I pulled her into my arms again. She giggled, then kissed my earlobe, then my neck. “You are so beautiful,” she said. . and for the first time in my life, the words didn’t make me cringe or blush or feel like a fraud. For the first time in my life, I thought they could be true.

I spent a lot of time thinking about what to wear to the first meeting at the fertility clinic. My clothes, I knew, would make a statement. Too fancy and it would look like I was desperate — or, worse, like I didn’t really need the money; too casual, and it would look like I didn’t care.

I stood in front of my shallow closet, finally taking out a black dress made of a forgiving, stretchy material. It wasn’t, technically, a maternity dress, but it had enough give that I could wear it through the winter if things went as planned.

I slid the black dress off its hanger and sat on the bed with a sigh.

“Just put it on. It’s fine,” said Nancy, who’d agreed to watch the boys while I made the trip to the clinic, sparing me the sixty dollars a sitter would have cost. When I’d asked if she was sure she’d be okay, she’d snapped, “Don’t be silly. I like kids.” Instead of pointing out the ample evidence to the contrary, the way she always called Spencer “Frank Junior Junior,” instead of remembering his name, and declared that she and Dr. Scott were “childless by choice,” I thanked her, then asked her if she could come a little early and help me figure out what to wear.

“It’s not fine,” I said, holding the dress up against me. It felt like I was going on a date, only instead of getting dressed up, fussing with my hair and my makeup, hoping that the man I’d be meeting would like me and find me pretty and smart and interesting, here I was, seven years after I’d gotten married, doing the same thing, only it would be a woman doing the evaluating. And women, as any woman will tell you, are much tougher on themselves and on one another than men would ever be.

I slipped the dress over my head, slid my feet into the low-heeled black pumps I wore to church, and studied myself in the mirror. I thought I looked all right. Maybe this lady, this India Croft, would think that my woven straw handbag (ten dollars at Target with my employee discount) was deliberately whimsical, and wouldn’t guess that I’d picked it because it was the only purse I had that hadn’t been chewed on or spat up in, survived a spilled bottle, or housed a dirty diaper.

“You look fine,” Nancy repeated, and smoothed her own highlighted hair, giving herself an approving look in my mirror. My sister had arrived at the house that morning with Tupperware containers full of various organic and sprouted things. There were soy-cheese quesadillas, goji berries, a pomegranate and a protein shake, plus her very own plates and an aluminum water bottle. “You know about the toxins in plastic,” she’d said, frowning at the sippy cup Spencer was sucking. I’d murmured something about replacing the boys’ cups and plates soon, thinking that on my ever-evolving to-do list, that wouldn’t even make the top hundred.

I went to the kitchen for my car keys and a mug of mint tea. I would have preferred coffee. I hadn’t slept well the night before and was worried about getting drowsy behind the wheel. But as an expectant mother-to-be — I hoped — I knew enough not to show up with coffee on my breath.

“Be good,” I told the boys, who’d been bribed with an extra half hour of Go, Diego, Go! “Listen to Aunt Nancy. She’s the boss while Mommy’s gone. Spencer, did you hear me? Do you understand? And Frank Junior, how about you?” I repeated their names, in part so they’d acknowledge my seriousness, in part to increase the chance of Nancy’s remembering them.

“Just go already,” Nancy ordered as I rifled through my purse. There was my wallet, a tube of lipstick, my Mapquest directions, the list of questions I’d printed out at the library, huddling in front of the printer so that nobody could see what I was doing. I knew the longer I hung around, the more likely it would be that the boys wouldn’t let me leave, so I walked to the car and started driving.

Two hours later I was sitting in the Princeton Fertility Clinic. The clinic director, Leslie, trim and brisk in her suit, had walked me back to a room that must have been specially designed for just this moment, when a prospective surrogate and the woman who’d be paying the bills (buying the baby, I kept thinking, and trying not to think) would first set eyes on each other. The walls were the peach of melting sherbet, and there was a painting of a mother gazing tenderly at an infant in her arms. A love seat was upholstered in a light golden fabric. I gave it a quick pat, then a longer one, enjoying its softness and its lack of stains, wondering how long it would last in my house.

The coffee table was set with a china teapot, a carafe of ice water with translucent circles of lemon floating on the top. Fanned out in a circle on a plate was a ring of Mint Milanos that it was taking all my willpower to avoid. I’d been torn about dieting. On the one hand, maybe infertile women would want their surrogate to look robust and healthy, with broad shoulders and wide hips that evoked peasants in the field, squatting to give birth without missing a swing of their scythes. Then again, rich people hated fat people, maybe because they thought that being fat was the same as being lazy, or they were afraid of becoming fat themselves. I ignored the cookies and checked out the china instead. The sugarbowl and cream pitcher had a lacy blue-on-white pattern, and the spoons and the tongs resting on top of the sugar cubes were probably real silver.

“Just a few minutes,” Leslie had said before closing the door, but it had already been more like fifteen. I wondered why she hadn’t just left me in the waiting room, the one I’d glimpsed online and had walked through on my way back here. I could understand why the women hiring the surrogates, the infertile ones, might not want anyone else to see them, but as for me, I was just there to do a job, same as if I’d been back working at Target, and in the waiting room at least there were magazines.

Target made me think of Gabe, and thinking of Gabe made me remember the bad patch in my marriage, the part I hadn’t mentioned on the forms. For distraction, I eased a single Milano out of its place and slipped it into my mouth, letting the sugary wafer dissolve on my tongue. I was trying to rearrange the circle so it wouldn’t look like any of the cookies were missing. Of course, that was the moment the door swung open and Leslie and a slender, graceful, beautifully dressed woman walked inside.

I got to my feet as Leslie trilled the introductions. “Ms. Croft, this is Anne Barrow. Annie, this is India Croft.”

She was Ms., and I was Annie. So it begins, I thought. For a moment, the two of us stared at each other. India Croft had the look I expected, a rich-lady look (rich bitch look, I thought, before I could stop myself), like one of the women from those Real Housewives of New York episodes I sometimes watched when Frank was working. I knew better than to tune in when he was home. “Bunch of silly people who think they’ve got problems,” he’d grumble, and I couldn’t deny it, or explain to him that sometimes the problems were kind of interesting, and it was at least fun to look at their clothes and their houses, and feel good that your kids weren’t half as bratty as theirs.

India Croft was white, like I’d expected, with smooth, unlined skin. Her heart-shaped face narrowed to a neat little chin. Her lips were full and glossed, her nose was small, adorably tilted, her brows were perfectly shaped, and, beneath them, her eyes were wide, almost startled. That, I figured, was probably the Botox — lots of the Real Housewives had that exact same expression, like someone had just pinched their behinds. Her hair was somewhere between chestnut and copper, with all the shades in between, long and thick and shiny. She wore a pale-lavender cashmere sweater set — at least, I thought it was cashmere, but, not owning any cashmere myself, I was really just guessing — and a crisp skirt, chocolate-brown with a pattern of loops and swirls embroidered in darker-brown thread across it. I would have never thought to put brown and pinkish-purple together, but it was perfect. The contrast between the pastel of the sweater and the rich cocoa of the skirt, the soft cashmere and the crisp linen, was like something I’d see on a mannequin or in a magazine. Her legs were tanned and bare. She wore dark-brown cork-soled espadrilles with ribbons that wrapped around her slim calves. I could smell her perfume, something flowery and sweet, and that, of course, was perfect, too.

Standing there, my mouth full of Mint Milano mush, sweating in my long-sleeved dress, I felt big as a battleship and just as ungainly. I swallowed, ran my tongue over my teeth, and stepped forward, saying the words I’d rehearsed in the car: “It’s a pleasure to meet you.”

“Hello,” she said. She tugged at one lilac cuff, then the other, shaking that gorgeous hair against her back, and I felt the strangest sensation of being seen. . not seen, exactly, but recognized. It felt as if, somehow, she was able to see me standing there in my cheap dress and my not-right purse and know me, everything I was, everything I hoped for: how I wanted to redo my kitchen and build a little office, that I wanted to buy my sons new winter jackets, that I wanted, someday, to go to Paris, and go to college, to have shelves full of books I’d read and understood, to have an important job. I felt like she saw me not just as a mother or wife or person in a Target pinny who knew how to find the Lego sets and the scrubbing pads, but as myself, loving and complicated and angry sometimes.

“Anne. . Barrow, is it?” she said, in a pleasant voice. I pegged her at forty. A pretty forty, a young-looking forty, a forty who probably watched what she ate and worked out every day, but still, forty was forty, and forty was, in my opinion, a little too late to get started with the whole baby-making thing. I wondered why she’d waited, what her story was, and if I’d ever get to hear it.

“Annie,” I told her, and held out my hand.

After thinking it over for a few days, I’d decided to tell my brothers what Kate Klein had found out, thinking they’d be just as alarmed as I was and that one of them would know what to do.

Trey had been with Violet when I’d called — I could hear her babbling in the background — and he’d told me, in between her trips up and down the slide at the neighborhood park, that I shouldn’t rain on my father’s parade. “It’s America. Everyone gets a second act,” he said after I’d given him the most damning portion of India’s dossier. Which left me with Tommy. I had just bought a ticket for his upcoming show, thinking I’d present the evidence in person, when my cell phone rang. The number on the screen was for Kate Klein’s office, but Darren Zucker was the one on the line.

“How are you doing?” he asked me.

“Fine,” I said.

“Busy?”

“Not really.” I’d been looking at Victorian jewelry that morning, gorgeously worked, ornate pieces, necklaces and engagement rings, the kind of thing I’d want for myself — small and special, the opposite of India’s ostentatious rock.

“You sound busy.” Darren himself sounded vaguely insulted. I softened my tone, reminding myself that he was a messenger, albeit a messenger in goofy glasses, and it wasn’t his fault that India was a liar. A thought occurred. “Would you like to go to a concert with me?”

“What, like a date?” Now he sounded surprised.

“As friends,” I said firmly. I wasn’t interested in Darren, with his limp handshake and his hipster affectations. In addition, he knew exactly how much my father was worth and probably how much I was, too, and, while it wasn’t as if this information was some big secret, knowing that Darren had access to specifics made me want to keep him at a distance. I didn’t like him… but I didn’t like the thought of traipsing through Hoboken by myself, either, and all of my friends had put in their time at my brother’s performances.

“You got a man?” he persisted.

“None of your business.”

“Taking that as a no,” he said cheerfully, and, over my protests, told me he’d meet me in front of my apartment at nine o’clock Friday night.

“So what’s the band called again?” he asked as we walked along a sidewalk in Hoboken.

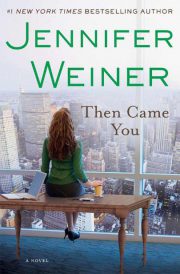

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.