'Here,' she said, coming back into the gallery.

Hugo took the glass from her without looking up and gave Catherine sip after sip, watching her face and talking to her in a low, gentle voice. When she stopped sobbing, sat up, and wiped her face with her handkerchief, he looked around at Eliza and said, 'Here! Make her ladyship's bed ready! She should sleep now.'

Eliza ducked a curtsey and went through to Catherine's room.

'Have you anything to help her sleep?' he asked Alys over his shoulder.

She went back to the room she had shared with Morach. A log had shifted on the little fire and the shadows leaped and danced around the bed. For a moment it looked as if there were someone sitting on the chest at the head of the bed with their face turned towards the door. Alys leaned back against the door and pressed her hand hard against her heart. Then she fetched the drops of crushed poppy seeds for Lady Catherine, so that her ladyship might sleep well in the comfort of her great bed.

Hugo took the draught without thanks and led Catherine – one arm around her thick waist – out of the gallery and into her bedroom.

Alys watched them go, saw Catherine's head droop to Hugo's shoulder, heard her plaintive voice and his gentle reassurances. Alys tightened her lips, curbing her irritation.

'Won't you be afraid to sleep tonight on your own?' Eliza asked Alys as the door shut behind the couple. 'No,' Alys said.

Eliza gave a little scream. 'In a dead woman's bed!' she exclaimed. 'With the pillow still dented with her head! After she had drowned that very day! I'd be afraid she would come to say her farewells! That's what they do! She'll come to say her farewells before she rests in peace, poor old woman.' Alys shrugged her shoulders. 'She was a poor old woman and now she's dead,' she said. 'Why should she not rest in peace?'

Ruth looked sharply up at her. 'Because she is in the water,' she said. 'How will she rise up on the Day of Judgement if her body is all blanched and drenched?'

Alys felt her face quiver with horror. 'This is nonsense,' she said. 'I'll not hear it. I'm going to bed.'

'To sleep?' Mistress Allingham asked, surprised.

'Certainly to sleep,' Alys replied. 'Why should I not sleep? I am going to get into my nightshift, tie the strings of my cap and sleep all the long night.'

She stalked from the room and shut the door behind her. She undressed – as she had said she would – and tied the strings of her nightcap. But then she pulled up her stool to the fireside and threw another log on the fire, lit another candle so that all the shadows in the room were banished and it was as bright as day, and waited and waked all night – so that Morach should not come to her, all cold and wet. So that Morach should not come to her and lay one icy hand on her shoulder and say once more: 'Not long now, Alys.'

The next day Alys summoned a maid from the kitchen and they cleared the room of every trace of Morach. The kitchen maid was willing – expecting gifts of clothes or linen. To her horror at the waste of it all, Alys piled it all up and carried it down to the kitchen fire.

'You're never burning a wool gown!' The cook bustled forward, eyeing the little pile of clothes. 'And a piece of good linen!'

'They are lousy,' Alys said blankly. 'D'you want a gown with a dead woman's fleas? D'you want her lice?'

'Could be washed,' the cook said, standing between the fire and Alys.

Alys' blue eyes were veiled. 'She went among the sick,' she said. 'D'you think you can wash out the plague? D'you want to try it?'

'Oh, burn it! Burn it!' the cook said with sudden impatience. 'But you must cleanse my hearth. I cook the lord's own dinners here, remember.' 'I have some herbs,' Alys said. 'Step back.' The cook retreated rapidly to the fire on the other side of the kitchen where the kitchen lad was turning the spit, leaving Alys watched, but alone. Alys thrust the little bundle into the red heart of the fire.

It smouldered sulkily for a moment. Alys watched until the hem of Morach's old gown caught, flickered and then burst into flame. Alys pulled a little bottle from her pocket. 'Myrrh,' she said and dripped one drop on each corner of the hearthstone, and then three drops into the heart of the fire. 'Rest in peace, Morach,' she said in a whisper too low for anyone to hear. 'You know and I know what a score we have to settle between us. You know and I know when we will meet again, and where. But leave me with my path until that day. You had your life and you made your choices. Leave me free to make mine, Morach!'

She stepped back one pace and watched the flames. They flickered blue and green as the oil burned. On the other side of the kitchen the cook drew in a sharp breath and clenched her fist in the sign against witchcraft. Alys paid her no heed.

'You cared for me like a mother,' she said to the fire. The flames licked hungrily around the cloth and the bundle fell apart and blazed up, shrivelling into dark embers. 'I own that now. Now it is too late to thank you or to show you any kindliness in return,' Alys said. 'You cared for me like a mother and I betrayed you like an enemy. I summon your love for me now, your mother-love. You told me I did not have long. Give me that little space freely. Leave me to my life. Morach. Don't haunt me.'

For a moment she paused, her head on one side as if she were listening for a reply. The dark smoky smell of the myrrh filled the kitchen. The kitchen lad kept his face away from her and turned the spit at extra speed, its squeak rising to a squeal. Alys waited. Nothing happened. Morach had gone.

Alys turned from the fire with a clear smile, nodded at the cook. 'All done, clothes burned and the hearth cleaned,' she said pleasantly. 'What are you making for the lord's dinner?'

The cook showed her the dozen roasted chickens waiting to be pounded into paste, the almonds, rice and honey ready for mixing, the sandalwood to make the mixture pink. 'Blanche mange for the main course,' she said. 'And Allowes – I have some good slices of mutton. And Bucknade. Some roasted venison. I have some fish, some halibut from the coast. Would you want me to make something special for Lady Catherine?' she asked ingratiatingly.

Alys considered. 'Some rich sweet puddings,' she said. 'Her ladyship loves sweet things and she needs all her strength. Some custards, perhaps some leche lombarde with plenty of syrup.'

'She's growing very fat and bonny,' the cook said admiringly.

'Yes,' Alys said sweetly. 'She is fatter every day. There will scarce be room for my Lord Hugo in her bed if she grows much bigger. Send a glass of negus and some custards and some cakes up to her chamber, she is hungry now she is in her fifth month.' The cook nodded. 'Yes, Alys,' she said. Alys paused on her way to the door, one eyebrow raised.

The cook hesitated, Alys did not move. There was a powerful silence as the cook met Alys' blue eyes and then glanced away. 'Yes, Mistress Alys,' she said, unwillingly giving Alys a title. Alys looked slowly around the kitchen as if defying anyone to challenge her. No one spoke. She nodded to the kitchen boy and he scrambled from the spit to open the door for her into the hall. She passed through without a word of thanks.

She paused as the door closed behind her and listened in case the cook should cry out against her, complain of her ambition, or swear that she was a witch. She heard a hard slap and the spit-lad yell at undeserved punishment. 'Get on with it,' the cook said angrily. 'We don't have all day.'

Alys smiled and went across the hall and up the stairs to the ladies' gallery.

Catherine was resting in her room before dinner, the women gathered around the fireside in the gallery were stealing an hour of idleness. Ruth was reading a pamphlet on the meaning of the Mass, Eliza was daydreaming, gazing at the fire. Mistress Allingham was dozing, her head-dress askew. Alys nodded impartially at them all and walked past them to her own chamber.

The maid had swept up the rushes from the floor as she had been ordered, and left the broom. Alys took it up and meticulously swept every corner of the room, sweeping the dust and the scraps of straw into the centre of the room. Carefully she collected it all and flung it on the fire. Then she took a scrap of cloth and wiped all around the room, everywhere that Morach's hand might have rested or her head brushed. Every place where her skirt might have touched or her feet walked. Round and around the room Alys went like a little spider spinning a web. Round and around until there was no place in the room which she had not wiped. Then she folded the cloth over and over, as if to capture the smell of Morach inside the linen – and flung it into the heart of the fire.

The maid, complaining, had brought new rugs and a spread for the bed and Alys smoothed them down over the one solitary pillow. She shook out the curtains of the bed and tied them back in great swags. Then she stepped back and looked around the room with a little smile.

As a room for two healers, two midwives for the birth of the only son and heir, it had been generous. It was as big as the room next door where the four women slept, two to a pallet-bed. As a room for one woman, sleeping alone, it was noble. It was nearly as big as Lady Catherine's, the bed was as large, the hangings nearly as fine. It was colder than Catherine's room – facing west out over the river – but airier. Alys had chosen not to scatter new herbs and bedstraw on the floor, but the room smelled clean. It was clear and empty of the clutter of women, no pots of face paint, no creams, no half-eaten sweetmeats like in Catherine's room. Alys' gowns, capes, hoods and linen were in one chest, all her herbs, her pestle and mortar, her crystal and her goods were in the other.

There was one chair, with a back but no arms, and one stool. Alys drew the chair up to the fire, rested her feet on the stool, and looked into the flames.

The door opened. Eliza Herring peeped into the room. 'There you are!' she said awkwardly.

Alys raised her head and looked at Eliza, but said nothing.

Eliza looked around. 'You've swept it,' she said, surprised. Alys nodded.

'Aren't you coming out to sit with us?' Eliza asked. 'You must be bored in here on your own.' 'I'm not bored,' Alys said coolly. Eliza fidgeted slightly, came a little further into the room and then stepped back again. 'I'll come and sleep in here with you, if you like,' she offered. 'You won't want to be on your own. We could have some laughs, at night. Margery won't mind me moving out.' 'No,' Alys said gently.

'She really won't,' Eliza said. 'I already asked her, because I guessed you would want company.'

Alys shook her head. Eliza hesitated. 'It's bad to grieve too much,' she said kindly. 'Morach was a foul old woman but she loved you – anyone could see that. You shouldn't grieve for her too long, Alys. You shouldn't sit here all alone, grieving for her.'

'I'm not grieving,' Alys said. 'I feel nothing. Nothing for her, nothing for you women, nothing for Catherine. Don't waste your worry on me, Eliza. I feel nothing.'

Eliza blinked. 'You're shocked,' she said, trying to excuse Alys' coldness. 'You need company.'

'I don't want company and I cannot have you sleeping in here,' Alys said. 'Hugo will want to be on his own in here with me very often. I have prepared the room for the two of us.'

Eliza's eyes widened, her mouth made a soundless 'O'. 'What about my lady?' she demanded when she could find her voice. 'She may not be well, Alys, but she has enough life in her to throw you back into the street. Hugo would never cross her while she is carrying his child.'

Alys' lips smiled without warmth. 'She will become accustomed,' she said. 'Everything is going to be different now.'

Eliza blinked. 'Just because Morach drowned?' she asked.

Alys shook her head. 'It is nothing to do with Morach. I am expecting Hugo's child. It will be a son. Do you tell me that he will let Catherine rule me, when she is carrying one son and I another?'

Eliza gasped. 'But hers is legitimate!' she protested. Alys shrugged. 'What of that? You can never have too many sons and Hugo has no other. I think they will treat them both as heirs until they know that the succession is safe, don't you?'

Eliza held the door against her and peered around it. 'Is this dukering?' she asked. 'Divining and dukering?'

Alys laughed confidently. 'This is mortal woman's knowledge,' she said. 'Hugo has been lying with me ever since he came back from Newcastle. Now I am with his child I want a room to myself and perhaps a little maid to wait on me. Why should Catherine object? It will make no difference to her.'

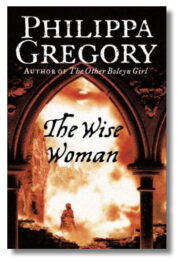

"The Wise Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wise Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wise Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.