convey very clearly that to her I am a commoner, as if she herself had not been born an ordinary Englishwoman. Behind her chair are her daughters Anne, Elizabeth, and Margaret, dressed quietly and modestly so as not to outshine their mother. Margaret is a pretty girl: fair and tall like her brothers. She smiles shyly at me, her new sister-in-law, but nobody steps forward to kiss me, and the room is as warm as a lake in December.

I curtsey low, but not very low, to Duchess Cecily, out of respect to my husband’s mother, and behind me I see my mother sweep her grandest gesture and then stand still, her head up, a queen herself, in everything but a crown.

“I will not pretend that I am happy with this secret marriage,” the dowager duchess says rudely.

“Private,” my mother interrupts smartly.

The duchess checks, amazed, and raises her perfectly arched eyebrows. “I beg your pardon, Lady Rivers. Did you speak?”

“Neither my daughter nor your son would so far forget themselves as to marry in secret,” my mother says, her Burgundy accent suddenly revived. It is the very accent of elegance and high style for the whole of Europe. She could not remind everyone more clearly that she is the daughter of the Count of Saint-Pol, Burgundian royalty by birth. She was on first-name terms with the queen, whom she alone persists in calling Margaret d’Anjou, with much emphasis on the “d” of the title. She was the Duchess of Bedford by her first marriage to a duke of the royal blood, and the head of the Lancaster court when the woman seated so proudly before us was born nothing more than Lady Cecily Neville of Raby Castle. “Of course it was not a secret wedding. I was there and so were other witnesses. It was a private wedding.”

“Your daughter is a widow and years older than my son,” Her Grace says, joining battle.

“He is hardly an inexperienced boy. His reputation is notorious. And there are only five years between them.”

There is a gasp from the duchess’s ladies and a flutter of alarm from her daughters. Margaret looks at me with sympathy, as if to say there is no escaping the humiliation to come. My sisters and I are like standing stones, as if we were dancing witches under a sudden enchantment.

“And the good thing,” my mother says, warming to her theme, “is that we can at least be sure that they are both fertile. Your son has several bastards, I understand, and my daughter has two handsome legitimate boys.”

“My son comes from a fertile family. I had eight boys,” the dowager duchess says.

My mother inclines her head and the scarf on her headdress billows like a sail filled with the swollen breeze of her pride. “Oh, yes,” she remarks. “So you did. But of that eight, only three boys left, of course. So sad. As it happens, I have five sons. Five. And seven girls. Elizabeth comes from fertile royal stock. I think we can hope that God will bless the new royal family with issue.”

“Nonetheless, she was not my choice, nor the choice of the Lord Warwick,” Her Grace repeats, her voice trembling with anger. “It would mean nothing if Edward were not king. I might overlook it if he were a third or fourth son to throw himself away…”

“Perhaps you might. But it does not concern us. King Edward is the king. The king is the king. God knows, he has fought enough battles to prove his claim.”

“I could prevent him being king,” she rushes in, temper getting the better of her, her cheeks scarlet. “I could disown him, I could deny him, I could put George on the throne in his place. How would you like that-as the outcome of your so-called private wedding, Lady Rivers?”

The duchess’s ladies blanch and sway back in horror. Margaret, who adores her brother, whispers, “Mother!” but dares say no more. Edward has never been their mother’s favorite. Edmund, her beloved Edmund, died with his father at Wakefield, and the Lancastrian victors stuck their heads on the gates of York. George, his brother, younger again, and his mother’s darling, is the pet of the family. Richard, the youngest of all, is the dark-haired runt of the litter. It is incredible that she should talk of putting one son before another, out of order.

“How?” my mother says sharply, calling her bluff. “How would you overthrow your own son?”

“If he was not my husband’s child-”

“Mother!” Margaret wails.

“And how could that be?” demands my mother, as sweet as poison. “Would you call your own son a bastard? Would you name yourself a whore? Just for spite, just to throw us down, would you destroy your own reputation and put cuckold’s horns on your own dead husband? When they put his head on the gates of York, they put a paper crown on him to make mock. That would be nothing to putting cuckold’s horns on him now. Would you dishonor your own name? Would you shame your husband worse than his enemies did?”

There is a little scream from the women, and poor Margaret staggers as if to faint. My sisters and I are half fish, not girls; we just goggle at our mother and the king’s mother head to head, like a pair of slugging battle-axe men in the jousting ring, saying the unthinkable.

“There are many who would believe me,” the king’s mother threatens.

“More shame to you then,” my mother says roundly. “The rumors about his fathering reached England. Indeed, I was among the few who swore that a lady of your house would never stoop so low. But I heard, we all heard, gossip of an archer named-what was it-” She pretends to forget and taps her forehead. “Ah, I have it: Blaybourne. An archer named Blaybourne who was supposed to be your amour. But I said, and even Queen Margaret d’Anjou said, that a great lady like you would not so demean herself as to lie with a common archer and slip his bastard into a nobleman’s cradle.”

The name Blaybourne drops into the room with a thud like a cannonball. You can almost hear it roll to a standstill. My mother is afraid of nothing.

“And anyway, if you can make the lords throw down King Edward, who is going to support your new King George? Could you trust his brother Richard not to have his own try at the throne in his turn? Would your kinsman Lord Warwick, your great friend, not want the throne on his own account? And why should they not feud among themselves and make another generation of enemies, dividing the country, setting brother against brother again, destroying the very peace that your son has won for himself and for his house? Would you destroy everything for nothing but spite? We all know the House of York is mad with ambition; will we be able to watch you eat yourselves up like a frightened cat eats her own kittens?”

It is too much for her. The king’s mother puts out a hand to my mother, as if to beg her to stop. “No, no. Enough. Enough.”

“I speak as a friend,” my mother says quickly, as sinuous as a river eel. “And your thoughtless words against the king will go no further. My girls and I would not repeat such a scandal, such a treasonous scandal. We will forget that you ever said such a thing. I am only sorry that you even thought of it. I am amazed that you should say it.”

“Enough,” the king’s mother repeats. “I just wanted you to know that this ill-conceived marriage is not my choice. Though I see I must accept it. You show me that I must accept it. However much it galls me, however much it denigrates my son and my house, I must accept it.” She sighs. “I will think of it as my burden to bear.”

“It was the king’s choice, and we must all obey him,” my mother says, driving home her advantage. “King Edward has chosen his wife and she will be Queen of England and the greatest lady-bar none-in the land. And no one can doubt that my daughter will make the most beautiful queen that England has ever seen.”

The king’s mother, whose own beauty was famous in her day, when they called her the Rose of Raby, looks at me for the first time without pleasure. “I suppose so,” she says grudgingly.

I curtsey again. “Shall I call you Mother?” I ask cheerfully.

As soon as the ordeal of my welcome from Edward’s mother is over, I have to prepare for my presentation to the court. Anthony’s orders from the London dressmakers have been delivered in time, and I have a new gown to wear in the palest of gray, trimmed with pearls. It is cut low in the front, with a high girdle of pearls and long silky sleeves. I wear it with a conical high headdress that is draped with a scarf of gray. It is both gloriously rich and beguilingly modest, and when my mother comes to my room to see that I am dressed, she takes my hands and kisses me on both cheeks. “Beautiful,” she says. “Nobody could doubt that he married you for love at first sight. Troubadour love, God bless you both.”

“Are they waiting for me?” I ask nervously.

She nods her head to the chamber outside my bedroom door. “They are all out there: Lord Warwick and the Duke of Clarence and half a dozen others.”

I take a deep breath, and I put my hand to steady my headdress, and I nod to my maids-in-waiting to throw open the double doors, and I raise my head like a queen, and walk out of the room.

Lord Warwick, dressed in black, is standing at the fireside, a big man, in his late thirties, shoulders broad like a bully, stern face in profile as he is watching the flames. When he hears the door opening, he turns and sees me, scowls, and then pastes a smile on his face. “Your Grace,” he says, and bows low.

I curtsey to him but I see his smile does not warm his dark eyes. He was counting on Edward remaining under his control. He had promised the King of France that he could deliver Edward in marriage. Now everything has gone wrong for him, and people are asking if he is still the power behind this new throne, or if Edward will make his own decisions.

The Duke of Clarence, the king’s beloved brother George, is beside him looking like a true York prince, golden-haired, ready of smile, graceful even in repose, a handsome dainty copy of my husband. He is fair and well made, his bow is as elegant as an Italian dancer’s, and his smile is charming. “Your Grace,” he says. “My new sister. I give you joy of your surprise marriage and wish you well in your new estate.”

I give my hand and he draws me to him and kisses me warmly on both cheeks. “I do truly wish you much joy,” he says cheerfully. “My brother is a fortunate man indeed. And I am happy to call you my sister.”

I turn to the Earl of Warwick. “I know that my husband loves and trusts you as his brother and his friend,” I say. “It is an honor to meet you.”

“The honor is all mine,” he says curtly. “Are you ready?”

I glance behind me: my sisters and mother are lined up to follow me in procession. “We are ready,” I say, and with the Duke of Clarence on one side of me and the Earl of Warwick on the other, we march slowly to the abbey chapel through a crowd that parts as we come towards them.

My first impression is that everyone I have ever seen at court is here, dressed in their finest to honor me, and there are a few hundred new faces too, who have come in with the Yorks. The lords are in the front with their capes trimmed with ermine, the gentry behind them with chains of office and jewels on display. The aldermen and councillors of London have trooped down to be presented, the city fathers among them. The civic leaders of Reading are there, struggling to see and be seen around the big bonnets and the plumes, behind them the guildsmen of Reading and gentry from all England. This is an event of national importance; anyone who could buy a doublet and borrow a horse has come to see the scandalous new queen. I have to face them all alone, flanked by my enemies, as a thousand gazes take me in: from my slippered feet to my high headdress and airy veil, take in the pearls on my gown, the carefully modest cut, the perfection of the lace piece that hides and yet enhances the whiteness of the skin of my shoulders. Slowly, like a breeze going through treetops, they doff their hats and bow, and I realize that they are acknowledging me as queen, queen in the place of Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England, the greatest woman in the realm, and nothing in my life will ever be the same again. I smile from side to side, acknowledging the blessings and the murmurs of praise, but I find that I am tightening my grip on Warwick’s hand, and he smiles down at me, as if he is pleased to sense my fear, and he says, “It is natural for you to be overwhelmed, Your Grace.” It is, indeed, natural for a commoner but would never have occurred to a princess, and I smile back at him and cannot defend myself, and cannot speak.

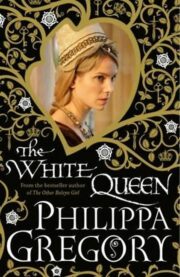

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.