A Negro woman who would not change her position. This is a novelty. We have not liked where we were, even when we didn't know what or how to change, when we simply dreamed of flying away, I'll fly away, I'll fly away, when I die. But I imagine flying away into his arms, dying to be reborn again, and dying again and again, waking after each little death into new pleasures. But it is not imagining; it is remembering from long ago with the faces changed. I am a maiden no longer. We arrived at his sister's house without speaking a word. But his eyes told me, his eyes told me, he saw me beautiful, and my whole self told him, I hear you, and I like so very much what I hear.

"he wasn't there. The whole family was out. He showed me to my room, and I took my hat from my head, pulling out the pin; then I loosed my hair from the tight ball that was making my head ache. I turned back toward the door; he was looking at me, a suitcase in each hand. His sister does not keep servants. I walked toward him but only in the sense that a piece of metal jumps toward a magnet. I was drawn. I was pulled. I took my suitcases with my own hands from his, turned my face toward his, opened my mouth wide. I waited for his lips. It was a wanton gesture. The first wanton gesture of my life. A gesture I had scorned when I had seen it in the whorehouse. He did not disappoint me. Lord, he did not disappoint me at all.

I have done what I would not have done had I contemplated it longer.

I'm terrified. Moving to being a woman of his, I have found myself in the neighborhood of Beauty's girls, the women with more than one man.

And then it is nothing at all like that or anything else I have known, this exquisite chaos.

This is what the psalmist was writing about in the Song of Songs. I recognize it at once. And I am afraid, not of his finding out, but of being this new person, a less than perfect person who has violated one of her most dearly held principles, and a person who has never felt such pleasure, a person I have never read about in books.

The pleasure of his body and the pleasure of his knowing me has carried me into some sacred territory I did not know existed. The mystery of making love to myself, for he is me, and I am he, and I know all that he and she want. In the church of this sex I am the preacher and the congregation. He is the preacher and I am the congregation. I am the preacher and he is the congregation. The call becomes the response and the response the call, and I am shouting and falling out. Eager to let the old Cinnamon die and let the new Cynara be born all the nights to come.

This is a sweet thing, sweeter than anything I have ever known. If there is anything better than being a free nigger on Saturday night, it's being a free Negro on Sunday morning; in his sister's bed I have my cake and eat it too.

We strolled out and about in the neigborhood later, easily arm and arm.

No one much knows me up here. Many bob their heads, as if to say what a handsome couple. This is a new experience for me, but it is a familiar one for him. I don't have to ask him to know that he has never in his life touched a white woman, would not dream of kissing one, and that if he did dream of it, it would be an act of defiance, not of desire. It is less comfort, much less comfort, to realize he has an eye for all the chocolate, and the caramel, and the coffee-colored beauties on these streets, sashaying out to enjoy their freedom. He likes to look at pretty women; he allows himself the luxury of resting his eyes on their faces. I let my elbow find its way into his ribs.

"God wouldn't a made women so beautiful if He didn't want men to take a moment to enjoy the beauty He created! Lord knows you women don't care enough about your own appearance to be peeking in any mirrors." I laugh at the silliness he wraps around some of his sharper truths. I am the only dark woman R. notices. I should find comfort in that fact but it-discomfits me.

Many folks recognize the Congressman, men in overalls, men in hats; he treats all alike and bows to them slightly. If there's a baby in arms, he threatens to kiss it, then shakes his head, walking forward and announcing, "Too much innocence for me to taint." R. is a rich man and perhaps a powerful one. My Congressman is a famous man and perhaps a powerful one. I'm beginning to discern the differences and how they might matter to me.

He asks me about my sister, Other. I have nothing more to say. I am bored with that story. Today is the day I go to see the doctor. There is no one else for him. The girl I saw dancing with him so long ago is an old friend of his family he might have married had he not met me.

Sdoctor, one of the first colored doctors in the country, had not very much to say-except he's seen my butterfly before and with it the aches in the bone-but there are other things I do not feel and that make him hopeful. He says the tired comes and goes. He says sometimes people die. He says I'm lucky I didn't have a baby, because sometimes that makes it worse.

Through this all he was more reserved than he had been before. Quite a bit more reserved. In fact, it took a few days for me to get the appointment. Finally, after the examination, when I was dressed and about to leave, he cleared his throat and said what I believe he had been trying to say all the while.

"Madam, when I first met you I was impressed by your deportment." (I would rather he had said intelligence and simple grace.) "You were in a difficult position, but you handled yourself with modesty. (I would rather he had modified the modesty perhaps by adding simplicity, humble modesty.) "All eyes could see that you were in the best and the worst sense of the word married. But you bore the yoke with..." (Did he call it grace?) "When you married, we were happy for you. Every Negro man who had a mother forced or cajoled by the master raised a cup to your victory. But now you come to town with no husband, only an intent on sullying the good name of one of the great dark men in the Capital City. I can't but join my fellow citizens in disapproving.”

“I don't think you know anything of my situation.”

“I can smell him on you." It was the most vulgar sentence I had ever had spat at me. I know what he meant. I had washed the linen at Beauty's. Being a doctor is another kind of washing of the bedsheets.

"He will never be elected again if he keeps up with you. Voting Negroes won't vote for a man living with another man's wife." I tried to interrupt him, but he wouldn't be stopped. "Whoever you think you are, in the polite society of Negro teachers and preachers and lawyers and doctors, you will always be the Confederate's concubine." He was on a roll. "You have a greater chance of being accepted among old white families than new colored ones." And he kept on going. "We're a prim and proper lot."

I hadn't thought of this. I hadn't thought of very much at all. My business in Washington is complete. I should return by the first train to Atlanta. It would be the sensible thing to do, and I am a sensible woman. No lady in any novel I know makes the kind of mistakes in books that I make in life. In all the literature I know, only one book comes close to what I feel. This is Great Expectations. Pip has a guilty family. Almost guiltier than mine. What is owed the rescuer? Do we always fall in love with those who rescue us? Didn't I know Miss Havisham in calico? What don't Estella and Other have in common? How easily Pip accepted his good fortune. I envy white boys that most of all-their certainty that they're going to be or get lucky. It occurs to them to live with great expectations. It occurs to them to do what they want and not worry about it. It occurs to R. to do that all the time. It doesn't occur to me at all. It occurs to me to run back to Atlanta.

R. has moved back into Other's house. Her children are there, and they need him. There's the grand staircase he once carried her up-and too many rooms to count.

This is where we huddled together when Precious died.

He sends a card 'round to my house, and I arrive at the appointed hour for my visit. We make love. He traces the butterfly on my cheek. And he asks if I am going to be all right. I tell him yes-and I tell him that I'm leaving him in the morning. In the morning, I'm leaving him.

I've just made up my mind to do it. When I said it, I was letting him know how unhappy I am. Now I'm hearing myself. I'm leaving in the morning.

"I gave you my name," R. says.

"I never told you mine," I reply.

Mammy never rode the train. I've got Lady's emerald ear bobs in my purse. I took them from Other's jewelry box. Some folks say emeralds are higher than peridots because there are more peridots in the world. It's what's scarce is high. Some folks say it's because emerald got a prettier color. I say it's because the rich folks found emeralds first and have more of them, so they say the peridot be just a little better than green-colored glass to give higher value to what they have a higher number of. Like white blood. But a man made the green-colored glass and God made the emerald and the peridot, and I can't help knowing the peridot is the pretty color of grass in the fall, the color of living things that survive the thirst of late summer when there's so much gold in the green. I see the peridot and the emerald are the same beautiful thing, and green glass is something altogether different.

I'm riding on the train up to Washington, alone. I don't send word ahead. No. All I have taken out of his house are her things. I take her things and leave her-him. This is the best I can do with this algebra of our existence. She gets him, and I get her things.

Everything he bought me I left behind, every pair of bloomers, every barrette, the peridot ear bobs the wedding ring, everything. I cannot go to my Congressman in R.’s things.

I went up to her room. I opened the closet: a sea of green, velvet, satin, silk; a gown or two in black; a blue day costume; hats. It was said around Atlanta that she liked green best because it is the color of money. But I who knew her from the first day either of us knew anything, knew that she loved green before she even knew what money was.

You don't see paper money on a cotton farm. You don't even see paper money on what it was and I have not wished to claim, a great Georgia plantation. On a place like that, in the place we lived together, half-sisters separated by a river of notions: notions of Negroes and notions of chilvary, notions of race and place, notions of custom and rage; in the country we inhabited in our childhood, you measured wealth in red earth and black men. There was nothing green in it.

Green were the leaves, green was the grass, green the grasshoppers, green all the insignificant pretty things, all the moving tokens of living, and that's why Other loved green, because she was, or saw herself to be, an insignificant pretty living thing. She didn't wear it because of the money or because it matched her eyes. She wasn't, in fact, vain. She knew I was the prettier one. Knew it right off and didn't let it worry her.

She wasn't pretty, but she had the capacity to distract men from noticing that. And now that my looks are vanishing with the years, I must borrow that from my sister; I must learn to make men not notice that I am not beautiful. Her dresses are a fine beginning. I will go to my Congressman in my sister's clothes.

I packed in her trunks. I look at my reflection in the window and it's a blurry thing, but I see me as I have never been before. I wear green well. For somehow, too, green is Daddy's Ireland.

Garlic told me the story. He got it from Mammy, who had got it from Planter. Planter ran out of Ireland with the law on his tail, wanted for a murder he had committed. And thieving he had thieved. He couldn't see other people have everything when his family had nothing.

And when things were too hot in that country, he quit it. That was her father and that was mine.

She was like him in that she killed. Miss Priss told me that story.

She, Other, and Mealy Mouth killed the Union soldier, robbed his dead body, and dragged him off in their chemises, all the while making light conversation with the family out the window. I come from a strong people. And I am like him in my willingness to leave my world to find a better one. It is a sister and a family I leave behind, not Other, not some thing.

Once in Georgia I had a sister who loved my mother dearly; she took care of Mama all her life, better care of her than I took. I hated her and buried her, and now I forgive her. Once in Georgia I had a mother I could not find my way to loving. I'm grateful that Other found a way and kept the path clean and brightly used. She made exquisite use of my mother's love.

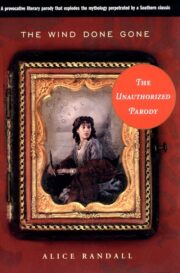

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.