Had it stopped? Could it stop? Had I ever really loved him, or had I just wanted what was hers? Was he mine before he was hers? Was it me he saw when he first saw her walking down the steps of Twelve Slaves Strong as Trees? We had been lovers for over a year then. When did I first hear that he had met her? I remember all the pages I had covered with my name changed to end with his. All the fake letters I signed Mrs. R.B., never thinking one day my name might change. Now, with a tear of a blue velvet riding habit, muddied, bloodied, never to be cleaned, all is possible. Was no more wanted than this extraordinary cake drawing ants?

wonder if Jeems can read. I've decided to write him a letter. It's going to say: Dear Jeems, Thank you for riding me to town. It's nice to remember old friends.

I was wondering how to close the letter when Jeems knocked right on the front door. I must have looked surprised. "This here's yo' front do', ain't it? This ain't Cap'n B. house, is it?”

“It's my house." I had never before had colored company of my own in the front room; now Jeems sat on my sofa visiting me. For a moment I stopped to wonder what Jeems would think, seeing me surrounded by such wealth. Then I remembered myself. We had exchanged our earliest confidences in silk-wallpapered hall sand richly furnished corners. We had both dusted and mopped and washed too many fine things, too much Limoge, too much Wedgwood, too many times, to retain awe. The former field slaves will have different relations to wealth (the wealth they see and the wealth they attain) than we, who, like Jeems and me, worked in the house. Familiarity, even with things, breeds contempt.

"Our Congressman from Alabama came for dinner the other night.”

“Sure like to meet him. Wonder if he knows Smalls.”

“Smalls? “

“The colored Congressman who seized Planter in '62. Sailed the ship right over to the Union Army.”

“How do you know that?”

“I was in the Confederate Army. I was all tore up when it happened." For a fleeting moment Jeems let his face-o-woe mask distort his features. But it just didn't fit anymore.

It popped off; he was laughing. "Cried crocodile tears.”

“I'm sure you did. And now?”

“And now I'm on my way to Tennessee.”

“Tennessee? “

“I'm no farmer.”

“They have something more than farms in Tennessee ? “

“Horses.”

“Ain't that Virginia, or Kentucky?”

“Tennessee. I've got some family living on a plantation just outside of Nashville. Belle Meade. They breed fine horses there. They could use a man like me." Pieces of our world were just spinning off. Ever since Emancipation.

Big and little pieces. Before we never went anywhere.

"Back when you were a young gal, you remember me from then?”

“I was never young.”

“Little, then.”

“Of course.”

“When I was little, I got whipped for you.”

“I don't remember that.”

“You didn't get whipped.”

“How I get you in trouble?”

“Trouble was there; you didn't get me in it. I let you ride my horse.

You were ten or eleven. I was thirteen or fourteen. Planter came down and saw you legs spread around that animal, saw it was my horse you was on, and whipped up some pain on me.”

“I remember riding. You never looked at me after that.”

“I'd like to take you riding again.”

“I'd like that too.”

“Would he mind it? Would it matter if he did?”

“No and yes.”

“No and yes?”

“He would mind ... if he bothered to notice.”

“But if a white man ...”

“Or some white man might mind for him. Someone who thinks Cap'n still owns you." And it be worse than a beating Jeems would catch. They're hanging black men all through the trees. Strange fruit grow in the Southern night. It's the boil on the body of Reconstruction, whites killing blacks. They didn't kill us as often, leastways not directly, when they owned us. All I will remember about Jeems is he caught a beating. There have been so many more pictures of Jeems in my head. Off to the side of those tall, red, laughing boys (who did the Grand Tour not of Europe but of the Southern universities), a lithe, taller man, observant, graceful Jeems. So many pictures, if in most, he, like me, was way off to the side in my mind's memory. But all those memory pictures started vanishing with a blow to my head, a blow of knowledge.

He'd caught a beating for me, and I had never even known.

He asked me how I was keeping. He told me he was sad for me about my Mama. His pity was too much. I told him not to be. I wanted to be asking him not to leave if he pitied me so much, but my old habit of not asking for what I won't get is strong. I was angry he was leaving, and jealous that he could imagine escaping the world we knew. I shook my head and told him the truth-because I thought it would hurt him. I told him I hadn't known my mother well and she didn't know me.

I had intended to silence him, but instead my candor loosened his mouth. He too had a tale to tell about mothers, much to my surprise.

"I never knew, I don't know who my Mama is. They bought me when I was a baby. Some idea Miz had to raise me with the Twins, so I could be their slave but not have 'niggerish' ways. Almost everything best about me is niggerish ways. But that's my defiance, and my defiance is pure Miz. I'm pure African and I got a mulatto mind. That's me.

Listen here, gal. Think on this. I 'member Miz always said to the boys she didn't want them marryin' Lady's daughters, not any of 'em.

She said, "You can't divide Lady from Mammy." Nobody knew what she mean, but I say, if it's true you can't divide Mammy from Lady, maybe you can't divide Lady from Mammy."

Now what that supposed to mean? I wanted to ride back with Jeems to Cotton Farm, to the answers those acres might provide, to a little more time with him. But he's only stopping back home before going on to Tennessee, straightaway. He's not stopping back through Atlanta, and I'm not returning home. I sent Garlic his cake in the mail.

Where did I think I was going? Who did I think I was going to? I got a letter from the plantation-that's what it is really, not a cotton farm-in response to mine. Can I even remember who wrote it? Does it matter? None of them really write, so somebody said it to somebody who wrote it down. Then they send it to me. They don't want me. I'm not welcome. They say, "She still here." Other, they mean. "Mammy gone.

Ain't no reason for you to " come There now.

I know that; I got to laugh. Yeah. Now. Whoa. Garlic. Garlic doing what Garlic do, protect the place. I see it. If Other find me there, Other may fall in hate with the place. She may realize 'bout R. and me. May remember something about Lady and me. My slave fear falls in beside me. That old fear that should be getting old, turning brown and be easy to blow into the wind, is ever green like the earth is ever red. Garlic's scared, I'm scared, that old fear that what we love might be sold: Mamas, Daddys, children ... the place ... a dress ... anything we love.

It's an old confusion, people turning into things. When folks is gone (sold, dead, run-off), you got a corn husk doll, a walnut-shell ring, fingertips of dirt on the hem of a dress. It happened so much, maybe now things turn into people. The house, Tata-Garlic could hear it speak. All it contained of the brown lives it had eaten; it was a living thing. Garlic walks into the great hall of the house like R. pushes in between my thighs; his eyes scream, "Sugar walls, sugar walls." Everything sweats in the heat. Garlic won't permit anything that might provoke Other to sell the place. Won't put Cotton Farm at risk at all. It's his sacred place.

I come to see what I ain't seen before. Me on the place might taint it. Soon she'll come back to 'lanta, and I'll see what Garlic say then. is involved in some kind of foreign currency exchange scheme. He came to know a good many foreign bankers during the war, when he was selling cotton on the foreign markets.

At home the pendulum seems to swing again, swinging away from the promise of real change: the change from little boys and little girls picking cotton to children reading and writing and wearing shoes and eating every day and one day getting to vote or getting to influence their father's or their brother's vote. It's like being pregnant. You are or you are not. A child has those things or does not. Conservative victories ended Congressional Reconstruction in Virginia before the state was admitted back into the Union-was it just last year? Was it 1870?

Reading or not, voting or not, these changes are small but necessary.

They are the salt on the meat of our existence, eating or not, sheltered or not, living or not. Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi-we're holding on to our votes there, even R.’s beloved South Carolina. When 1880 comes, I fear and he hopes, it will not look so very different for so very many from 1860.

But it will look different for me.

I want him to take me on a boat to Assisi or Florence, some place like that, some place I ain't seen, some place we could see together.

Dublin, maybe. Dublin's good. I used to hear Planter talk about there. Or Egypt. I like it when he tells me Egyptian stories and calls me Cleopatra, except the snake bit her. Some folks say my house is a cross between Egyptian Revival and Charleston architecture. Some folks say my columns look like bundles of broomsticks. R. says they look just like bundles of papyrus reeds. I know I own three of Mr. Shakespeare's plays, Romeo and Juliet, Cleopatra, and Othello. Nurse reminded me of Mama. She didn't know who Juliet was and couldn't do nothing to protect her, really.

I asked him this morning at breakfast; he says I must wait.

I'm tired of reading and writing and cooking two meals when I don't have Cook in. I have a little business. From the money R. gives me, sometimes I make little loans to the freemen. They pay me back. I made a loan today. Other has a business. Beauty has a business. Other got men working for her; Beauty's got gals. Me, I got R., but R.’s done working. Now, he invests and sometimes it looks like he's chasing respectability the way he used to chase money, and sometimes it looks like he's chasing power.

Some of the freemen I loan money to come from Cotton Farm. Everybody say Other feeling Mammy's death hard. She doing poorly. Her beauty just about drained from her. I think that's the reason she doesn't come back to town. I look in the mirror and wonder if the same thing has happened to me and I stay blind to it. It is one of the good things about being colored-we don't show our age until all at once, all of a sudden, we need to. Then we get fat and old quick, quick enough to keep away those we need to keep away. I've heard R. talk about it. The orthodox ladies shave their heads and the yellow nigger girls get fat. Either way, only their own man wants them.

R. loves the old ways of Savannah and Charleston and Njawlins; only these cities are old enough for him now. I used to be his exotic adventure, and now it is I who is old and familiar. Other is just a reminder of the dearly departed. He takes me in his arms like a child now, and I know he can see his little girl's smile on my face. Planter's smile. I wonder if that is why he turns away from me.

R. brought me a ring back from Charleston. As if we could marry before they divorce. As if everyone will forget he was a war profiteer before he was a blockade buster; as if I can forget he was a Confederate soldier.

The ring sits on my finger gold and green. And I can't help liking it, because it looks like something Other would have liked. If I die and he gave the ring to her, she would wear this emerald never even knowing it had been on my finger. Some things are so pretty, you wear them even when you know where they've been. Most times, most folks, you just don't know.

I say the ring is perfect. The stone is perfect. R. says when you looking to see if you got a real jewel, you look for the flaws. I don't know what he's talking about. Sometimes he just talks.

I wonder where we would be married. In my little gray African Methodist Episcopal church, Bethel, or in his big white plain Episcopal one?

L. P. Grant gave the land for the "African church" before I was born.

After the war he claimed he "never gave the lot for free negroes to worship on, but for slaves." He wanted his land back. In the end, Bethel got Grant's land and Grant's anger. He loved the little black congregation enough to give it the land, but he hated when it asserted its independence from the white Southern Methodist Church. But then again, it was prominent white citizens who pressed Grant to let Bethel keep his land.

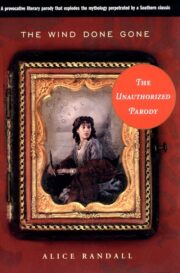

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.