‘Comrades.’

The man who spoke was seated next to Fomenko at the table, a stocky figure with a smooth well-fed face, wiry hair and strangely colourless eyes. He wore a sleek leather jacket, the cost of which even Pyotr could see would have fed Anastasia’s family for a month. This man was the District Party Deputy Chairman, sent by the Raikom, and however much Yuri insisted it was an honour to have him at their meeting, it didn’t feel like that to Pyotr. It felt more like a rebuke.

‘Comrades,’ the man repeated, then paused. He was waiting for absolute quiet.

Fomenko eased back in his chair, instantly yielding control to his superior. The hall fell silent.

‘Comrades, I am proud to be here. With you, my brothers, the workers of Red Arrow kolkhoz. You all know me. I am Deputy Chairman Aleksandr Stirkhov from the Raion Committee. I am a man of the people. I bring a message from our Committee. We praise what you have achieved so far in this difficult year and urge you to greater efforts. The failure of the harvest last autumn was the work of wreckers and saboteurs, funded by foreign powers and their spies who plot to destroy our great new surge forward in technology. Throughout parts of Russia it meant we had to tighten our belts a notch or two-’

‘Or three,’ a man called out from somewhere at the back of the hall.

‘Your own belt doesn’t look so tight, Deputy Stirkhov.’ Another voice.

‘Listen to me, Comrade Deputy, I lost my youngest child to starvation.’ This time Pyotr recognised the voice. It was Anastasia’s mother. He would never forget the morning he’d seen her rocking the dead baby in her arms. Anastasia had missed school that day.

Stirkhov pursed his mouth. ‘Admittedly some shortages have occurred.’

‘It’s a famine,’ Pokrovsky declared at Pyotr’s side. ‘A fucking famine. People dying throughout-’

‘Comrade Deputy Stirkhov is a busy man,’ Fomenko interrupted quickly. ‘He is not here to waste time listening to your observations, Pokrovsky. There is no famine. That is a rumour spread about by the wreckers who have caused shortages through their sabotage of our crops.’

‘That’s a lie.’

Stirkhov rounded on the blacksmith. ‘I remember you. You were a troublemaker when I was here before. Don’t make me note you down as a propagator of Negative Statements, or…’ He left the threat unsaid.

Everyone knew what happened to agitators.

Pokrovsky hunched his massive shoulders as though preparing to swing his hammer on his anvil, but he said nothing that the Comrade Deputy’s ears could pick up. Only Pyotr heard the muttered words lost inside the beard: ‘Fuck you, arse licker.’

‘Blacksmith.’ Stirkhov spoke quietly. He lifted a sheet of paper from the pile on the table. ‘I have here a list of items you made and services you performed in this village which were not strictly for the kolkhoz. Not for the collective farm at all, in fact.’

Pokrovsky ran a hand over his shaven head in a gesture of indifference. ‘So?’

‘So you made a metal trough for Lenko’s chickens, you repaired a stove chimney for Elizaveta Lishnikova, you mended the wheel on Vlasov’s barrow, a pan-handle for Zakarov…’ He raised his reptilian eyes and studied Pokrovsky. ‘Need I go on?’

‘No. What is your point?’

‘My point is whether you were paid for these items?’

‘Not paid exactly. But they thanked me with vegetables or a chicken, yes. And Elizaveta Lishnikova darned my shirts for me. I’m not much good with a needle.’ He held up his thick muscular fingers. There was a gentle titter among the benches. ‘Like I said, not paid exactly.’

‘Without your services, those gifts – and I have a long list of them here – would not have been given to you, so I believe we can class them as payment.’

‘Possibly.’

‘Which makes you a private speculator.’

There was a hush. An intake of breath.

Pyotr wasn’t watching Deputy Stirkhov any more. His eyes were on Chairman Fomenko and he could see the stiffening of sinews in his strong neck. Everyone knew what happened to speculators. Pyotr felt a moment’s panic and glanced swiftly round him.

That was when he saw her, the figure at the back near the door, standing motionless. It was the young woman from the forest, the one with the moonlight hair and her blue eyes were fixed right on him. He felt his throat tighten and he looked away quickly. Why was she here, the fugitive? A wrecker and a saboteur come to make trouble? Should he speak out? If only he possessed Yuri’s absolute certainty of action in a black and white world. He dragged in a deep breath and jumped to his feet again.

‘Comrade Chairman, I have something to say.’

17

Sofia could see what was coming but she didn’t blame the boy when he leapt to his feet. He was trapped. Enticed by the burning zeal. She’d seen it growing in his face each time he turned to glare at the stolid peasants around him, and in the way he leaned further and further away from the dissident blacksmith towards the eager young boy at his side, the one who looked as though he’d stepped out of a propaganda poster.

No, she didn’t blame him. But that didn’t mean she wouldn’t fight him. Quickly she stepped into the aisle between the rows of benches.

‘Comrade Deputy Chairman.’

She spoke out clearly, overriding the boy’s thin voice. Instantly all eyes swung away from him and focused on the newcomer. A murmur trickled round the hall. ‘Who is she? Kto eto? ’

‘State your name, Comrade,’ ordered Stirkhov.

‘My name is Sofia Morozova.’ Her heart was kicking like a mule. ‘I’ve travelled down from Garinzov, near Lesosibirsk in the north, after the death of my aunt. I am the niece by marriage of Rafik Ilyan who cares for your horses.’

Heads turned to Zenia, who was seated next to the tall man with the lion’s mane. She nodded, but kept her eyes fixed firmly on the bench in front and said nothing.

‘What is it you wish to say, Comrade Morozova?’ Stirkhov asked.

He had one of those oily half-smiles on his face, the kind she knew too well, the kind that made her want to spit.

‘Comrade Deputy, I have come to this meeting to offer my labour for the harvest.’

It was Chairman Aleksei Fomenko who responded. ‘We welcome labourers at harvest time when the hours are long and the work is hard. Have you done field work before?’

She stared straight back at him, at the strong lines of his face. His observant grey gaze made her palms sweat.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I’ve done field work.’

‘Where?’

‘On my aunt’s farm.’

‘What kind?’

‘She kept pigs. And sowed oats.’

Enthusiastic voices erupted along the benches.

‘I could use her in my brigade.’

‘We need her in the potato fields!’ a woman shouted out. ‘It’s hard, mind.’

‘She doesn’t look as if she’s up to it, Olga. All straw limbs.’

‘I’m strong,’ Sofia insisted.

A woman in a flowered headscarf and rubber boots reached out from the nearest bench and prodded Sofia’s narrow thigh with a calloused finger. ‘Good muscle.’

‘I’m not a horse,’ Sofia objected, but good-naturedly.

The women laughed. Aleksei Fomenko rapped on the table.

‘Enough! Very well, Sofia Morozova, we will find you work. And I presume Rafik will speak for you.’

‘Yes, my uncle will speak for me.’

‘Have you registered at the kolkhoz office as a resident?’

‘Not yet.’

For the first time he paused. She saw the muscles round his eyes tighten and knew he had started to doubt her. ‘You must do so first thing tomorrow morning.’

‘Of course.’

The boy’s head jerked round to face her, his brown eyes dark with fury as he prepared to speak. That was when she played her trump card.

She smiled straight at the boy and said, ‘I am a qualified tractor driver.’

Pyotr felt his fear of her melt. One moment it was like acid in his throat, burning his flesh, and the next it tasted like honey, all sweet and cloying. He was confused. What had she done to him? She was an Enemy of the People, he was convinced of it. Why else would she be a fugitive in the forest? But when he looked around at the faces he couldn’t understand why they couldn’t see it too. What was she? A vedma? A witch?

‘Pokrovsky,’ he moaned.

The blacksmith glanced down at him. ‘What is it, boy?’

‘I still have something to say.’

‘Just sit still and shut up,’ Pokrovsky growled. His attention was on the stranger.

Pyotr knew that tractor drivers were worth more than the finest black pearls of caviar from the Caspian Sea. The State ran tractor courses at every Machine and Tractor Station throughout the country and a tractor driver was paid more in labour days, sometimes even in cash, but so far no one in the Tivil kolkhoz had succeeded in gaining a place on one of the overcrowded courses. The fugitive had chosen the perfect golden key to open the door into the kolkhoz because a tractor would halve the intensive work of the coming harvest.

‘A tractor driver?’ Fomenko repeated.

‘Yes,’ she answered.

‘You have the MTS certificate?’

‘I have the certificate.’

She was lying, Pyotr was certain she was lying. He could hear the little worms of deceit wriggling against each other as they burrowed into her words.

‘This is excellent news,’ Stirkhov said, ‘otlichnaya novost. The whole village will of course benefit, but…’ He paused, his pale eyes suddenly flatter and harder. ‘But tonight I have come to inform you all of the quotas you are to fulfil with this year’s harvest. The State demands that your quota of contributions be raised.’

A ripple of shock ran through the hall and one woman started to cry in harsh, dry sobs. Moans made a rustling sound like rats in corn stubble. Then came the anger. Pyotr felt it like a wave of hot air, thick on the back of his neck. He was sure the fugitive woman was in some strange way the cause of this dismay, that her presence was drawing disaster to his village.

‘Silence!’ Fomenko rapped on the table. ‘Listen to Comrade Stirkhov.’

‘We’re listening,’ Igor Andreev, a Brigade Leader, said reasonably. His hunting dog whined at his knee. ‘But last December the Politburo ordered the seizing of most of our seed grain and our seed potatoes to feed the towns and the Red Army, so the harvest this season is smaller than a shrew’s balls. We can’t even fulfil the present quotas.’ He stared dully up at Fomenko. ‘Chairman, we’ll be eating rats.’

‘If you work hard,’ Fomenko said quietly, ‘you eat. Stalin has announced the annihilation of begging and pauperism in the countryside. Work hard,’ he repeated, ‘and there will be enough for everyone to eat.’

Stirkhov applauded vigorously. Yuri did the same, and a handful of others clapped with token enthusiasm.

‘Only this week,’ Stirkhov announced, puffing out his chest inside his leather jacket, ‘Stalin is opening the Belomorskiy Kanal. One hundred and twenty million tons of frozen earth were removed by sheer hard labour and now the Baltic Sea is linked to the heartland of Russia. The trade increase in timber alone will bring a flood of prosperity and hard currency to our great Soviet State and its people. And to you as well, brothers of Tivil, so do not talk of failure. See what can be achieved when we work together and follow the vision of our Leader.’

It was Leonid Logvinov who stood up first, the ginger-haired man they still called the Priest, though his church was long gone. Logvinov’s skeletal arm held his wooden crucifix out in front of him, pointing it straight at Stirkhov.

‘God forgive your murdering ways,’ he thundered, ‘and the blaspheming lies of your anti-Christ.’

‘Too far, Priest, you’ve gone too far.’ Stirkhov pounded his fist down on the metal table. But at the same moment the large oak door at the far end slammed open with a crash, rebounding on its hinges, and a wave of cold air swept into the hall. Mikhail Pashin strode into the central aisle, his brown hair windblown, his suit creased.

‘Papa,’ Pyotr cried.

But Mikhail Pashin didn’t hear. ‘Get out of here!’ he shouted. He pointed a finger at the men behind the table on the platform. ‘They’ve tricked you, those two. They’ve kept you cooped up in here while the forces of the Grain Procurement Agency are ransacking your houses. They’re tearing your attics apart, hunting out hidden stores of grain, stripping your larders and stealing your chickens to fulfil their quotas.’

A moan ripped through the benches. Panic forced everyone to their feet.

‘Go home!’ Mikhail shouted above the noise. ‘Before you starve.’

Mikhail Pashin could barely contain his anger. He expelled his breath violently and stepped aside to let the panicked villagers pass. They were pushing and pressing, struggling and shouting, a hundred of them fighting to get through the door as if the blue-capped wolves were actually growling at their heels. It seemed to Mikhail that the people were turning into sheep. Stalin was snipping off their tails yet they didn’t even bleat, despite the fact that ever since the introduction of collectivisation starving peasants had thronged every railway station, clawing their way into the towns and cities. He’d seen them himself, begging in the streets of Kharkov and Moscow, selling their souls for a few kopecks.

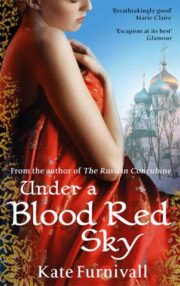

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.