And now it's my turn to make good use of her mother's love. Lady loved her black man in the bright light of day. If he will have me, I will love Adam, I will love my Congressman that way.

R. writes me letters it would bore me to return. He is someone else's dream. Whose dream I'm not sure. I suppose Beauty's. Beauty stretched the scope of her imagination to see him, to want him. She didn't like men, but she loved him. That's tribute. Other loved him when she had nothing else to love. It was a scrawny little pathetic love, and he wouldn't have it. And me, I loved him because he was the prize, and I wanted the prize to feel and know, taste and see that I could win it, but it was his power I craved, not him.

I tell him, I have been sleeping in my sister's bed. I don't want that anymore.

He tells me, I saw you before I ever saw her, wanted you before her.

But then you chose her because you could and she reminded you of me.

She was your daylight version of me. You betrayed me and I betrayed her on so many succulent occasions, too many succulent occasions. But I no longer have a taste for that meat. It's too rich for me. I want something simple, like a cold joint of ham, a slice of cornbread, and a big glass of buttermilk. I want to love a stranger who knows no one I know. You have been a father to me, and now that you look the part, I don't want you. His eyes well up. I won't give you a divorce. I'll live in sin. Proudly. You taught me that.

"What is your name," he asks me.

"Cynara," I say, walking out his door.

(am traveling unescorted. I feel nauseous. There are rascals of every hue on this train. Whatever remained of my good name will be gone by the time we reach Washington. Why doesn't anyone assume that a woman on her own wants to be?

The Congressman doesn't know I'm coming. The election is fast upon him; he doesn't need anything more to worry him. He can't imagine I will come.

R. imagined I would go. He sent a note 'round to my house. I call it my house because he gave it to me, because my name is on the deed, and because, as Beauty says and it's ugly to admit, I earned it.

R. wrote to say that if I was going to Washington, I could stay at "the house." He doesn't say my house, and he doesn't say ours. His kindness makes me cry. I am touched that he knew, could figure out, what I would do; his kindness makes me cry, but I can't accept it anymore.

Though I had money, they wouldn't rent a hotel room to an unaccompanied woman. I hired a driver to take me to my Congressman's sister's house.

When she opened the door she remembered me.

She is a ball tonight at the university. All the great Negro leaders of the city will be present. The election has come and gone. My Congressman will be Congressman no more when they swear in the new House. His sister has invited me to go with her party to the ball. I have things to tell him. I hope I can find the words.

We danced tonight. But before we danced I made preparations.

I had the slim gap-too the girl, Corinne, over for tea. suspected three or four things about her, one or two of them very important to me. Her flat chest and narrow hips reminded me of Mealy Mouth, only more. It was not easy issues I sidled up to, but I sidled up under the guise of sharing the story of a girl cousin who was married but rocked an empty cradle. She never swelled. The girl shrugged.

Her teeth were pretty, really, little pearls with a tiny little part in the middle of her smile. She was unashamed; things were as God intended them. If she was to live alone, well, she wasn't alone; she was with her parents. And she had the children in the settlement houses. There was important work to do and she was doing it. She knew how much the Negro population had increased since the end of the war.

How many more hungry stomachs and hungry minds. How little helpful political currency remained. "Odd," she said, making a delicate joke to change the subject, "my female trouble is that I have no female trouble." She took the bitter with the sweet and swallowed them both whole. "The only man who should marry me is a widower with five children who need someone to raise them. He would be lucky to get me.”

“What about the Congressman?”

“He wants a family. He kept talking to me about babies, and that's when I pulled away.”

“You love who you love," I say.

"You're blessed with whatever you're blessed with.”

“Wherever it comes from.”

“We're not in very different boats, are we?”

“You could not be more wrong," I say. Of a sudden I am frozen. After all these years she could not be more wrong.

If I find a way to offer my gift, will she find a way to accept?

pressed crushed flowers into the hem of my dress and into its creases. Scent rises in waves from my garment as I move. I tell him that he must marry the gap-too the girl. He laughs. We dance more. He pulls me deeper into the dance; we swirl, and I am drunk on the power that is flowing out of his body back into our country, our America. I look around me at these new Negroes, this talented tenth, this first harvest, the brightest minds, the sustained souls, the ones so beautiful they have received some advantage, and so strong they need not what they did not receive. Folks whose fathers were named Fearless and were freed because their master was afraid to own them. The ones who could intimidate from shackles. These beautiful ones. They are as close to gods as we have seen walk the earth. I dance and I see them dance in the darkening night as clouds roll in, covering the stars that shine upon the ones who survived the culling-out of the middle passage, and the mental shackles of slavery; the group that rose with the first imperfect freedoms to this city, to the Capital, this group of Negroes shining brightly as their-as our-flame burns down as our time passes.

This short night they call Reconstruction is ending. We dance in our twilight, and I know it. It is a secret greater than the secret I carry. Once in north Alabama rose a brilliant black man who no one gave a chance at all, rose and rode to Washington to take his place in the Capital City, a man who stole a woman from the oldest, richest family in the Confederacy. I saw that man. I saw him in the company of the nation's finest men, and I saw him stand toe to toe, and he was taller. But he is leaving the District of Columbia soon, and I don't know how long I will be around. I get too tired to remember. We swirl, the old fiddle sings us tunes, and when he pulls me closest, I tell him he must marry the girl and why. This is our Gotterdammerung.

This is the twilight and we are the gods.

Congressman married the doctor's daughter; that's what the town said.

The girl who attended New England Female Medical College. In a little African Methodist Episcopal church. I was the only witness.

I sold Lady's ear bobs and bought a little house out by the water in Maryland. Its weather-darkened bricks are from before the birth of our nation; the woods that surround my place are older still. The Frederick Douglasses are talking about buying some nearby property and building a home. When the time comes, I think I will be ready for neighbors. If and when the Douglasses come, they want to encourage others to migrate with them. It's starting to be hard times for Negroes in the city, and it's always been hard times for Negroes in the country. It's easier to live where fewer dreams are buried.

The son has been born to the Congressman, a legitimate heir. A beautiful, beautiful boy. He came into the world so pale, his mother fretted for days over his little Moses crib, praying for a little dark to come in. There were good signs from the start, a bit of brown ness 'round his cuticles and the tips of his ears, but like many lightskinned babies his eyes are a greeny-gray. I am to be the Godmother. They named him Cyrus after me. I took him back to an Episcopal church to be baptized; I couldn't wait for the Baptist immersion. If anything happens to my Godchild, I want him to go straight up to heaven and wait for his father and mother. I want no doubts at all.

Ah, my goodness. He is here. I call him Moses. I'm keeping Cyrus for his Poppa and Mama today. I tell him the story of Moses. I hold him above my head and I tell him about the mother making the cradle and setting it to float in the bulrushes. I tell him about the woman who put him in the cradle and the woman who found him. Some folks say she was the same woman, some folks say she was not. I know both women loved the baby. I am not so very well now. I think about the old days some now, and for the very first time I understand something about Mealy Mouth. The very best days are the days on which babies come. I'm so tired, I forgive her for what she had done to Miss Priss's brother, beat until he bled to death because something he said about a time he had had with Dreamy Gentleman. And I forgive Miss Priss for what she done to Mealy Mouth. And what that done to Other. And what that done to me. The very best days are the days the baby comes.

j is for you, my darling, emperor of the Congress of my heart. For you, Adam Conyers. Congressman Adam Conyers of Alabama, self-educated trained to the bar. I had intended to get a job on the new Negro newspaper. I had intended to write about the ladies and the parties they gave and the dresses they wore. I had intended to make you and him proud of me. All my life I saw the tangles that stood between me and love-until you. When I saw you, I refused to see the tangles, and I stubbed my toe, got swoll up and burst, and now it looks as if I'm going to ele.

I have never felt so loved as the day we waited for the baby's color to show or not show. And I knew because you told me, and I believed what you said, that you knew who the Mama was, and that was good enough for you. Anything of mine you loved. And lucky for me he's yours; it's been hard for me to love anything of mine. But just in time, loving what belongs to you means loving my own.

Tell your son all of this-when he's grown. Tell my Moses. Don't let it form him, and he will grow strong enough to master it. Shield the child from the truth of shackles, and no shackle will hold the man. The bars that cannot be broken are behind the eyes; the whippings you can't survive are the ones you give yourself. Let respectability be his first position; then nothing on this earth can shame him. Tell him his mother bought that respectability with lonely blood, and it is his birthright. Tell him that I was the chosen witness of the twilight, of you, my God. Ask him to pray against his mother's blasphemy. Tell him if we are as a people to rise again, it will be in him.

Tell him I only did one great thing: I bore a little black baby and I knew-what every mother should know and has been killed out of too many of my people, including my mother-I bore a little black baby and knew it was the best baby in the world. Tell your wife, tell my gap-too the Corinne, a lifetime of hating Other has made me fit for an eternity of loving her. Tell them both, I learned to share in peculiar circumstances. Now, the wind done gone, the wind done gone, the wind done gone and blown my bones away.

Cindy, nee Cynara, called Cinnamon, died many years later of a disease we now know to be lupus. She left her entire, not inconsiderable, estate to Garlic. She left her diary to Miss Priss, who left it to her eldest daughter, who left it to her only daughter, Prissy Cynara Brown.

The Congressman's son, Cyrus the first, never made it back to Congress, but his grandson, Cyrus the third, did. Today, Cyrus represents a district near Memphis, in Tennessee. He married a Nashville girl who practices law to support her horseback riding. They named their firstborn son Cyrus, Cyrus the fourth, but added Jeems in honor of one of her ancestors who had helped train the first American grand national champion. Little Jeems, as he is called, has his eyes on the White House.

Cotton Farm still stands just outside Atlanta. Jeems's christening, upholding long-standing tradition, occurred in its great hall, overlooked by an oil portrait of Garlic that Debt Chauffeur had painted just before he died. In his will, Debt left Cotton Farm, fallen on bad times and in disrepair, to Garlic, with the wish that he rot with the farm until he died and rot in hell after. Many thought R. just wanted some good company. Garlic used Cynara's money to repair the place.

When Garlic died, he left his pocket watch to the Congressman's son, along with half of Cotton Farm. The other half he left to Miss Priss, of course!

The mortgaged farm supplied the funds for Cyrus the third's successful election to Congress.

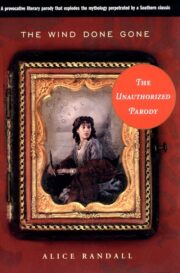

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.