It was very pleasant to have talks with Vicky. Somehow she could talk more freely to her eldest daughter than to the others. Vicky was such a woman of the world. Alice for all her married state still seemed innocent and unworldly. She could discuss having children, female ailments and feelings with Vicky. Vicky had a wisdom which the others were not old enough or not experienced enough to share; and although she could discuss with Alice Mr Gilbert Scott’s proposal for a magnificent Memorial to be set up in Kensington to dear Albert, to Vicky she could talk of Affie’s affair and his obvious love of the gay life and Bertie’s life with Alix, for the Queen was well aware that Bertie was leading a life of his own in some of the gayer clubs while Alix stayed at home.

Trouble seemed to be never far off, both in domestic and foreign affairs; and with such a family as hers, the two were often unhappily combined.

Alice came in to suggest they go for a drive to Clova. ‘It would do you good, Mama,’ said Alice.

The Queen sighed. ‘It was always one of Beloved Papa’s favourite spots.’

‘Grant won’t be able to come with us as he is with Vicky in Abergeldie.’

‘My dear child, we can well do without Grant. Remember we have Brown.’

‘Oh yes, Mama, I believe you feel safer with him than with any of the others.’

‘He’s a good faithful soul.’

‘Inclined to forget his place, Mama, at times, don’t you think?’

‘Brown never forgets his place, which is to protect me. I can tell you, Alice, that I would well dispense with the bowing and sycophantic greetings and addresses I get from some people. I, as Beloved Papa did, always prefer sincerity.’

‘Well, Brown will accompany us to Clova. I will go and tell Lenchen that you wish to go. What do you think – about half past twelve?’

‘That would be very suitable, my love.’

Dear Alice! she thought. She does not look really well. I don’t think she is very strong. Such a comfort, though. And Louis is rather helpless. It’s very sad he can’t provide a home for Alice. Poor Alice, she had not been so well since her confinement. A very sad time. Dear little Victoria Alberta – the Queen was very pleased with those names – had been born in Windsor Castle in the same bed which the Queen had used in confinements and Alice had actually worn the same shift which her mother used for all her children. It had been such a trying time because dear Alice looking so wan had resembled Beloved Papa when he was on his deathbed; and when Louis had come in and been so tender and loving and embraced dear Alice she had suddenly seen herself and Albert after the birth of one of the children; and it was all very hard to bear.

She would send for Annie MacDonald and prepare herself for the drive, although she didn’t really need Annie as much as she used to because Brown seemed to have taken charge even of her clothes. Sometimes he would chide her because he considered her cloak too thin. ‘The mist’ll get right through to your bones, woman,’ he would say in his dear blunt way which showed that he was careless of whether he offended her because his main concern was her health. The dear, good, faithful creature! Albert had always been so amused by his rough ways.

They were ready to depart at twelve, just herself, Alice and Lenchen. The younger ones were doing lessons with Tilla, Miss Hildyard who had been with them for so long and was such a dear good creature.

Lenchen was fussing about luncheon because they were taking some broth with them and some potatoes ready to boil. There was absolutely no need to fuss. Brown would take care of everything. It would be dark when they came back but Albert had always enjoyed night driving and as he had said with Grant and Brown they were perfectly safe.

Smith the coachman was driving and Brown was on the box beside him and Willem, Alice’s little Negro boy-servant, was standing up behind.

How she loved the dear hills and glens where she had walked so often with the Beloved Being; there was something to remind her everywhere. She was telling Alice and Lenchen how she used to take out her book and sketch while Papa went shooting and the children used to ride on their ponies.

‘We remember, Mama,’ said Lenchen patiently. ‘We were there, you know.’

Alice looked gently reproving but none of the children had Alice’s sympathetic ways.

It was very pleasant to stop at Altnagiuthasach where the efficient Brown warmed the broth and boiled the potatoes. ‘What a long time they take to boil,’ said the Queen to which Brown replied: ‘Ye’ll nae be wanting them half cooked, so have a wee bit of patience.’ At which Alice blenched but the Queen just smiled at another manifestation of Brown’s stalwart protection.

How good the broth and potatoes tasted when they were ready. ‘Worth waiting for,’ said Brown with reproach in his voice for his impatient mistress.

‘Well worth waiting for,’ agreed the Queen, for in spite of her sorrow she could always enjoy her food. She recalled happy picnics of the past when Dear Papa had been so hungry and declared that nothing tasted as good as John Brown’s broth and boiled potatoes eaten on the moors.

With great efficiency Brown had the plates and dishes washed in a burn and stored away and soon they were on their way again. And there were the snow-tipped Clova Hills, breathtakingly beautiful.

‘I hope you girls appreciate this wild beauty. Beloved Papa was especially fond of it.’

Her daughters assured her that Clova was one of their favourite spots too. But, said Alice, wasn’t it time that they started to return? They would be very late as it was and there had been one or two flurries of snow.

The Queen smiled at the kilted figure of her faithful Highlander. All would be well, she assured her daughter.

But this was not quite true. It had grown dark and Brown had lighted the lamps; and as they drove along, the carriage gave a lurch and she realised they were off the road. She could hear Brown’s remonstrating with Smith, who had evidently taken a wrong turning. Brown descended and taking a lantern, walked ahead of the carriage holding the light high.

‘Whatever has happened to Smith?’ cried Alice. ‘He should be able to see the road very well.’

Poor Smith, thought the Queen, he was getting old. He had been driving them for thirty years. He really must be persuaded that he was too old for the task. A fine discovery to make at nightfall on one of the roads through the Highlands! She was thankful that Brown was with them.

Suddenly the carriage tilted to one side.

Alice took the Queen’s hand and held it firmly. ‘I think … we’re upsetting,’ she cried.

She was right. At that moment the carriage had overturned; the Queen had been tipped out and was lying face down on the ground. The horses were down and Lenchen cried out in terror.

Brown was bending over the Queen.

‘The Lord have mercy on us!’ he cried. He lifted the Queen in his arms. ‘Are you all right, woman?’ he asked.

‘I … I think so,’ said the Queen.

‘Lord be praised for that,’ he said and the sincerity in his voice brought tears to the Queen’s eyes.

‘See to the Princesses,’ she said.

‘All in good time,’ replied Brown.

Alice and Lenchen, who were not hurt, very soon were helped to their feet. Alice’s clothes were torn and dirty and Lenchen threw herself at her mother begging to be told that no harm had come to her.

The Queen assured her daughters that she was all right but she could feel that her face was sore, and touching it carefully realised that it was swollen; her right thumb was swelling rapidly and was very painful but as no good purpose could be served at this stage by mentioning it, she said nothing.

Smith seemed very confused and naturally Brown took charge of the situation.

‘It’s good luck I’m with ye,’ he muttered and said he wanted someone to hold the lamp while he cut the traces. Poor Smith was distraught and useless so Alice held the lantern and very soon the efficient Brown had the horses up. He was relieved, he said, that they were not hurt and there was only one thing to do. He was going to send Smith off for another carriage and he was staying with them to make sure no harm befell them.

‘Dear good Brown,’ murmured the Queen.

They sat as best they could in the shelter of the overturned carriage and Brown brought a little claret for them. Brown could always be relied upon to produce wine and spirits when they were needed.

‘Mama, how long will it take for them to bring another carriage?’ asked Lenchen.

‘I don’t know, my love, but as Beloved Papa always said we must make the best of any situations in which we find ourselves.’

Brown drank liberally of the claret which shocked Alice but the Queen thought he thoroughly deserved any reward, for what would have happened without him she could not imagine.

‘Smith is too old to drive us,’ said the Queen. ‘This is the last time he shall do so. We should have realised it before. These good faithful servants go on and we are inclined to forget that they become too old for service.’

‘I’ll not have him drive you again,’ murmured Brown.

The Queen smiled and began to talk of how the Prince had always enjoyed drives in the Highlands, particularly at night when he said they became even more like the Thuringenwald.

‘I suppose because you couldn’t see so clearly,’ said Lenchen, which made the Queen frown.

‘Eh, now listen,’ said Brown suddenly when the Queen was talking of how Papa had always presented her with the first sprig of heather he picked each year.

‘Sound of horses,’ said Brown. ‘Someone’s coming this way.’

To the delight of the party it turned out to be Kennedy, another of the grooms who, fearing that some accident had happened since they were so long in returning to the Castle, had come out with the ponies to look for them.

How very thoughtful! said the Queen. Albert had always said what a good servant Kennedy was and Albert as usual was right.

So they were able to leave at once and only when they arrived at Balmoral did the Queen see how bruised her face was. There was something very wrong with her thumb too.

She was so exhausted that she wished to retire at once to her room and ordered that a little soup and fish be sent to her.

She was soon fast asleep but in the morning realised that she had a rather black eye and her thumb really felt as though it were out of joint.

There was a great deal of fuss about the accident. Vicky and Fritz came over to Balmoral to inquire how the party had survived. The Queen’s bruises were greeted with horror and the doctors were attending to her thumb, which they feared had been put out of joint.

The Queen brushed it all aside and when she returned to London Lord Palmerston took her to task for endangering her safety by driving at night through wild country.

‘My dear Lord Palmerston,’ she said, ‘I have good and trusty servants. I can rely on them absolutely.’

‘Begging Your Majesty’s pardon, I must point out that they did not prevent the overturn of your carriage.’

‘Accidents will always happen, but there was no alarm whatsoever. John Brown behaved with absolute calm and efficiency. I do assure you, Lord Palmerston, that I feel safer driving through the Highland lanes by night than I have sometimes felt on Constitution Hill in broad daylight.’

‘There have been most regrettable isolated incidents, M’am, and these have happened to other sovereigns because there are certain madmen in the world; but the hazards faced on poor tracks in mountainous country could be avoided, and I, with the backing of your Majesty’s ministers, would ask you to desist from placing yourself in danger.’

‘Nonsense,’ said the Queen. ‘The Prince Consort delighted in driving at night. It never occurred to him that there was any danger, and I am sure if there had been he would have been the first to be aware of it. He was always solicitous for my safety.’

She was an obstinate woman, thought old Pam; and with the backing of the defunct Prince Consort she was immovable; so there was no point in wasting further time on that subject. They must let her continue with her night drives and be thankful for the Prince of Wales who was taking on far more of the royal duties than the Sovereign herself.

The Prince and Princess of Wales had taken a great fancy to Sandringham. It was Bertie’s pleasure to bring with him friends from London to pass a very gay week or so in this royal residence which had never held the same place in the Queen’s affections as Osborne or Balmoral. Perhaps, he said with a grimace, this was what he liked so much about it. It seemed at Osborne and Balmoral that his father still lived on; everywhere in those houses his influence was apparent. It was quite different at Sandringham.

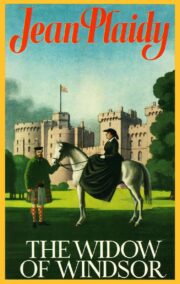

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.