“I guess there’s classes I can take.”

I stifled a yawn. “You don’t need classes. You’ll be a natural.” I could tell that she was worrying, but I couldn’t keep my eyes open. I dozed the whole way to the airport, glad that we were flying out of a different terminal from the one where Frank worked, and I ended up sleeping for the entire trip down to West Palm Beach.

Another car met us at the airport, the uniformed driver waiting by baggage claim, holding a sign that read CROFT. “Have you ladies stayed at the Breakers before?” he asked.

“I have, my friend hasn’t,” said India.

“Well, ma’am, you’re in for a real treat.” He drove us through the gates of a building that looked like the largest, grandest country club in the world. India spoke to the uniformed woman behind the desk, who handed her two keys and two bottles of water. A bellman took our luggage, and India led me to the elevator.

My room — a suite, really — was beautiful, with pale-green carpet and a canopied bed, a deep tub and separate shower in the bathroom, a balcony with a view over a linked complex of swimming pools and, beyond it, the golden sand of the beach. I took off my shoes and lay down on the bed, my cheek against the pillow, which was deliciously crisp and cool. Maybe for a few minutes, I thought, and closed my eyes again. When I opened them again it was nine o’clock the next morning, and there were two notes that had been slipped under the door; one from housekeeping, apologizing for not being able to give me turn-down service the night before, the other from India. Call me when you’re up, Sleepyhead!

“I’m so sorry,” I told her twenty minutes later. At her instructions, I’d put on my swimsuit, then a cover-up, one of Frank’s button-down shirts. We were having breakfast by the pool: eggs Benedict, fresh-squeezed orange juice, a basket of muffins and croissants. I’d looked at the prices, then shut my menu fast and tried to tell myself that maybe the prices were in Monopoly money, or some kind of currency used only in this hotel that had no relationship to actual dollars and cents. Waiters in white shirts and green pants or skirts hovered, waiting to swoop in the instant we needed something: more water, more coffee, more tiny bottles of honey and jam for the croissants.

“Please. I feel terrible that I had no idea how exhausted you were!” She looked at me earnestly from under the deep brim of a straw sunhat tied with a jaunty pink ribbon that matched her dress. “You have to take care of yourself.”

“I’m sure the baby’s fine,” I said.

She waved one freshly manicured hand. “I don’t care about the baby. I mean, I do care about the baby, of course I care about the baby, but I care about you more right now.” She gave me her dazzling smile. “You’re not just the Tupperware, you know.”

“I know,” I muttered, feeling guilty for ever having doubted her, for comparing her to the scrawny, ancient, resentful wife in some book that I’d read.

“So here’s the plan,” she said. “You’re getting a prenatal massage at two…”

“Oh, India, really, I’m fine.”

She continued as if I hadn’t spoken. “And then a facial and a mani-pedi, and I’ve got a car taking us to Joe’s Stone Crab at seven — it’s a little bit of a drive, but it’s supposed to be the place down here, and we’re not leaving until we eat some Key lime pie.”

“That sounds amazing,” I told her. . and then, feeling shy, I said, “but first, can I go for a swim?”

She indicated the ocean like she’d grown it herself. “Go on.”

I floated in the warm, salty water, the skirt of my maternity suit flapping out around me as the waves lifted me up and lowered me down. I wondered how the boys were doing, how Frank was managing without me. . then I decided that everyone would be fine; that I was here, and I should try to enjoy it.

I rinsed off in my room, then went down to the spa, where I half dozed through a blissful afternoon of being tended to, four hours where all I had to do was lift my arms or close my eyes or tell the masseuse how much pressure I liked. All I had to wear for dinner was my plain old black dress again, but when I got back to my room there were shopping bags arranged on the bed, clothes peeking out of pink and pale-blue tissue: a sundress made of pale yellow linen, a skirt, and a few scoop-necked jersey tops, the same kind of flipflops India had worn, all with the price tags cut so that I couldn’t see how much they’d cost.

I let the crisp fabric of the sundress fall over my shoulders and hips and smoothed lotion from the hotel’s little bottle on my skin, then took the elevator down to where India was waiting for me in the lobby. There was another car outside that took us to South Beach. The restaurant was big and crowded, full of groups that all seemed to be celebrating something. Over dinner — caesar salad, warm rolls, crab legs for both of us — India told me her story — how she, too, had grown up without much; how she’d gone to Los Angeles to try to be an actress, how she’d moved to New York City to work in public relations, how she’d met Marcus in a Starbucks, of all places. “What was that like?” I asked. What I really wanted to ask was, how had she found the confidence to go to a city all the way on the other side of the country, to get herself the kind of job I hadn’t even known existed, to turn herself into the kind of person Marcus wanted? She was so much smarter than I was, so much more clever, and I listened closely as she explained how she’d figured out what publicists were and what they did; how she’d made connections and networked with the right people to get an internship, then a job.

At the end of the meal, over decaf coffee and a slice of that tart, rich Key lime pie, India bent her head, suddenly shy. “I bought you something,” she said. “Merry Christmas.” She handed me a little velvet box. Inside was a necklace, a gorgeous green stone suspended on a shimmering length of silver chain. “Emerald,” she said. “It’s the baby’s birthstone. I wanted you to have something so you can always feel close to her. Or him.” She smiled — she and Marcus had decided not to learn the baby’s gender, but we were both secretly convinced that I was carrying a girl.

My throat tightened. No one had ever given me jewelry, except for my engagement ring, and of course I had nothing for her except the card and the homemade raspberry jam I’d sent to her apartment before Christmas. “Oh, India. It’s beautiful, but it’s way too much.”

“No,” she said. Her eyes were shining. “No, it is not too much. What you’re doing for Marcus and me, there’s nothing we could ever pay you to thank you enough.”

We hugged, and I told myself to stop being so critical, to just enjoy the night, the sweet taste of fresh crab, which I’d never had before, and how lovely it was to slip deeply into those cool, crisp sheets in an immaculate room and sleep in as late as I wanted, to wander on the beach for hours, the sand warm and firm against my bare feet.

“Now listen,” she said, as we drove back to the airport. “If you start feeling overwhelmed or tired like that again, you call me, no matter what. I’m finding you a cleaning lady, and don’t even try to talk me out of it. It’s ridiculous that you’re scrubbing floors.”

“Lots of people do,” I pointed out.

“Lots of people don’t have a choice. But you do. So no arguments.”

“Thank you,” I said, for possibly the hundredth time in the last two days. The words were completely inadequate, but what else could I say? That she’d changed my life? That, looking at her, I was starting to think about how things could have gone differently for me, and what might still be possible? That it was exhilarating and terrifying at the same time?

“Travel safe,” she said, hugging me. . and in that moment I believed that if everything had been equal, if we’d met in school or working some job or pushing our new babies on swings in the playground, that India Croft and I could actually have been friends.

I made the trip in reverse: car to the West Palm Beach airport, plane to Philadelphia, car back to my parents’ house to pick up the boys. “They were angels,” said my mother, but she looked hollow-eyed, like she couldn’t wait to go back to her couch and catch up with her TV friends. My house hadn’t been trashed — there were no piles of dirty dishes or dirty laundry, no chair that had been flung through the television set — but Frank hadn’t done much cleaning. Things appeared to be exactly as I’d left them after Christmas dinner, the platters still in the drainboard next to the sink, the pine cones still in the middle of the dining-room table. Frank helped me bring the suitcases inside. Then he stayed out of my way, not offering to help as I fed the boys dinner and got us unpacked.

Finally, at eight o’clock, with the boys washed and brushed and tucked into their beds, I stood at the doorway of the family room. Frank was once again planted in front of the television set, watching some comedy with a cackling laugh track. I planted myself in front of the screen and stood there until he clicked it into silence.

“Nice necklace,” he said — the first words he’d spoken other than a muttered “hello” when I’d arrived.

I felt myself blushing, but I didn’t back down. “India gave it to me. It’s the baby’s birthstone. So I can remember her.”

“Must be nice,” he said sarcastically. “A friend who can give you presents like that.”

I felt like throwing something at him, but I didn’t want to wake up the boys. “I don’t care about jewelry! For God’s sake, Frank, all I wanted to do was get us out of this mess, get us a little extra money…”

“Well, you did it. Good for you.”

“Frank,” I said. My voice cracked. “What do you want me to do? I can’t undo this,” I said, running my hand over my belly, so he’d know what I was talking about.

“I don’t know.” He bit off each word, and I realized that he wasn’t just angry, the way I’d seen him a few times over the years, when the bill collectors would call, or the time he’d been passed over for a promotion. He was way past angry. He was furious. . and it scared me.

He got to his feet. “I’ve been thinking maybe I’ll go stay with my mom for a while.”

“You do that.” The words were out of my mouth before I could think about them, but it only took me a moment to realize that this was the right choice, maybe the only choice. Angry as he was, I didn’t want to be around him, and I didn’t want the boys around him, either.

“This was a mistake,” he said, walking past me without sparing me a glance. Questions swirled in my head: Would he come back? Would he see the boys? Was this a separation? Did he want to get divorced? But I didn’t ask any of them. I just stood there, frozen, unbelieving, as he climbed up the stairs, packed a bag, climbed into the car, and drove off into the dark.

It started out a day like any other chilly, gray-sky April morning. I woke up feeling Marcus’s lips on my forehead, hearing the soft clink as he set down a cup of tea beside me. “How is the mother-to-be?” he asked, and I smiled. Neither of us was trying to pretend that the situation was anything other than what it was, but Marcus still treated me like I was expecting. We had the ultrasound pictures stuck to our refrigerator with a magnet; we sent Annie downloadable recordings of our voices reading the baby stories and singing lullabies, and kept a calender marked with red Xs through each day before the baby’s arrival hanging on my dressing room door.

Once Marcus was showered and dressed and off to work, I padded to my dressing room and pulled on the workout clothes I’d laid out the night before — tights and running pants, a long-sleeved Under Armour shirt with a fleece jacket on top of it.

My trainer met me in the lobby, and we jogged across the street, across the wide sidewalk through the gap in the stone gate and into the park for the usual ninety minutes of torture. Back at home, my breakfast was waiting for me on a tray: a white china plate covered with almonds, dried apricots, a peeled, cored apple cut into slices so thin they were translucent, and a hard-boiled egg. I looked longingly at Marcus’s soaking tub before skinning off my sweaty clothes. It wasn’t as if my shower was Spartan: the water assaulted me from a half-dozen nozzles and there was a marble ledge, specially designed so I’d have a place to prop up my foot while I shaved my legs. Some couples had his-and-hers sinks. Marcus and I had his-and-hers bathrooms. “It’s the secret of a happy marriage,” I’d told Annie. “That, and Viagra.” The truth was, Marcus liked to visit me in my bathroom, knocking on the door in his bathrobe. Sometimes he’d slip into the shower with me, getting his hands slick with soap and running them over my body, and sometimes this would lead to sex, but, more often, he’d just pull up the chair from my vanity and sit by the shower, talking about nothing and everything, his children, his colleagues, the next trip we’d take. At first I’d been shy about letting him see me backstage — he didn’t need to know that I used concealer or plucked my eyebrows — but, after a while, I found that I genuinely enjoyed his company, and I looked forward to those mornings more than any other part of the day.

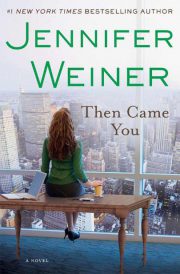

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.