Alix said that only Kings and Queens had crowns but a tiara would be very nice. But nine-year-old Thyra thought a crown would be best.

‘You’ll have to wait until the old Queen dies,’ she said. ‘Then you’ll get your crown.’

‘Oh, don’t talk about her dying,’ cried Alix.

‘Is it unlucky?’

‘I don’t know but I met her, you know, and in a way … I quite liked her. Besides, I should be terrified to be Queen. Princess of Wales will do very nicely for a start.’

Dagmar regarded her sister with solemn eyes. Thyra didn’t seem to realise that this was going to be the break-up of the family. In future when they went out riding or played their games or packed up for the summer visits to Rumpenheim, Alix would not be with them. Nothing would be the same again; and then very soon she herself might go away … perhaps to Russia.

Everyone was so excited and said it was such good fortune, but losing Alix from the family circle seemed just the opposite to Dagmar.

The Queen was sending despotic messages from Windsor. The wedding should take place in January. She saw no reason for delay.

‘Good Heavens,’ cried Louise, ‘she cannot dictate to us in this way. Imagine poor Alix leaving at that time of the year. The ports would doubtless be frozen up in any case. Besides, it is for us to say when the wedding shall be. January is far too soon.’

The Queen wrote back. She granted that the weather might prevent Alix’s coming in January, but her daughter Alice was due to have her baby in February and as it was Alice’s first and the confinement was to take place at Windsor, that made February out of the question.

March was agreed upon.

Uncle Leopold, not to be left out of the excitement, suggested that Alix should stay a few days in Brussels en route for England. It would give her a respite which would be much needed. It would also give Leopold an opportunity of grounding her in what he would expect of her when she was Princess of Wales. He would want to remind her that he had played his part in bringing about this brilliant marriage, also that he was the favourite uncle of the Queen and his opinions carried some weight with her.

The arrangements were finally agreed to and the deputations began to arrive at the Yellow Palace. All day long people were calling from the foreign embassies; the tradesmen came too and there were long speeches to be listened to, gifts to be accepted, elaborate and humble. The shoemakers of Copenhagen presented the Princess with a pair of gold embroidered shoes and the villagers of Bernstorff gave her porcelain vases in a wicker basket tied with ribbons in the colours of the flags of Denmark and England. These small gifts touched her more deeply than the diamond and pearl necklace given by the King.

The Queen wrote that she was presenting the bride with a wedding gown of Honiton lace and it was already being made for her. It would be one of her wedding presents to the Princess, to whom she always referred as dear sweet Alix, which confirmed the belief that Alix had made an unusually good impression on her.

The dark February days seemed to grow shorter and shorter. Poor Dagmar was very despondent and Alix knew that she herself was going to feel the separation deeply, but she had Bertie to comfort her while Dagmar had only her hopes – or fears – of the Russian alliance.

Each day the Rev. M. S. Ellis, who was Chaplain to the British Legation in Copenhagen, came to the Yellow Palace to instruct her in the form of Protestantism which was practised in England and was slightly different from the Lutheranism of Denmark.

Then there were the balls and receptions given in her honour. Wally’s husband – now Sir Augustus – gave a ball for her at the British Embassy. Wally was more vivacious than ever and obviously delighted that her efforts had borne fruit. She whispered to Alix that she looked beautiful and Bertie was going to be very proud of her. And Wally of course would pay frequent visits to England. ‘Don’t forget I’m married to an Englishman,’ she said with a grimace towards her handsome husband.

Alix’s grandparents gave a party for her and her grandfather was clearly delighted with her.

‘Such an ugly little thing you were when you were born,’ he kept reminding her.

Then of course there was the reception at the Yellow Palace when she must say good-bye to all those who had taught her and served her during her childhood. This was the saddest of them all.

Dear Miss Knudsen, who had taught her English and had become a friend, was very sad. Alix knew that she owed a great deal to her because under her tuition her English had become quite good. She had only the faintest accent which Bertie assured her was adorable and now and then she used expressions which might not have been exactly English but which she realised were quaint and charming.

Then came the last night in the Yellow Palace. Dagmar stayed late in her room and they sat talking of the past. Poor Dagmar, who was going to be lonely and was a little apprehensive. Dagmar was far cleverer than she was. Louise had always said so. Alix was not the clever one in the family, even though she might be the beauty.

‘You were always so much quicker at lessons than I,’ she told Dagmar to cheer her. ‘When you marry you’ll have nothing to fear. You will understand politics and everything. I’m lucky. Bertie told me he was glad I was not one of those clever women. He couldn’t abide them. Suppose he had been like his father. I would never have done.’

‘There aren’t many men like him, I suppose.’

‘According to the Queen, alas – according to Bertie, thank heaven – No!’

‘Bertie is a little disrespectful towards his dear papa.’

‘Bertie is honest. And I think he is much nicer than his saintly papa.’

‘I’m sure of that,’ said Dagmar.

Then they talked of tomorrow and the journey and the wedding. It was all so exciting.

‘I’m sure I shall never sleep tonight,’ said Alix.

But Dagmar said she would and kissing her good night went rather sorrowfully to her own room.

Alix tried to turn her attention to The Heir of Redclyffe which Miss Knudsen had lent her and which she said would improve her English. She must finish it because she must give it back to Miss Knudsen before she left for England.

Alix woke in her little room in the Yellow Palace on the 28th of February 1863 and the first thing she thought was: ‘I shall never sleep in this room again.’

She looked about it at the piano, the cabinet and the work table and remembered how when she had returned from her confirmation her mother had brought her up here and told her that now she was grown up she should have a room of her own. How important that had seemed! She had felt then that she had come to the greatest turning point in her life. But what was that compared with this?

Louise came in.

‘Well, my dear, this is the day and there is a great deal to do.’ She smiled wryly. ‘You must not be late in leaving.’

‘We are not to leave until this afternoon.’

‘No, but there is plenty to do before that.’

She was right; the morning was gone before she was ready for it, and then the carriages which would take them to the railway station were at the door.

The family were clustered round her. She was thankful that this was not the final farewell for they were all accompanying her to England for the ceremony; even little Valdemar was to come with them. He was only four and, although the ceremony would mean little to him, could not be left at home.

The streets of Copenhagen were crowded. The English marriage had been the main topic of conversation throughout the whole of Denmark ever since the Princess had gone to England and won the approval of the Queen. The English match was the best possible thing for Denmark which would be allied to that most powerful country through marriage; and with Prussian threats beginning to menace that was a very comforting thought. So there were cheers for the elegant girl who had given them this comfort; and how proud they were of her, for she looked very elegant in a brown silk dress with white stripes and a little bonnet perched on her head. Flowers were thrown at the carriage as it passed and people crowded round it so that at one time it seemed as though they would be unable to move. This was a loving demonstration and Alexandra was deeply moved by it.

All the same it was a relief to settle into the train. Christian and Louise smiled approvingly at their daughter.

‘The first stage is over,’ said Christian, ‘and may I say you did very well, my dear.’

‘Oh, that part was easy,’ said Alix with a smile.

‘They are such loyal good people,’ added Louise.

‘Well, they’ve known me all my life,’ Alix reminded her. ‘They will have seen me perhaps walking along the Lange Linie and gazing into the shops and wondering whether I could copy the dresses there.’

‘It will be different now,’ said Louise. ‘Dagmar and Thyra will have to carry on, though, for a while.’

‘It won’t be the same without Alix,’ said Dagmar quietly. ‘She always knows how a dress is going to look before it’s made.’

‘We’re going to miss our Alix,’ said Christian sadly.

‘Now, Papa,’ reproved Louise, ‘don’t let us be morbid.’

She called attention to Valdemar who was talking to his new toy donkey and showing him the countryside they were passing through.

‘Isn’t this a great adventure, Valdy darling?’ said Alix.

Valdemar nodded. ‘Donkey likes trains,’ he said.

‘And you, Valdy dear, what do you like?’

He thought for a while and then he said, ‘I like Donkey.’

And the happy domestic atmosphere seemed to have come back to them.

There were receptions everywhere they stopped, even in Germany which was strange because the Germans were somewhat put out by the match. English royalty usually married Germans; English royalty was half German. The Germans felt this departure from an old custom and taking in Denmark was to some extent a slight on their princesses. But Alexandra was young and charming and whatever the statesmen thought the people could not resist a beautiful bride.

At the Laeken Palace Uncle Leopold was waiting to welcome them.

He embraced Alix warmly, and called her his dear child. He was so happy about this match. It was the best thing possible for Bertie and for Alix – his dear, dear children. ‘I’m as happy now as when Victoria married Albert,’ he told Alix, ‘my niece and my nephew but to me they were like daughter and son, as you two young people are. I have suffered such pain these last weeks. My doctors told me I should have stayed in bed. “In bed,” I said, “when my dearest Alexandra is coming to visit me en route for England for her marriage with that other dear child of mine!” Whatever pain I had to suffer I was not going to stay in bed.’

He hobbled round effectively now and then giving a little grimace to indicate how bad the pain was but Uncle Leopold so obviously enjoyed his ailments that his calling attention to them added nothing sombre to the occasion, for with his painted cheeks, his built-up shoes to make him look taller, and his pleasant wig, he still retained signs of the singularly handsome man he had been in his youth.

He had promised himself many little chats with Alexandra. He knew so much about the English Court and way of life that he wanted to give her the benefit of his knowledge. If she were in any difficulty at any time she would know that all she had to do was to write to him.

Alix listened charmingly. She was sure, she said, that she would never learn anything about politics. They were so complicated.

‘You must remember that you will have a certain influence with your husband, my dear child. And he will become more and more important, particularly if the Queen remains in seclusion as she has since the Consort’s death. You could have a part to play. Always remember your own country and your own good friends. The stability of Denmark … and Belgium … is very necessary to European peace. I should not like to see that threatened or it could mean great trouble. Always remember that if you are bewildered about anything, you can always write to me for advice. I will be to you what I was to the Queen in the days when she needed me.’

Alix thanked him, but she was determined not to meddle in politics. She was sure Bertie would not like it.

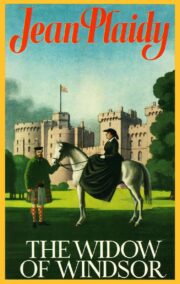

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.