“So, it is Queen Anne who puts you into his company, even into her own place, and the world sees this. Not Richard? Then what happens?”

“He says that he loves me,” she says quietly. She is trying to be modest, but her pride and her joy blaze in her eyes. “He says that I am the first love of his life and will be the last.”

I rise from my chair and go to the window and pull back the thick curtain so I can look out at the bright cold stars over the dark land of the Wiltshire down. I think I know what Richard is doing, and I don’t for one minute think that he has fallen in love with my daughter, nor that the queen is making gowns for her out of love.

Richard is playing a hard game with my daughter as pawn, to dishonor her, and me, and to make a fool of Henry Tudor, who has vowed to make her his wife. Tudor will hear-as quickly as his mother’s spies can take ship-that his bride to be is in love with his enemy and is known throughout the court as his mistress while his wife looks on smiling. Richard would do this to damage Henry Tudor even though he dishonors his own niece. Queen Anne would be compliant rather than stand up to Richard. Both Neville girls were boot-scrapers to their men: Anne has been an obedient servant from the first day of her marriage. And besides, she cannot refuse him. He is King of England without a male heir, and she is barren. She will be praying that he does not put her aside. She has no power at all: no son and heir, no baby in the cradle, no chance of conception; she has no cards to play at all. She is a barren woman with no fortune of her own-she is fit for nothing but the nunnery or the grave. She has to smile and obey; protests will get her nowhere. Even helping in the destruction of my daughter’s reputation will probably earn Anne nothing more than an honorable annulment.

“Has he told you to break off your betrothal to Henry Tudor?” I ask her.

“No! It’s nothing to do with that!”

“Oh.” I nod. “But you can see that this will be a tremendous humiliation for Henry Tudor when the news gets out.”

“I would never marry him anyway,” she bursts out. “I hate him. I believe it was he who sent the men to kill our boys. He would have come to London and taken the throne. We knew that. That’s why we called down the rain. But now…but now…”

“Now what?”

“Richard says that he will put Anne Neville aside and marry me,” she breathes. Her face is alight with joy. “He says that he will make me his queen and my son will sit on my father’s throne. We will make a dynasty of the House of York, and the white rose will be the flower of England forever.” She hesitates. “I know you cannot trust him, Lady Mother, but this is the man I love. Can you not love him for my sake?”

I think that this is the oldest, hardest question between a mother and her daughter. Can I love him for your sake?

No. This is the man who envied my husband, who killed my brother and my son Richard Grey, who seized my son Edward’s throne and who exposed him to danger, if nothing worse. But I need not answer the truth to this my most truthful child. I need not be open with this most transparent child. She has fallen in love with my enemy, and she wants a happy ending.

I open my arms to her. “All I ever wanted was your happiness,” I lie. “If he loves you and will be true to you, and you love him, then I want nothing more.”

She comes into my arms and she lays her head on my shoulder. But she is no fool, my daughter. She lifts her head and smiles at me. “And I shall be Queen of England,” she says. “At least that will please you.”

My daughters stay with me for nearly a month, and we live the life of an ordinary family, as Elizabeth once wanted. In the second week it snows, and we find Nesfields’ sleigh and harness up one of the cart horses and make an expedition to one of the neighbors, and then find the snow has melted and we have to stay the night. The next day we have to trudge home in the mud and the slush as they cannot lend us horses and we take turns to ride bareback on our own big horse. It takes us the best part of the day to get home and we laugh and sing all the way.

In the middle of the second week there is a messenger from court and he brings a letter for me, and one for Elizabeth. I call her to my private chamber, away from the girls, who have invaded the kitchen and are making marchpane sweetmeats for dinner, and we open our letters at either end of the writing table.

Mine is from the king.

I imagine Elizabeth will have spoken with you about the great love I bear her, and I wanted to tell you of my plans. I intend that my wife shall admit she is past the years of childbearing and take residence in Bermondsey Abbey and release me from my vows. I will seek the proper dispensations and then marry your daughter and she will be Queen of England. You will take the title of My Lady, the Queen’s Mother, and I will restore to you the palaces of Sheen and Greenwich on our wedding day, with your royal pension. Your daughters will live with you and at court, and you shall have the arranging of their marriages. They will be recognized as sisters to the Queen of England and of the royal family ofYork. If either of your sons has been in hiding and you know of his whereabouts, then you may now send for him in safety. I will make him my heir until Elizabeth gives birth to my son. I will marry Elizabeth for love, but I am sure you can see that this is the resolution of all our difficulties. I hope for your approval, but I will proceed anyway. I remain your loving kinsman. RR

I read the letter through twice and I find a grim smile at his dishonest phrasing. “Resolution of all our difficulties” is, I think, a smooth way of describing a blood vendetta which has taken my brother and my Grey son, and which led me to foment rebellion against him and curse his sword arm. But Richard is a York-they take victory as their due-and these proposals are good for me and mine. If my son Richard can come home in safety and be a prince once more at the court of his sister, then I will have achieved everything that I swore to regain, and my brother and my son will not have died in vain.

I glance down the table at Elizabeth. She is rosy with blushes and her eyes are filled with luminous tears. “He proposes marriage?” I ask her.

“He swears that he loves me. He says he is missing me. He wants me back at court. He asks you to come with me. He wants everyone to know that I will be his wife. He says that Queen Anne is ready to retire.”

I nod. “I won’t go while she is there,” I say. “And you may go back to court but you are to behave with more discretion. Even if the queen tells you to walk with him, you are to take a companion. And you are not to sit in her place.”

She is about to interrupt, but I raise my hand. “Truly, Elizabeth, I don’t want you being named as his mistress, especially if you hope to be his wife.”

“But I love him,” she says simply, as if that is all that matters.

I look at her and I know my face is hard. “You can love him,” I say. “But if you want him to marry you and make you his queen, you will have more to do than simply loving.”

She holds his letter to her heart. “He loves me.”

“He may do, but he will not marry you if there is a whisper of gossip against you. Nobody gets to be Queen of England by being lovable. You will have to play your cards right.”

She takes a breath. She is no fool, my daughter, and she is a York through and through. “Tell me what I have to do,” she says.

FEBRUARY 1485

I bid my daughters farewell on a dark day in February and watch their guard trot off through the mist that swirls around us for all of the day. They are out of sight in moments, as if they had disappeared into cloud, into water, and the thud of the hoofbeats is muffled and then silenced.

The house seems very empty without the older girls. And in missing them, I find my thoughts and my prayers go to my boys, my dead baby George, my lost boy Edward, and my absent boy Richard. I have heard nothing of Edward since he went into the Tower, and nothing of Richard since that first letter when he told me he was doing well and answering to the name Peter.

Despite my own caution, despite my own fears, I start to hope. I start to think that if King Richard marries Elizabeth and makes her his queen I will be welcomed at court again, I will take up my place as My Lady, the Queen’s Mother. I will make sure that Richard is trustworthy, and then I will send for my son.

If Richard is true to his word and names him as his heir, then we will be restored: my son in the place he was born to, my daughter as Queen of England. It will not have come out as Edward and I thought it would when we had a Prince of Wales and a Duke of York and we thought, like young fools, that we would live forever. But it will have come out well enough. If Elizabeth can marry for love and be Queen of England, if my son can be king, after Richard, then it will have come out well enough.

When I am at court, and in my power, I shall set men to find the body of my son, whether it is under the convenient stair-as Henry Tudor assures us-or buried in the river, as he corrects himself, whether it has been left in some dark lumber room, or is hidden on holy ground in the chapel. I shall find his body, and trace his killers. I shall know what took place: whether he was kidnapped and died by accident in the struggle, whether he was taken away and died of ill health, whether he was murdered in the Tower and buried there, as Henry Tudor is so very certain. I shall learn of his end, and bury him with honor, and order Masses for his soul to be said forever.

MARCH 1485

Elizabeth writes to me briefly of the queen’s worsening health. She says no more-she need say no more-we both realize that if the queen dies, there will be no need for an annulment or the settlement of Queen Anne in an abbey; she will be out of the way in the easiest and most convenient way possible. The queen is afflicted with sorrows, she weeps for hours without cause, and the king does not come near her. My daughter records this as the queen’s loyal maid-in-waiting and does not tell me if she slips from the sick chamber to walk with the king in the gardens, if the buttercups in the hedgerow and the daisies on the lawn remind her and him that life is fleeting and joyful, just as they remind the queen that it is fleeting and sad.

Then one morning in the middle of March I awake to a sky unnaturally dark, to a sun quite obscured by a circle of darkness. The hens won’t come out of their house; the ducks put their heads under their wings and squat on the banks of the river. I take my two little girls outside and we wander uneasily, looking at the horses in the field who lie down and then lumber up again, as if they don’t know whether it is night or day.

“Is it an omen?” asks Bridget, who of all of my children seeks to see the will of God in everything.

“It is a movement of the heavens,” I say. “I have seen it happen with the moon before, but never with the sun. It will pass.”

“Does it mean an omen for the House of York?” Catherine echoes. “Like the three suns at Towton?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “But I don’t think any of us are in danger. Would you feel it in your heart, if your sister was in trouble?”

Bridget looks thoughtful for a moment then, prosaic child, she shakes her head. “Only if God spoke to me very loud,” she says. “Only if He shouted and the priest said it was Him.”

“Then I think we have nothing to fear,” I say. I have no sense of foreboding, though the darkened sun makes the world around us eerie and unfamiliar.

Indeed, it is not for three days that John Nesfield comes riding to Heytesbury with a black standard before him and the news that the queen, after a long illness, is dead. He comes to tell me, but he makes sure to spread the news throughout the country, and Richard’s other servants will be doing the same. They will all emphasize that there has been a long illness, and the queen has at last gone to her reward in heaven, mourned by a devoted and loving husband.

“Of course, some say she was poisoned,” Cook says cheerfully to me. “That’s what they’re saying in Salisbury market, anyway. The carrier told me.”

“How ridiculous! Who would poison the queen?” I ask.

“They say it was the king himself,” Cook says, putting her head to one side and looking wise, as if she knows great secrets of the court.

“Murder his wife?” I ask. “They think he would murder his wife of a dozen years? All of a sudden?”

Cook shakes her head. “They don’t have a good word to say of him in Salisbury,” she remarks. “They liked him well enough at first and they thought he would bring justice and fair wages for the common man, but since he puts northern lords over everything-well, there’s nothing they would not say against him.”

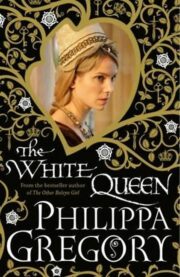

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.