Yet the first thing that had happened when they entered the house was indicative of what was to happen for the coming days. In the large hallway of Hetherington Manor, displayed on the wall facing the main door was a painting by Joseph Turner. It was Robert's pride and joy, a picture of sunset on a turbulent ocean. Most visitors commented on it. There was nothing unusual, then, in Helen's stopping to do so. But the intensity of her reaction was unusual.

She had dropped the one hatbox that she carried, just inside the door, without even noticing that a footman stood with hand outstretched to take it. She had not stopped to remove her heavy cloak and bonnet as Elizabeth had done. She had walked forward, almost like a sleepwalker, her lips parted.

"Oh!" was all she had said at first.

Elizabeth had smiled and joined the girl after handing her things to the footman. The nurse, who had been traveling in the baggage coach behind them, had already taken the baby upstairs to the warmth of the nursery.

"Do you like it?" she had asked.

Helen had not immediately replied. "Who did it?" she had asked at last without withdrawing her eyes from the painting.

"Mr. Turner," Elizabeth had said. "Have you seen any of his other paintings?"

"Oh, no," Helen had replied. "There are more? How I envy him!"

Elizabeth had laughed. "Do you paint?" she asked.

"I thought I did," Helen had said, "but I see now that I only dabble. Oh, I have tried and tried to be like this. But everything is of the surface. I cannot get beneath the surface to the real life. This man has done so. Look! He has become part of that sunset. He has been into it and into that ocean. He has painted it from the inside out. Oh, how envious I am."

Elizabeth had looked at the girl, startled. "You take painting seriously, I see," she had said.

"Oh, I did," the girl had replied. "But I can never be this good. What a failure I am."

"And what a foolish thing to say," said Elizabeth. "If you love painting, Helen, and if you have an earnest desire to reach perfection, then you are a failure only if you give up. That would mean that you do not have the courage to try."

Helen had seemed to be aware of her presence for the first time. She had given her hostess a look of bright interest. "Of course you are right," she had said. "Self-pity has become such a habit with me lately that I am afraid I have become overindulgent. You do understand too, do you not? My family has always ridiculed my paintings. Papa says they look more as if I had attacked the paper than painted on it." She had laughed suddenly. "Perhaps you will agree with them if you ever see any of my work."

"We shall have to put it to the test," Elizabeth had said. "And it is fine for you to be standing here talking, Helen. You are still wearing your cloak. I am feeling decidedly chilly. Let us go up to the drawing room. I have been told that tea and scones await us there."

On the following day, when Elizabeth was in the sitting room writing a lengthy letter to Robert, Helen had come into the room carrying a roll of paper. Elizabeth had smiled at her.

"I thought you might like to see one of my drawings," she had said. "I did not bring any of my paintings. This one is not good. It is the only portrait I have ever attempted. And it does not really look like him. But I like the picture anyway." She had unrolled the picture almost apologetically and turned it for Elizabeth to see.

Elizabeth had been almost speechless, as she wrote to Robert afterward. "Oh, Helen," she had said, "how did you know? How could you know him so well? Yes, that is William; that is his very essence. I don't think I even knew it myself until this moment."

Helen had looked doubtful. "But do you not think," she had said, "that I should have sketched him with a serious expression? He is far more often serious than smiling."

"Oh, yes," said Elizabeth, "but this is the real William. All his inner kindness and gentleness show through here. This is as he should look always, Helen. And this is how he was when you knew him?"

"Yes," Helen had said, "but it is not a good portrait, after all. I was deceived. I loved him, you see."

"And love him still," Elizabeth had stated gently. "It will not do to deny the truth, you know, Helen. Do you carry this picture around with you only because it is a good work of art? I do not know the truth of last summer, but I do know William Mainwaring. For all the evidence to the contrary, I cannot believe him to be the heartless villain you consider him to be. Don't suppress your bitterness. Face it and think about it. Perhaps you will find a different answer than the one you have accepted so far."

Helen had rolled the portrait in her hands. She had looked sullen again. "I want to forget," she had said. "I want to think only of my child and how I can best prepare to give him a good life."

"I am sorry!" Elizabeth had leaned forward and placed a hand over one of Helen's. "I do not mean to preach at you or be forever handing out unsolicited advice. I shall never refer to the matter again, Helen. Let us be friends and try to make each other happy here, shall we? I must finish writing to Robert and then I must visit John for a while-I have seen him only briefly this morning. After that, shall we go for a walk? It looks overcast and cold out there, but the fresh air will do us good. And the land around here is very picturesque. Perhaps you will get some ideas for painting again. If it is true that you have done none since leaving Yorkshire, I suspect that it is high time you got back to it."

And that is exactly what had happened, Elizabeth reflected rather ruefully a few days later. Helen had not actually done any painting yet, but she had made copious preparations. She had been hardly indoors, but had trudged around the grounds, sketchpad in hand, staring and touching, trying to get behind the outer surfaces to the reality within, she told a fascinated Elizabeth. The latter felt very much alone without her husband and without any companionship except that of her baby and the occasional meeting with her guest.

But she was pleased, nevertheless. Helen was clearly not the insipid, moody little girl that she had expected. In fact, Elizabeth suspected that she was a highly intelligent and artistic girl, whose talents had never been either appreciated or encouraged. And the change of scene was obviously doing her a great deal of good. There was a new sparkle in her eyes, fresh color in her cheeks, and a welcome intensity in her expression. Elizabeth was beginning to like her and she was beginning to understand why William had fallen in love with her. She even felt she had a glimmering of understanding of how those two had come to flout convention to such a shocking degree as to have created a child outside marriage.

She longed for the arrival of Robert at the end of the first week. She wanted to share her discoveries with him, and she wanted to discuss with him how they might best bring together again these two people who so clearly loved and needed each other.

Helen had indeed become absorbed again in her painting, but not quite to the extent that Elizabeth believed. She was enchanted by the scenery of the Hetherington grounds. There were no formal gardens, and Helen was glad. She could admire formality, but she could not love it. It seemed almost sacrilegious to take nature and try to subdue it to man's idea of beauty and symmetry. Nature was perfect in itself. Man could not improve on it. There seemed to her almost an absurdity about constructing little hedgerows, all carefully cut and shaped so that they lacked any spontaneity, and flower gardens, where flowers were given strict instructions to grow a uniform color and a uniform height. And marble statues of Greek gods or cherubs always seemed to her totally inappropriate in an English countryside. The rains and the temperate climate of England produced vegetation enough and color enough that it did not need embellishment. It was not that the Hetherington grounds were uncared for. She had discovered that the gardener had four helpers and that all five of them were constantly busy. But their efforts were used to aid nature rather than to distort it.

At this time of the year most people would have found the gardens drab. Most of the trees were already bare. There were no flowers remaining. Only greens and browns, Helen noted with satisfaction. The shadings of those two colors were almost infinite. One could spend days noticing the contrasts, undistracted by the gaudier colors of summer. She wandered, drinking in the late-autumn beauty of it all, forgetting for long stretches of time the cold, her obligations to her hostess, her pregnancy, and the uncertainty of her future. Soon she would beg paper and paints from Elizabeth and try to paint some of her feelings out of herself. She was almost ready.

But she was not always absorbed by such thoughts. Just as frequently, as she wandered over the lawns and among the trees, her eyes alone saw them. Her mind was wholly taken by the picture of a different landscape, of tall old trees and wild, untended undergrowth, of a dilapidated hut and a meandering stream. And of herself there, caught up in a dream world, unaware of the realities of life

As she leaned against an oak tree in the Hetherington grounds, her hands tracing the contours of its trunk, in her mind she felt the old oak tree by the stream, its bark older and rougher. And she felt William's hands above hers, William behind her. And in her imagination she turned to him as she had turned in reality several months before. She relived his kiss, his lovemaking. She relived each of their three meetings, remembering every look, word, and touch that had passed between them.

For the first days she refused to recall what had followed. She had resolved when she came here to put the pain behind her. For the sake of her unborn child she needed to achieve some sort of tranquility, and brooding on the wrongs that she had done and those that had been done her was not a way to achieve that aim. She concentrated wholly on those three afternoons, when she had fallen in love and when she had given her love freely without a thought of the consequences.

On one of those afternoons her child had been conceived. And for the first time Helen was fiercely glad that it had happened. Even if she had the choice now, she would not have things differently, she believed. For the rest of her life she would have her son or her daughter to remind her that at one time she had found her ideal. She had always wanted perfection in her life. Well, she had it once-a perfect love. She could never love William again as she had then, and she could certainly never trust him again, but once, for the space of a few days, she had loved. And she was glad that there would be a permanent and perfect memento of those days. What could be more perfect than a child? A child who would be part of him, who perhaps would look like him?

The shining eyes and the glowing cheeks that so pleased Elizabeth were due as much to this acceptance of the past as they were to the renewal of her determination to paint.

Although Helen sometimes forgot that she was a guest and that she should spend more time with her hostess, she did enjoy Elizabeth's company when they were together. She had been grateful to her for the invitation to Hetherington, but she had not really expected to like her hostess. Despite what Elizabeth had said to her about her own sufferings, Helen had labeled her as one of the privileged in this life, as one who had not really been made to face the harshness of life as most other people had.

She was pleasantly surprised, therefore, to find that Elizabeth had a warm personality and a keen intelligence. Her love for her husband and son were no affectation. She wrote to the marquess daily, though he was planning to come a week after their own arrival. She spent a large portion of each day with her son instead of abandoning his upbringing to the nurse. And her love was not confined to her own family. She told Helen about her brother John and his wife, Louise; and the affection she felt for them and their growing family-two children, soon to be three-was very obvious.

She talked sometimes with enthusiasm and amusement about her come-out Season in London, when she had met the marquess and when his eccentric grandmother had aided and abetted their growing love and their eventual elopement. And she spoke of the people of the village of Granby where she had lived for the six years of her separation from her husband, as a governess and companion. There was no bitterness in any of these stories, but there was a great deal of affection for the people she had known. And, of course, Helen could never forget that the marchioness had saved her from a nightmare situation.

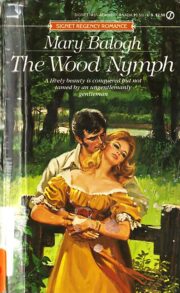

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.