‘But, Mama, I cannot understand what she has done to make you so angry.’

‘She refused to shake hands with Brown … to his face. She said you had forbidden her to be too familiar with servants.’

‘But, Mama, I have forbidden her and Brown is a servant, and she was absolutely right to refuse.’

‘Papa and I brought up you children to show tact and charm to everyone … the highest and the lowest. And I would have you know that I told her to shake hands and she disobeyed me. Did you bring her up to disobey her grandmother and the Queen?’

‘Of course not, Mama.’

‘Well, that is what she did.’

‘The children have always been made aware of your position, Mama, but I and Fritz have always been very anxious to instil in them not to be familiar with servants. That can be very dangerous.’

‘Brown is not an ordinary servant.’

‘We know that well, Mama.’

‘And I will not have him treated as such. During my illness he has been my great comfort. I get precious little from some of you children.’

‘Poor Charlotte,’ went on Vicky. ‘It is a little difficult for her, you know. You would not have her mixing with the servants, I’m sure; and yet she is supposed to treat Brown as though he is … the Prime Minister at least.’

‘That is a ridiculous statement. Brown has never been treated as the Prime Minister. Brown is a very good friend. Papa noticed him and singled him out for special service.’

‘For service, yes,’ said Vicky.

‘And very good service he gives.’

‘We none of us have doubted that, Mama, but you must be aware that there is a good deal of comment concerning Brown’s position in your household and surely in view of the present unrest everywhere even you must be aware that this is not a good thing.’

‘Even I? Are you suggesting that I am less aware of what is going on than others!’

‘You do shut yourself away, Mama, and you must admit the people are getting very restive and there is a certain uneasiness. Mr Gladstone …’

‘Pray don’t talk to me about that man.’

‘He is your Prime Minister, Mama.’

‘It was never my wish that he should be.’

‘But it is the people’s wish.’

The Queen was angry. How dared her daughter presume to dictate to her! This was intolerable. She began to speak; she talked of the lack of sympathy she received from her children. Alfred and Vicky should have been a comfort to her and what happened? They came down and tried to disturb her household. Since Dearest Papa had died where could she turn for comfort? Because she had a good servant they would like to take him away from her. She had had a sympathetic Prime Minister and in a few months time he was replaced by Mr Gladstone. She felt ill and lonely. Her grandchildren disobeyed her; her children conspired to disrupt her household. She would be rather glad to be lying in the mausoleum at Frogmore beside the only one who had ever really cared for her.

Vicky said: ‘Mama, pray do not distress yourself so …’

‘Pray refrain from giving me your unwanted advice. I wish to be alone.’

‘Mama …’

The Queen regarded her daughter stonily. ‘Surely you heard me express my wish?’

‘Yes, Mama,’ said Vicky with resignation.

‘And send Brown. I will take a little whisky. And then I shall rest.’

There was no way of warning Mama, thought Vicky. This absurd situation with Brown was growing worse rather than improving. He seemed now to be more important than the Queen’s own family.

But there was nothing to be done. That was the way the Queen wanted it and the Queen’s words were law, at least in the family.

Was there no end to trouble? What Does She Do With It? was being circulated all over the place. Royal popularity was at its lowest when one of the more radical members of Parliament, Sir Charles Dilke, made a speech which was a direct attack on the Queen. She failed in her duty, he pointed out; she lived in seclusion at Windsor, Balmoral or Osborne; she only appeared in public at times when she wanted Parliament to vote money for her family; she had a vast income and on what did she spend it? Was she hoarding it? Wasn’t it meant to be spent on ceremonies and State occasions? What was the point of having a Queen who never appeared in public? It would be much less expensive and more to the point to replace royalty by a republic.

The Queen was fuming with rage when she read the report of the speech.

Who was this man Dilke? He should be ostracised. She hoped she would never be asked to meet him. He was obviously a scoundrel.

Mr Gladstone was upset. He was soon on with the old theme. If she would only come out of retirement … if she would be seen in London … it would make all the difference. It was true that she was in communication with her ministers, that she worked on state papers, but a Queen must not only do her duty, she must be seen to do it.

‘I shall do as I wish,’ she said. ‘Those who think that I shall be frightened by this man Dilke have made a very grave mistake.’

She refused to brood on it. It was getting near the end of the year and there was one day which she dreaded more than any other, the 14th of December, the day when Albert had died. Ever since that day ten years ago his memory had been kept fresh; every year when the 14th came round she stayed alone in her room and thought of him and then went to the mausoleum and meditated on his virtues and the great loss his going had brought her.

She was brooding on this when a letter arrived from Alice who was staying with her children at Sandringham with Bertie and Alix.

Sandringham, thought the Queen. Bertie and Alix were too often there, and by all accounts giving very gay parties. Bertie liked to entertain and the entertainments there were said to be lavish. She was concerned by his love of the gay life and Alix could not like it either. She believed, though, that Bertie had a little to vex him in Alix’s way of never being at a place on time. Bertie had ordered that all the clocks at Sandringham should be half an hour fast so that Alix should be helped to keep her appointments. How ridiculous! Alix would soon discover that the clocks were fast and be as late as ever. The Queen disliked clocks to be fast. ‘After all,’ she said, ‘it is a lie.’

She was glad that Alice was at Sandringham. There was something very gentle about Alice and she and Alix had become such good friends.

‘It’s the first time in eleven years that I have spent Bertie’s birthday with him,’ wrote Alice. ‘Bertie and Alix are so kind and give us such a warm welcome showing how they like having us …’

Oh yes, it was good for the children to be together and although the girls had married abroad they could come home fairly frequently. It must be very pleasant for Alice to be in England for that poor Louis of hers was not so comfortably off as one would have liked.

I hope I was right to agree to the marriage. What would Albert have done? This was the Albert season and she sat brooding on that terrible time when he had gone to Cambridge in dreadful weather and come home to her so ill.

There was no one like him. There never would be, Blessed Angel that he was. How fortunate she had been to have twenty years of her life with him – but having known such perfection it was harder to bear his loss.

She heard that Bertie had gone up to Scarborough to Lord Londesborough’s place accompanied by Lord Chesterfield. Alix had stayed behind. The Queen could imagine what gay parties there would be up there. Oh dear, how different he was from Dearest Albert!

A week or so later there was disturbing news. The Prince of Wales had left Scarborough and was at Marlborough House and Lord Chesterfield had been taken very ill. A few days later the Prince was ill.

Bertie left London because he had desired to be at Sandringham and when he arrived there his illness had been diagnosed as typhoid fever.

The Queen could not believe it. Bertie stricken with typhoid fever, the disease which had killed his father ten years ago and at precisely the same time!

It was like a horrible pattern – a judgement.

She felt that the train would never arrive; it was snowing; she sat brooding, thinking of that terrible time ten years ago.

Brown was beside her. ‘We’re there,’ he said gruffly. He fastened the cloak about her. ‘Can’t you stand still, woman?’ he demanded, and she smiled faintly; poor Brown, he was upset because he knew she was.

The carriage was waiting. Brown helped her in and off they went to Sandringham.

The place looked gloomy. She glanced up at it; she did not like it – fast clocks and fast parties. But he was ill now – her eldest son, sick as his father had been.

Lady Macclesfield, that good faithful woman on whom Alix relied, came forward to curtsey.

‘My dear,’ said the Queen, ‘what is the news?’

‘Very bad, I fear, Your Majesty.’

‘And the Princess?’

‘She is with the Prince.’

The Queen nodded.

‘It cannot be typhoid.’

‘I fear so, Your Majesty. And Blegge the groom who accompanied His Highness to Scarborough is suffering from the same disease. They must have caught it there.’

‘You had better take me straight to him.’

Lady Macclesfield inclined her head.

‘And the Princess, how is she taking it?’ asked the Queen.

‘The Princess is wonderful,’ said Lady Macclesfield fervently.

Alix had come to the door of the sickroom with Alice.

‘My dearest children,’ said the Queen with tears in her eyes, ‘what a blessing that you are together at this time.’

She kissed them both and they took her in to see Bertie. He looked unlike himself with the strange glazed look in his eyes and the unnatural flush on his cheeks.

Oh dear God, she thought, it is so like that other nightmare. And it is soon to be the 14th of December.

The very best doctors were attending him – not only the Queen’s favourite William Jenner but Dr William Gull, Dr Clayton and Dr Lowe. The whole country waited for news as the fever soared. Bertie’s failings were forgotten; he had become ‘Good Old Teddy’. He was a jolly good fellow; he liked women; he had a mistress or two, that only showed how human he was. He was a good sport; he was the sort of man they wanted to be King – and he was sick with the typhoid fever.

Forgotten were the grudges against the royal family. The Queen was with her son who was dying of the dreaded fever which had killed his father, and in the streets crowds waited eagerly for bulletins of his progress to be issued. The question on everyone’s lips was ‘How is he?’ He was better; then he was worse; there was some hope; there was no hope. Everything was forgotten but the dramatic illness of the Prince of Wales. The fact that the 14th of December was fast approaching seemed significant. It was more than that – it was uncanny.

During one of the more hopeful periods Alix went to St Mary Magdalene’s Church at Sandringham, having first sent a note to the vicar to tell him she would be there. She wanted him to pray for the Prince that she might join in but she would not be able to wait until the service was over for she must get back to his bedside.

The church was crowded and there was a hushed silence when the Princess, wan with sleepless nights and anxiety, appeared. All joined fervently in the prayers. But, commented the Press, Death played with the Prince of Wales like a panther with its victim. But while the Prince lived there was still hope. Alfred Austin, the poet, wrote the lines by which he was afterwards to be remembered:

‘

Flashed from his bed, the electric tidings came,

He is not better; he is much the same

.’

Alix, with Alice and the Queen, were constantly in the sickroom but Alix did not forget poor Blegge and made sure that he had every care and attention. Alice was a great help; quiet and efficient and having had some practice in nursing during the wars, she devoted herself to her brother and gave that little more than even a professional nurse could have given. Alix thought she would never forget what she owed her sister-in-law. The Queen, in times of real adversity, was always at her best. She would sit quietly behind a screen in Bertie’s bedroom, not attempting to interfere, only to be there in case she could be of use.

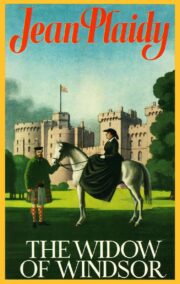

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.