He smiled at her and drew his thumb lightly over her lips before straightening up again and turning to stride away through the trees and quickly out of her sight.

Helen did not immediately leave. She noticed, in something of a daze, that one of her feet was still dangling in the water. She pulled it out and tucked both feet under the hem of her dress, not bothering to dry the wet one first. What a coil she was in! In the past half-hour she had broken just about every rule that should guide her actions as a lady. The first meeting with Mr. Mainwaring could be discounted. She had not expected him then. She could not be expected to feel any guilt about talking to him on that occasion. Mere civility had demanded it, even if not the deception. But this time!

She admitted to herself quite freely that the hope of a meeting with him was what had really brought her there. And she had deliberately invited closeness. She could have stayed in the tree and talked to him from that safe distance. But no. She had descended as fast as her legs would carry her as soon as he had suggested it, and she had invited him to come and sit with her on the bank. She had used feminine wiles that she had not known she possessed. It was most improper to sit on the bank of a stream in the midst of a dense wood with a gentleman, unchaperoned.

And that was not all. She had felt the spark of something between them when he had said that he might learn her passion for nature. She had known he was going to kiss her for a full second before she had felt his mouth on hers. And she had done nothing to avert the peril as she could quite easily have done by laughing or breaking eye contact with him or doing any of a hundred and one little things that would have broken the tension of the moment. If she were a lady, she would have done one of those things. And she would have been walking away from there just as fast as her legs would carry her.

Truth was, she had wanted him to kiss her. What a shocking admission! They had not even been formally introduced. And even if she could be excused for that first kiss, about which she had had only a second's warning, there was no excuse at all for the kiss that followed. She even had the uncomfortable feeling that she had invited it. The first one had not been enough, a mere brushing of lips. But the second! She did not know by what instinct she had parted her lips, but she could feel now the intimacy of his open mouth against hers and of his tongue touching her own. She could feel her breasts pressed against the hardness of his chest.

And she had reveled in the feelings. She should have been deeply shocked. She should, in fact, have swooned quite away at having done something she should not even have dreamed of doing outside the marriage bed. But the only fact that made Helen feel guilty was that she did not feel ashamed. The day was brighter for the embrace. She was the happier for it. She lifted her head and gazed at the sky, where the same powerful gale was blowing wisps of white across its surface. She wished she were up there so that she could feel the wind in her hair and on her hot cheeks.

She wondered if she was falling in love. Helen believed very strongly in love. She had always thought it must be the most glorious and sublime feeling of which one could be capable. But she had never expected it to be part of her experience. She had never felt even a mild liking for any of the men she had met since she left the schoolroom. But this could not be love. It had come too suddenly. She hardly knew the man. He I probably be quite different if he knew her real identity. He would then surely be as prosy and as starchy as all the other gentlemen of her acquaintance.

Helen's face suddenly felt hotter than ever. Of course, soon he was bound to find out. There was no way she could escape indefinitely meeting him in public. There was a ball at Lord Graham's house the very next night, and she was bound to meet him there. The ball was being given largely in honor of his arrival in the neighborhood. How would she be able to face him? What would his reaction be when he knew that the girl he had teased and kissed in the woods was really Lady Helen Wade? He would probably feel obliged to do something stupid like offer for her. And how mortifying it would be to receive an offer of marriage for such a reason. Especially when one was beginning to imagine oneself in love with the man.

Helen frowned and rested her chin on her raised knees. Was Mr. Mainwaring a rake? she wondered. Was he out to take her virtue just because he believed her a village wench, someone who did not count? She would hate to think so. Undoubtedly, though, he would not have behaved so had he known that she was a lady. But then, she had behaved so, had she not, knowing that she was a lady? The problem was just too complicated. Anyway, if the man were a rake, he would not have been contented with the kiss they had shared. And he was the one who had ended it. Helen did not like to examine the question of when she would have put an end to the encounter.

Of one thing she was sure. She wanted to see him again before the inevitable exposure of her identity the following evening. She should not, of course. She should not play with fire. But he was going to read her the poems of Mr. Wordsworth. She smiled guiltily and glanced in the direction of the hut. She could have produced her own copy of Lyrical Ballads and read to him. Would he not have been surprisedl

Looking at the hut made her consider another problem. What if she returned tomorrow to find that he was already here? Either he would see her in her everyday clothes and know the truth, or she would have to steal away and miss the chance of a meeting with him. There was only one solution. She would have to take the dress with her and hide it somewhere else so that she would be wearing it already when she arrived.

Ten minutes later Lady Helen Wade emerged from the hut wearing the same riding outfit as she had worn on the previous occasion. She carried the faded cotton dress over her arm. She gazed lingeringly in the direction of the riverbank before walking away toward the western edge of the wood, where she had tethered her horse.

Chapter 4

“Mr.Mainwaring has asked me for the first set this evening," Melissa announced with studied casualness at the breakfast table the next morning.

"I think it only right and proper that he should," her mother replied. "He has singled you out quite markedly, my love, and I think everyone would expect that be will show you deference tonight."

"He has also suggested that we ride together one morning," Melissa continued, "but I told him that I would have to consult Papa."

"Young puppy would probably fall off at the first fence," the earl grumbled into his beefsteak. "Or else he would ride an extra two miles to avoid the fence. Ride with him, Melly, if you must. You will be as safe with him as with a nursemaid."

'"It would not surprise me in the least if he were to declare himself before the week is out," the countess said. "It would be a splendid match for you, my love, for all that he is only a mister. He must be worth twenty thousand a year if he's worth a penny."

“More, I shouldn't wonder," said the earl. "The fella owns half of England and Scotland."

"I think you exaggerate somewhat, my love," his wife suggested. "But really, Melissa, it would be a grcat triumph to have a daughter married to a man of such consequence. Now, if only we could find someone equally distinguished for dear Emily."

“I am not at all in a hurry to fix my choice, Mama," that young lady was hasty to add. "I have not yet met the man I consider worthy of my esteem. I would think it somewhat vulgar to snatch the first presentable man to appear in the district since we emerged from the schoolroom."

"Quite right too, my love," her mother agreed, not appearing to notice the slur that had been cast on her younger daughter. "And then, of course, there is Helen. I really do not know what we are to do with her." She gazed hopelessly and fondly at her youngest, who had sat silently through the preceding conversation.

"You need not worry about me, Mama," she said now. "I shall stay a spinster and remain with you and Papa."

"Yes, but you see, child," her mother said quite seriously, "you will never be a comfort to my old age if you continue to play the pianoforte as if it were your mortal enemy and work your embroidery as if it called for your undivided attention and wander, off whenever your presence is most called for."

Helen lowered her eyes and crossed to the sideboard for more coffee.

It was going to be the most awful day in her life, Helen reflected somewhat later as she wandered to the stables to watch the grooms brush down the horses and clean their stalls. This evening she was going to have to bear the introduction to Mr. Mainwaring. That was bad enough. But through a restless night she had reconciled herself to its inevitability. If she could only meet him once more during the afternoon, before he knew the truth, she would be satisfied. If only he would kiss her again… But she did not dwell on the thought. Just to see him and talk to him would be enough, and to hear him, perhaps, read to her some of Mr. Wordsworth's poetry.

But now to have found out that he had promised. Melly the first dance and had already asked her if she would ride with him one morning! And he had taken her driving the Sunday before. Was he developing a tendre for Melly? Was Mama right, and they might expect a betrothal between Mr. Mainwaring and her sister in the near future? Somehow the thought made her feel slightly sick. She wandered over to her own horse, which had been led out of its stall. She patted its nose and buried her face briefly against its mane.

Of course, it was all very possible. He knew her only as a rather ragged girl. He had talked with her twice, kissed her once. It was ridiculous to dream that perhaps his thoughts were centered as much on her as hers were on him. If he did think of her, it was probably with some amusement and perhaps with some interest in carrying on a mild flirtation. A man of his class just did not lose his heart to a lower-class girl. And a man of his class would see no dishonor in flirting with a servant girl, or even in having an affair with her, while conducting a serious courtship of a lady who was his social equal. There was nothing especially inconsistent in Mr. Mainwaring's behavior.

But there was something upsetting about it. She so wanted him to be perfect. Helen had long ago lost faith in the people of her class, both male and female. But he had seemed different. Despite the fact that he looked stern and almost morose at times, she had seen humor, kindliness, and intelligence in him. She had dreamed that he was like her, dissatisfied with the rigidity of the code of behavior by which they were expected to live, eager to find out some of the deeper meanings of life that must be hidden behind the superficiality. And, of course, she liked to believe that the man to whom she was so strongly drawn physically was worthy of her regard.

Helen dreaded now to find that he was really no different from any other man. It would be almost impossible, of course, for him to fall in love with the girl he thought she was. But sometimes it was pleasant to dream that the impossible could happen. Now the afternoon had been somewhat spoiled for her. She did not know whether she still wanted to see him. It would be painful to discover that perhaps her suspicions were true, and that he was interested only in the rather interesting physical relationship that had budded the day before.

Yet she knew that she had to go. Tonight he would know the truth. For the rest of her life, long after he was married to Melly, perhaps, she would wonder what would have happened had she gone to meet him. It was altogether possible, of course, even probable, that he would not come. He must have a great many social commitments with which to fill his afternoons. She would go and consider herself fortunate if he did not appear.

William Mainwaring was in a similar quandary for different reasons. He had suffered a half-hour of guilt and remorse as he had walked home across the fields the afternoon before. He should not have gone to see her. Meeting a young girl alone in the woods was a potentially dangerous situation under any circumstances. In his case it was perhaps doubly so. He was unhappy; for almost a year he had been separated from the woman he loved and would never possess, and he had recently been reminded very forcefully of the fact. He was lonely and felt more so among these strangers who would not leave him to his own solitude.

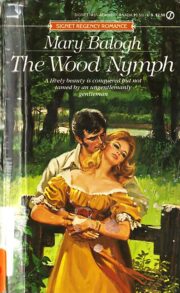

"The wood nymph" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wood nymph". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wood nymph" друзьям в соцсетях.