‘She’s an informer, here to spy on us.’

‘But why would Rafik, who loves our village so strongly, take in someone like that?’

‘Because…’ He paused, ran one of his big hands along the fine muscles of the horse’s leg and released his hold on her hoof. She bounced up on her toes and nearly kicked over his stool. Pokrovsky stood up straight and rubbed his hands on a dirty rag at his waist. ‘Elizaveta, I’m only a simple blacksmith, you’re the one with the brains.’

She laughed at that, a girlish laugh, and poked her furled parasol into his ribs. ‘Simple you are not!’

With a deep chuckle he led her further into the smithy where he poured her a glass of vodka without asking, and another for himself. He knocked back his drink in one but she sipped hers as if it were tea.

‘She stole my axe,’ he told her. ‘Zenia returned it to me.’

Her brown eyes widened. ‘Why would this stranger do a thing like that, I wonder.’

‘She wanted to chop wood?’ He raised one burly eyebrow.

‘Very funny,’ Elizaveta said dismissively. ‘The question is whether Stirkhov has sent her here to watch us.’

‘Rafik would never take in one of that bastard Stirkhov’s spies.’

‘He would if he wanted to keep an eye on her.’

‘You think that’s it?’

‘It could be.’ She finished her drink with a dainty flourish and let her eyes roam round the tools and forge. She gave a little satisfied nod of her head. Without turning to look at him she said, ‘There’s another package due in tonight, my friend.’

Pokrovsky poured himself another glass. ‘I’ll be there. You can rely on that.’ He drank it down.

‘Someone is coming. A woman.’

Sofia said the words calmly but she felt a jolt of alarm at the sight of a female figure heading towards the gypsy’s house through the last traces of dusk. The habit of fear was hard to break. She was seated on the bleached wooden doorstep, her cheek resting on her hand, her gaze fixed firmly on the village. She was watching the cows being led in from the fields, weary and heavy-footed, and the group of men heading for the meeting in the old church.

The evening had not been easy in the gypsy izba. Conversation was impossible. How could you talk in these bewildering circumstances without asking questions? But if you asked questions someone was forced to give answers and that meant lies. And who wanted lies?

‘Who is it?’ Rafik asked.

Zenia left her seat at the table where she was shredding a pile of dusky leaves, came over to where Sofia was sitting and squinted into the gloom that had settled like dust on the street.

‘It’s Lilya Dimentieva.’

‘Does she have the child with her?’ Rafik asked.

‘Yes.’

Sofia tensed as the woman and child came close, but she needn’t have worried because Lilya Dimentieva showed no more interest in her than she did in the carving of birds on the door lintel above her head. She was a woman in her twenties, small and slender with an impatient face and long brown hair bound up carelessly in a scarf. Her navy dress was neat and tidy, unlike Sofia’s ragged skirt and blouse, but the little boy whose hand clutched tightly to hers was a different matter. He was barefoot and in need of a wash.

‘Zenia, I want-’

‘Hush, Lilya,’ the gypsy girl said sharply. ‘Come inside.’ She gestured to the stranger sitting silent on the step. ‘This is my cousin and she’ll look after Misha. Won’t you, Sofia?’

‘Happily.’ Sofia stretched out a hand to the small boy.

His mother disentangled him from her skirts with a quick, ‘Misha, wait here,’ and disappeared inside the house with Zenia. Sofia and the boy studied each other solemnly. He was no more than three or four, dressed in what looked like a cast-off army shirt cut down into a tunic that was far too big for him.

‘Would you like to share my seat?’ she asked, patting the warm step beside her.

He hesitated, fingering a shaggy blond curl.

She edged over to make room. ‘Shall I tell you a story?’

‘Is it about soldiers?’

‘No, it’s about a fox and a crow. I think you’ll like it.’

He put out a tentative hand. She took it, soft and dusty, inside her own and drew him to share her doorstep where he plopped down like a kitten, but he still kept a small safe gap of evening air between his own body and hers. Already he’d learned to be cautious.

‘I don’t like this house,’ he whispered, his pupils huge in the semi-dark. ‘It’s full of… black.’ He blurted out the last word and then, as if he’d said something wicked, he clapped a hand over his mouth.

Sofia gave a soft laugh and the boy instantly pressed his other hand tight over her lips. She could taste onions on his fingers. Gently she removed his hand.

‘No,’ she reassured the boy, ‘Rafik is a kind man, and it’s just like any other house here in Tivil.’ She didn’t mention the ceiling with the whirling planets and the staring eye. ‘No need to be frightened of it.’

His hand patted her knee. ‘Tell the story.’

She closed her eyes, leaning against the wooden doorpost. She felt the solidity of it all the way down her spine, and was surprised to find Misha leaned with her, his shoulder nestling against her ribs. Behind them in the room she could hear the murmur of low voices. She opened her eyes and smiled at the boy.

‘There was once a fox called Rasta and he lived in a dark green forest up in the mountains among the clouds.’

‘A forest like ours?’

‘Just like ours.’ The high ridge above the valley had been swallowed by the evening darkness but they could both still see it in their heads. Somewhere a fox barked.

‘There,’ she said, ‘there’s Rasta calling for his story.’

With the air around them so still it too seemed to be listening, Sofia began to tell Misha the tale of the Reynard who made friends with the Crow. Before she was even halfway though it, the boy placed his head on her lap, his breathing heavy and slow. She picked a barley husk from his hair. As she stroked his cheek with her fingertips, aware of the child’s warm body on her knee and the glow of the kerosene lamp flickering behind her among the voices, she could almost fool herself she’d found a home.

13

Davinsky Camp July 1933

‘Anna, wait for me,’ Nina called out as she bent to stuff fresh moss into her shoes in an attempt to keep the water out.

Anna lifted her head. Her heart raced.

Anna, wait for me. Those were the last words she heard when Sofia escaped. Anna heard them again as clearly as if Sofia were standing next to her now. They hung in the air, insistent. Wait for me. All these months Anna had worried and fretted and tortured herself with nightmares, imagining every kind of hideous fate for her friend. A slow and painful starvation in the steppes or pitch-forked to death by a farmer or raped by a soldier. Torn to shreds by a bear or savaged by a wolf. Recaptured and sent to slavery in a coal mine or, worst of all, recaptured with a bullet in the head. Recaptured. Recaptured. Recaptured. The word had whirled around her brain.

Wait for me.

Anna looked around her at the women lining up for the exhausting trek back to the camp. It was the end of a long workday, a two-hour march ahead of them, their feet sore and blistered, backs aching and stomachs clenched with hunger. But it was a brief moment of time that Anna always enjoyed. Heads came up instead of drooping between shoulders, scarves were retied and leggings that protected against insect bites in the slimy ditches were stripped off. Work had to be performed in strict silence, but for these brief few minutes the women broke into conversation with each other. To Anna it was as sweet as if they’d broken into song. It wasn’t important whether they discussed that day’s moans or laughed at stupid jokes so hard it set their chests aching, what mattered was that they talked to each other.

‘How’s your cranky knee today?’

‘Much the same, you know what it’s like. What about your leg ulcers?’

‘A bloody pain.’

‘Has anyone got a length of cotton? Look, I’ve torn my shirt.’

‘Have you heard about Natalie?’

‘No.’ A cluster of voices. ‘What news?’

‘She’s had the baby.’

‘Boy or girl?’

‘A boy.’ A pause. ‘Born dead.’

Two women crossed themselves discretely, so guards wouldn’t notice.

‘Lucky fucking bastard,’ Tasha snapped. ‘Dead is better than-’

‘Shut up,’ Nina scolded, taking her place with a shrug of her broad shoulders beside Anna in the crocodile line. It used to be Sofia’s place. Whenever Anna stumbled or fell behind, Nina’s strong hand was there. ‘There’s a rumour going round,’ Nina said under her breath.

‘About what?’ Anna asked.

‘That we’re soon to be put to work constructing a stretch of railway.’ She picked off a fat scab on her arm and slipped it into her mouth for something to chew on.

‘The northern railway?’

Nina nodded and the two women exchanged a look.

‘They say,’ Anna murmured as they started marching, ‘that the railtrack has killed forty thousand this year already.’

Yet always more came, an unending river of prisoners carted across the country in cattle wagons. Each new arrival in the hut raised Anna’s hopes but each time she drew a blank.

‘Have you spoken to anyone called Sofia Morozova? In a transit camp? On a train? In a prison cell? ’

‘Nyet.’ Always the answer was ‘Nyet ’.

Anna’s eyes travelled to the dense wall of copper-coloured tree trunks on either side of the road, a raw scar that raked its way through the forest to another godforsaken camp and then another and another. Was Sofia out there? Somewhere? She raised her face to the silvery summer sky. She tried to hear the words again: Anna, wait for me, but they had gone. She felt cold and the pain in her lungs sharpened. She coughed, wiped away the blood with her sleeve.

‘I can’t wait,’ she murmured.

One foot. Then the other. And the first one again, left right, left right, keep them moving. A brief summer storm had passed, leaving the evening sky pale and drained, much like the snaking trail of women beneath it. The pine trees stood like stiff green sentinels along the track as if in league with the guards.

One foot. Then the other. Don’t let them stop.

The ground was soft with pine needles, the path worn into deep ruts by the daily tramp of hundreds of feet as they marched to and from the Work Zone. Only occasionally did the women catch a glimpse of a lone wolf among the shadows or hear the blood-chilling calls of a hunting pack like ghosts in the forest. That was when the guards’ rifles suddenly became a source of comfort rather than a threat.

It was during the hours that Anna spent walking – or shuffling, if she was being honest – that her mind would skid out of control. It slid from her grasp like a dog slips its collar and runs wild. Without Sofia to laugh at her stories, she no longer had the strength to keep her thoughts together and they raced around in places she didn’t always want to follow them to, colliding with each other.

At first, just separate moments started to skip into her mind, warm and vivid, like riding Papa’s high-stepping black horse whose coat shone like polished metal, and crowing with delight as her childish hands wrapped tight in the coarse black mane. Or her governess, Maria, standing in her second-best silk dress, the one that was the colour of red wine, and telling Papa that Anna couldn’t go out riding on his rounds with him today – he was a doctor – because of a sore throat. Papa’s face had fallen and he’d tickled her under her chin, telling her to get well quickly and calling her his sweet angel. He’d kissed her goodbye, his whiskers all prickly and smelling of fat cigars. Anna had once stolen one from the humidor in his study and shredded it to pieces in secret up in the attic to see if she could find whatever it was that made it smell so wonderful, but all she ended up with was a lap full of crinkly brown dust.

‘You’re smiling,’ Nina muttered beside her, pleased.

‘Tell me, Nina, do you ever think about your past?’

‘Not if I can help it.’

‘So what do you think about?’

Nina’s heavy features spread into a grin. ‘I think about sex. And when I’m too exhausted for that, I think about winning at cards.’

‘Last night I won that grimy piece of mirror off Tasha.’

‘Why on earth do you want a mirror? We all look awful.’

Anna nodded a time or two and watched a bright orange lizard, a yasheritsa, dart out of the path of their marching feet and flash up a tree with an angry flick of its tail.

‘I’m thinking of using it to burn the camp down one sunny day,’ she said.

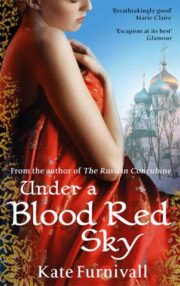

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.