My mother had been born Arlene Sandusky in a suburb of Detroit in 1958. She’d married my father at twenty-three, then moved to New York, where she’d had three children and become an enthusiastic baker of cookies and trimmer of Christmas trees, a woman who liked nothing better than taking on some elaborate holiday-related project — assembling and frosting a gingerbread house, or running the schoolwide Easter egg hunt. In the wake of her association with the Baba, she’d ditched her traditions and her Martha Stewart cookbooks. She’d grown her hair long and let it go gray. She’d swapped her designer suits and high heels for embroidered tunics and thick-strapped leather sandals, and traded her Bulgari perfume for a mixture of essential oils that made her smell like the backseat of a particularly malodorous taxicab, sandalwood and curry with hints of vomit. She’d gotten a belly piercing that I’d seen and a tattoo that I hadn’t — I hadn’t even been able to bring myself to ask where or of what—and, eventually, she began slipping the Baba tens of thousands of dollars. When my father’s accountants finally started to ask questions about what the Order of New Light was and whether it was, in fact, a tax-free C corporation, she’d announced her intentions to get a divorce and follow the Baba to Taos, where he was building a retreat offering intensive yoga training, raw cuisine, and a clothing-optional sweat lodge.

I came home from school one afternoon and found luggage lined up in the hall and my mother in her bedroom, packing. “I am renouncing the meaninglessness of the material,” she said, sitting on top of her Louis Vuitton suitcase to get the zipper closed. I pointed out that the meaninglessness of the material did not seem to cover the great quantity of Tory Burch tunics and Juicy Couture sweat suits that she had packed.

“Oh, Bettina,” she said, in a tone that mixed scorn and, unbelievably, pity. “Don’t be so rigid.” She kissed me, taking me into her arms for an unwelcome and musky embrace.

“Be good to your father,” she said, smoothing my hair as I tried not to wriggle away. “He’s a good man, but he’s just not very evolved.”

After that, my mother communicated by letters and postcards, while my father became Topic A in the gossip columns and, when he started dating again, prey for single ladies of a certain age. There was the magazine editor famous enough to have been skewered in a movie, played by an actress who, in my opinion, was ten years too young and significantly too pretty to be a plausible standin. She was followed by a real-estate mogul with a face permanently frozen into a look of startled puzzlement, then a newspaper columnist, similarly Botoxed, who’d made a career out of being bitchy on the Sunday-morning political chat shows. In that realm of gray-suited, gray-faced men, it turned out that even a not-terribly-attractive fifty-two-year-old could pass herself off as a babe if she wore pencil skirts, kept her hair dyed, and made the occasional reference to oral sex.

Even when my father was technically attached, it didn’t stop other women from trying. There would be a hand that lingered on his forearm, a cheek kiss that ended up grazing his lips, a business card with a cell phone number scribbled on it, pressed into his palm at the end of a night. My father had resisted them all, the waitresses and the young divorcees and the actress-slash-models… which was why it made no sense that he’d fall for this hard-edged, new-nosed, fake-named “India,” who was no more in her thirties than I was the winner of America’s Next Top Model.

“Are you worried she’s going to spend our inheritance?” Tommy asked, spinning the wheel of his lighter.

“It’s not about the money,” I said, ignoring the twinge I felt at the thought of this stranger squandering what should have been mine. I had a trust fund, worth ten million dollars, that I’d be able to access on my twenty-first birthday, which was coming in two months. My father had already told me he’d buy me an apartment after I graduated, in whatever city I ended up working. Needless to say, I had no student loans. I’d most likely get a job that offered health insurance, and I’d inherited all the clothes, shoes, furs, and jewelry that my mother hadn’t sold before decamping to New Mexico. Even if my father married some grasping bitch (unlikely) and didn’t sign a prenup (even more unlikely), my brothers and I would be fine. I knew, for example, that my dad had already set up a trust for Trey’s daughter, Violet, and that he’d bought new amps for Dirty Birdy, which specialized in thrash-metal covers of female singer-songwriter ballads.

I ground my cigarette under my heel. “It’s not the money, it’s the principle of the thing. This woman just thinks she can waltz on in here and have. .” I waved my hands out at the lawn, which rolled, lush and green, down a gentle slope to the ocean. “… all of this, and she didn’t earn any of it.”

“Well, when you think about it,” Tommy said, “we didn’t exactly earn any of it, either.”

“We survived Mom and Dad,” I reminded him. I’d given the matter of what we were and were not owed considerable thought. . sometimes while I was walking into what passed for downtown Poughkeepsie so my roommates wouldn’t see me being picked up by a driver.

“I think we need to give her a chance,” said Tommy.

“Do we have a choice?” I inquired, and Trey, who’d been looking at his BlackBerry again, shook his head and said, “We do not.”

I sighed. Tommy finished his cigarette. Trey put his telephone back in his pocket. “Dad knows enough to be careful.”

I didn’t answer. My brothers had both been away at school when my mom had left. I’d been the only one home. What happened to my dad hadn’t been dramatic. . he’d just gotten quieter and quieter, more and more pale. Prior to my mother’s departure, he was rarely home before eight o’clock at night, but, after she left, he started returning at five, then four, then three in the afternoon, locking the bedroom door behind him, saying that he needed a nap. My mother had left in September. By Christmas he’d stopped sleeping. He’d take his naps, then sit up all night by the windows, not eating, not drinking, not talking. I’d ask him, over and over, if he was all right, if he wanted anything. He’d shake his head, trying for a smile, unable to manage more than a few words. I’d talked about therapists; I’d mentioned antidepressants — half the kids I knew had been on some kind of medication for something at some point in their lives. I’d called my brothers, who’d told me — brusquely, in Trey’s case, kindly, in Tommy’s — that Dad would be fine, that this was just something he had to get through. Easy for them to say. They weren’t the ones who saw him frozen in an armchair, underneath a de Kooning on one wall and a Picasso etching on another, not noticing the art, or the sunsets over the park. They didn’t see the way his pants sagged around his shrinking waistline and flapped around his diminished legs, or the silvery stubble glinting on his chin.

One dark day in February, I came home from choir practice and found every dish in the kitchen smashed and my father shin-deep in the shards of china and porcelain. My parents had had half a dozen sets of dishes, and the mess was considerable. My father stood there, blinking, a dish with a blue bunny painted in its center in his hand. When I ran to him, I could feel the jagged edges of shattered bowls and plates and coffee cups biting at my ankles, ripping at my tights. “Daddy?”

He gave me a wavering smile. “I. . well. That felt better. That felt pretty good.” Together, we swept up the mess, filling a dozen garbage bags with the wreckage. Things improved after that. By spring, he was, as he put it, “stepping out,” whistling as I attached cuff links to the starched cuffs of his shirt, taking women to the benefits and balls my mother used to dread.

I picked up my cigarette butt and slipped it in my pocket, a thief removing the evidence, while I wondered about India’s strategy: whether she could get my dad to marry her, whether she was young enough to seal the deal by getting pregnant. I would watch. I would wait. I would do what I could to keep my father safe. India struck me as a formidable enemy and the money meant that the stakes were high. . but I was my father’s daughter, and I loved him very much.

You’ve been spotting, hon?” the nurse asked.

I nodded mutely. Spotting was what I’d told my obstetrician on the telephone that morning, spotting was what I’d written on the forms in the office that afternoon, but I was actually bleeding, not spotting. After three failed in vitro attempts, I knew the difference.

“Let’s take a look. Lean back, now. Deep breath.” I shut my eyes as she pushed the ultrasound probe inside me. Marcus squeezed my hand, and I thought how this office was the one place, maybe one of only a few in the world, where it didn’t matter what he was, that he’d sold his first business at twenty-five and started his own hedge fund at the age of thirty-one and now, twenty-six years later, had hundreds of millions of dollars and clients all over the world. Here, we were just another infertile couple, a little desperate, no longer young, flipping through limp magazines in the waiting room, hoping that we’d win the prize.

I knew, though, even before I looked at the screen, that it hadn’t happened this time. It was just like the previous two rounds: a positive pregnancy test, then rejoicing, even though I knew it was too soon. A few days later, a blood test had confirmed the pregnancy but revealed a low hCG count. hCG, as I’d learned, was human chorionic growth hormone, the stuff that shows up in your blood and lets you know that the embryo’s developing. The level’s supposed to double every forty-eight hours. In my case, that had never happened. The hCG number would rise, then stall, and then start dropping. A week or ten days later, the bleeding would start and I’d come to this office for an ultrasound, the crooks of my arms bruised from blood draws, and the doctor would tell me what I already knew: that there was a fertilized egg that had started to grow and then stopped. There was no heartbeat. You lose. Again. Blighted ovum, the Internet called it, though my doctor had never used those words, or any words that sounded like they assigned blame.

“I’m sorry, hon,” said the nurse. I’d seen her before, a no-nonsense lady in her fifties with short hair dyed blond and kind eyes. “Doctor will be right in.”

She pulled out the probe, pressed a pad against me, and left me and Marcus alone. It was sunny outside the windows, a perfect May morning, the whole city in bloom, from the daffodils in the planters in the median on Fifth Avenue to the trees in Central Park. “Shit,” I said, and shut my eyes. “Shit, shit, shit, shit, shit.”

“Oh, babe,” said Marcus. He leaned forward to kiss my cheek, letting me feel the warmth of his skin and smell the cedar and vetiver in his cologne. He was crying a little. Perversely, that made me feel better, like I hadn’t forced him to do this. Marcus was in his late fifties, with three grown children, all of them out of the house and reasonably self-sufficient. He would have been well within his rights to tell me he was done with babies. But he hadn’t. Marcus loved me. He wanted me to have everything I wanted. “We can try again next month, if Dreiser says it’s all right.”

Dreiser was Dr. Theodore Dreiser of Harvard and Columbia, acknowledged by New York magazine and everyone else who mattered as the top reproductive specialist in the city. I shook my head.

“No more.”

“Listen. You don’t have to make up your mind right now. We’ll get some lunch, you can have a glass of wine.”

I smiled. These days, the only times I drank were after doctors’ visits such as these. . or after the D and C that would follow. Then I pulled the cotton gown down over my bare knees (tanned, hairless, absolutely jiggle-free, looking better than they had when I was a teenager) and sat up. “I’m not getting any younger.” This was true. I might have had the body of a woman in her twenties — I certainly worked hard enough at it — but I was forty-three years old, even if Marcus thought I was thirty-eight. “I don’t think we’ve got any more time to waste.”

Marcus, impeccable in his made-to-measure shirt and silk tie, started to answer when the door opened, revealing the doctor, slim and erect in his white coat, with a neatly trimmed salt-and-pepper beard, oversized Roman features, liquid brown eyes, and an expression of consternation. He didn’t like being a loser any more than I did. It meant that New York magazine and the ladies who mattered, the ones who could pay for treatments even after their insurance ran out, might start sending their friends somewhere else. “Guys, I’m so sorry,” he said. Marcus squeezed my hand again. I turned my face toward the wall and finally let the tears come, the ones that had been threatening since the spotting — bleeding — had started.

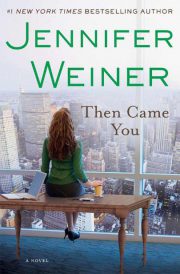

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.