“Now I am.” I shut my eyes for a moment. If there’s one thing I never asked for, it was to sell my soul to Emily Wallace.

Emily turned her head to glance around, as if to make sure no one was there to hear her. Then she leaned in and said in a low voice, “I want to go to your party tonight. You know, the one that was listed in the paper. Also, Petra’s coming. And Ashley. Do not get us kicked out again. That is not acceptable.”

Emily flashed me her pearly white teen-model smile. If she’d been trying to sell me toothpaste, I might have even bought it.

I considered telling her that I didn’t even know if I was going to my party tonight—didn’t know if I wanted to, didn’t know if I was allowed—but that was, frankly, none of Emily’s business. “That’s it?” I asked.

She pursed her lips, like it hadn’t occurred to her that she might wrangle yet another payment out of me from this one good deed and she wanted to make sure she used it wisely. At last she asked, “So did you actually try to kill yourself? Or did that weird bitch just make up the whole thing?”

Silently, I held up my left arm, wrist facing Emily. She crossed her arms and kept her lips squished together as she examined me for a moment, sizing up those three perfect scars. Finally, she said, “You know that you’re supposed to cut down to kill yourself, right? You did it wrong.”

I looked at Emily and thought about what would have happened if I’d cut the other way. Or what wouldn’t have happened. Char wouldn’t have broken up with me. Alex wouldn’t be mad at me. Pippa wouldn’t hate me.

And I would never have met Vicky. I would never have had my first kiss. I would never have worn rhinestone pumps. I would never have heard Big Audio Dynamite. I would never have discovered Start. I would never have known I could be a DJ.

Emily Wallace didn’t know what she was talking about. She never had.

You did it wrong, she said.

“No,” I said to her. “I didn’t.” Then my mother’s car pulled up in front of the school, and I turned my back on Emily, and I walked away.

18

“You could have told us,” Mom said as she drove me to Alex’s fair. Before my mother picked me up, Mr. Witt had called her to reveal the identity of the blogger and reassure her that Glendale High was once again, as promised, a Very Nice School. “You could have shown that diary to your father, or me, or Steve, and we would have put an end to this long ago.”

You couldn’t have put an end to it, I wanted to tell her. You don’t have the power of Emily Wallace.

“Don’t you think having a conversation about what was going on would have been more productive than ruining Alex’s school project?”

“I thought I was helping her,” I said. “At the time.”

“And now?” Mom asked.

“Now … no. I don’t think that anymore.”

Mom nodded. “You’re a smart cookie, Elise.”

I had always loved when she said that to me, because she was one of the only people in the world who didn’t make it sound like a put-down.

“So can I stop being grounded?” I asked.

Mom laughed lightly as she paused at a stop sign. “No matter how much you’ve seen the error of your ways, you really hurt your sister. And you really hurt this family. I can’t let you off the hook so easily. It wouldn’t be fair. You can’t be ungrounded, but here’s what you can do: you can come home.”

The idea of walking back into my mom’s house after a week away, lying in my big bed there, wrestling with Bone and Chew-Toy, sitting with Alex and Neil and Steve around the breakfast table, having Dinnertime Conversation … it made me smile.

“I’d like to come home,” I said. “I’d like that a lot.”

Mom parked the car at Alex’s school’s parking lot, and together we walked into the fair.

At Glendale East Elementary School, everyone was in high spirits. The soccer field was filled with the second graders’ booths. Older kids ran around selling popcorn and cotton candy. There was even a bouncy castle. Steve, Neil, and Alex had already arrived, and they were standing at Alex’s replacement booth, which consisted of a few cardboard boxes duct taped together with a handful of quickly scrawled poems sitting on top of them. It was nothing like the real poetry castle. It was more like a condemned poetry shack. Looking at it made my stomach turn.

“Hey,” I said, bending down to address my little sister. “Can I talk to you for a second?”

Alex shook her head and hid behind Mom’s legs. I briefly wished that my genetic code did not include quite so much stubbornness.

“Just hear your sister out, Alex,” Mom said, stepping aside. “Let her say her piece.”

Alex scowled and followed me a few paces away from her booth. She was tightly clutching one of her favorite Barbies, glaring at me like I might lunge out and start tearing her doll limb from limb.

“Alex,” I said, “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have ruined your poetry castle. I’ll never do anything like that again.”

She pretended to ignore me, mumbling to her Barbie as she made it crawl across a nearby tree branch, clearly playing some imaginary game.

This gave me an idea.

“You know that game you play, Underwater Capture?” I asked her.

“I can’t play it anymore.” Those were the first words my sister had spoken to me since last Friday. “Because of the new couch.”

“But you know the evil sea witch in Underwater Capture?” I pressed on. “The one who gets inside the dolls’ heads and turns them all evil?”

Alex nodded once, not looking at me.

“That’s like what happened to me, Alex.”

She looked at me then, her forehead wrinkled.

“It wasn’t a real sea witch,” I explained. “It was people I know. But that’s how it felt—like all these bad thoughts were in my head, and I didn’t know they weren’t really mine. And that’s why I wrecked your castle. It wasn’t the sea witch’s fault, since I’m the one who did it. But I did it because I was listening to her too much. Does that make sense?”

I couldn’t tell if I had taken this analogy too far, or if seven-year-olds even understand analogies, but after a moment, Alex nodded. “I’m sorry you had a sea witch,” she said.

“Me, too.”

“But—” She shook her head, as if shaking herself free from feeling any sort of sympathy for me. “You ruined my poetry castle. That’s mean, Elise. That’s the meanest thing anyone has ever done to me. And I know sea witches are evil, but I don’t care why you did it. You shouldn’t have done it.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m so sorry, Alex. I know.”

But it was too late; Alex had already stalked off.

And after that, I didn’t know what to do. What do you do when you say sorry, but that still isn’t enough?

I walked slowly around the fair. I saw a post office and a cookie store and a booth that sold worms and caterpillars, although the second grader in charge told me they were all out of caterpillars.

I smiled at all the kids and told them what good jobs they had done. But inside, I felt like my heart was breaking. Because Mom was right: Alex’s booth would have been the best one.

The thing was, Alex’s replacement booth was no worse than half the other ones out on this field. In a week, she had thrown together something that was just about as good as what her classmates had done. Just about as good as theirs, but a fraction of how impressive she was capable of being.

Because of me, and what I had done to her.

In that moment, paused between a booth that sold papier-mâché flowers and a booth advertising mud sculptures, I knew this, suddenly but finally: I wanted to DJ my party tonight. Not to prove Char wrong, not to put Emily and her friends on the guest list, not for anything like that. Simply because Alex deserved to be the best that she could be. And I did, too.

After the fair was over and all the booths had been broken down, Mom and Steve took me, Alex, and Neil out for pizza.

Pizza is a rare treat in the Myers household, reserved for special occasions like winning art contests, performing the lead role in the school play, definitively triumphing over the oil industry, or making it through the most traumatic second-grade school fair in all of history.

“Let’s get it with pepperoni,” Alex said as we headed to the parking lot.

“Let’s get it with maple syrup,” Neil said.

“Let’s get it with pepperoni and maple syrup,” Alex said.

We would get it plain, and with soy cheese. We always did.

Alex and Neil rode in Steve’s car, while I traveled to Antonio’s Pizzeria with my mother.

“Mom,” I said as we left the school, “I know I’m still grounded. But—can I be a little ungrounded?”

“Tell me what that means, and I’ll tell you yes or no.”

I took a deep breath. “Can I get, like, a furlough, just for one night? Tomorrow I swear I’ll go back to being grounded. But tonight I’m … supposed to DJ a dance party. At that warehouse where Dad picked me up last night.”

Mom sighed. “I know.”

“You do?”

“Your father told me he saw it listed in the paper.” She glanced at me sideways, and my face must have conveyed my surprise, because she said dryly, “Just because we’re divorced doesn’t mean we don’t know how to exchange a civil e-mail, you know.”

“So can I?”

Her fingernails drummed against the steering wheel, and her voice was tense as she answered, “You shouldn’t be out of the house that late at night. You’re way too young to drink—”

“But I don’t drink,” I protested.

“—and I can’t have you hanging out with drunk people either. Especially not ever drunk people who are driving you somewhere.”

“I don’t,” I said. “I wouldn’t.”

“It terrifies me to think of you wandering the streets alone at night, because you’re a sixteen-year-old girl and you’re an easy target. And I don’t want you spending your time with so many people who are so much older than you, because I worry they are going to take advantage of you, just because you’re young. I don’t think you appreciate how recklessly you’ve been acting, and how lucky you’ve been so far. I can’t let this kind of behavior go on.”

So this was it, then. The moment when my mother forbade me to go back to Start. I wanted to feel shocked, but instead I felt only sadness.

And now, what would I have?

Well, I would have Sally and Chava. And that was something worth having; at least, more worth having than I had known.

I would have the respect of Emily Wallace and company. I didn’t expect that they would ever honestly like me, but that was okay; I didn’t expect to like them either. But I also didn’t believe that they would offer to give me a makeover any time soon.

I would have Vicky and Harry, and maybe someday, if she could ever forgive me, Pippa, too. They weren’t nightlife friends. They were real-life friends.

I would have memories of when I was golden.

I would have less than I had two weeks ago. But more than I had in September.

“But,” Mom was saying, as she turned onto the street that Antonio’s was on.

“But,” I repeated, coming back to the present.

“I’m not going to tell you that you can’t go.”

I blinked. “You’re not?”

She scanned the street for a parking space. “More than anything else that I don’t want, I don’t want to keep you from doing something that you love so much. I can’t do it. It wouldn’t be fair.”

I felt tears pricking my eyes, but not the same sort of tears that I had cried last Thursday night, coming home from Start. “Thank you,” I whispered.

“One condition,” Mom said, finding a spot and backing into it. “Your father will need to drive you there and home.”

I rubbed my eyes to clear them. “You’re kidding, right? You think Dad actually wants to hang out in a warehouse nightclub until, like, three a.m.?”

“No,” she said. “In fact, I know for sure that he doesn’t. But he wants to know you’re safe. We both want to know that you’re safe, always. And if that means your father stays up until sunrise sometimes, then that’s what we’ll do.” I opened my mouth, but she said, “Don’t even try to argue, or you’re not going anywhere.”

“Okay,” I said in a small voice. “It’s a deal.”

She turned off the car and faced me. “I’m really disappointed in you, Elise.”

“I know.”

“Not just because of how you treated Alex. I really believe you’re in the process of making that right, even if it takes time. But because of how you treated me. If you want to do something like go for a walk in the middle of the night, or party at a nightclub, tell me. I know I’m your mother, but I’m a reasonable person. I think we can work these things out.”

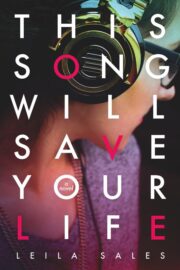

"This Song Will Save Your Life" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "This Song Will Save Your Life". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "This Song Will Save Your Life" друзьям в соцсетях.