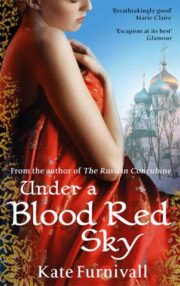

Under a Blood Red Sky

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

For Norman With my love

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Joanne Dickinson and all at Little, Brown for their wonderful enthusiasm and beautiful artwork. I am particularly grateful to Emma Stonex for casting her eagle eye over the manuscript with such expertise.

Special thanks to my agent Teresa Chris for wisely curbing my excesses and for her invaluable insight into the heart of the book.

Thanks also to Alla Sashniluc, not only for providing me with the Russian language but also with a greater understanding of the Russian way of life in a Urals village, and for correcting my blunders.

Finally my love and thanks to Norman for his constant encouragement and advice. It means everything to me.

1

Davinsky Labour Camp, Siberia February 1933

The Zone. That’s what the compound was called.

A double barrier of dense barbed wire encircled it, backed by a high fence and watchtowers that never slept. In Sofia Morozova’s mind it merged with all the other hated lice-ridden camps she’d been in. Transit camps were the worst. They ate up your soul, then spat you out into cattle trucks to move you on to the next one. Etap, it was called, this shifting of prisoners from one camp to another until no friends, no possessions and no self remained. You became nothing. That’s what they wanted.

Work is an Act of Honour, Courage and Heroism. Those words were emblazoned in iron letters a metre high over the gates of Davinsky prison labour camp. Every time Sofia was marched in and out to work in the depths of the taiga forest she read Stalin’s words above her head. Twice a day for the ten years that were her sentence. That would add up to over seven thousand times – that is, if she lived that long, which was unlikely. Would she come to believe that hard labour was an ‘Act of Heroism’ after reading those words seven thousand times? Would she care any more whether she believed it or not?

As she trudged out into the snow in the five o’clock darkness of an Arctic morning with six hundred other prisoners, two abreast in a long silent shuffling crocodile, she spat as she passed under Stalin’s words. The spittle froze before it hit the ground.

‘There’s going to be a white-out,’ Sofia said.

She had an uncanny knack for smelling out the weather half a day before it arrived. It wasn’t something she’d been aware of in the days when she lived near Petrograd, but there the skies were nowhere near as high, nor so alarmingly empty. Out here, where the forests swallowed you whole, it came easily to her. She turned to the young woman sitting at her side.

‘Go on, Anna, you’d better go over and tell the guards to get the ropes out.’

‘A good excuse for me to warm my hands on their fire, anyway.’ Anna smiled. She was a fragile figure, always quick to find a smile, but the shadows under her blue eyes had grown so dark they looked bruised, as though she’d been in a fight.

Sofia was more worried about her friend than she was willing to admit, even to herself. Just watching Anna stamping her feet to keep the blood flowing made her anxious.

‘Make sure the brainless bastards take note of it,’ grimaced Nina, a wide-hipped Ukrainian who knew how to swing a sledgehammer better than any of them. ‘I don’t want our brigade to lose any of you in the white-out. We need every single pair of hands if we’re ever going to get this blasted road built.’

When visibility dropped to absolute zero in blizzard conditions, the prisoners were roped together on the long trek back to camp. Not to stop them escaping, but to prevent them blundering out of line and freezing to death in the snow.

‘Fuck the ropes,’ snorted Tasha, the woman on the other side of Sofia. Tasha tucked her greasy dark hair back under her headscarf. She had small narrow features and a prim mouth that was surprisingly adept at swearing. ‘If they’ve got any bloody sense, we’ll finish early today and get back to the stinking huts ahead of it.’

‘That would be better for you, Anna,’ Sofia nodded. ‘A shorter day. You could rest.’

‘Don’t worry about me.’

‘But I do worry.’

‘No, I’m doing well today. I’ll soon be catching up with your work rate, Nina. You’d better watch out.’

Anna gave a mischievous smile to the three other women and they laughed outright, but Sofia noticed that her friend didn’t miss the quick glance that passed between them. Anna struggled against another spasm of coughing and sipped her midday chai to soothe her raw throat. Not that the drink deserved to be called tea. It was a bitter brew made from pine needles and moss that was said to fight scurvy. Whether that was true or just a rumour spread around to make them drink the brown muck was uncertain, but it fooled the stomach into thinking it was being fed and that was all they cared about.

The four women were seated on a felled pine tree, huddled together for warmth, kicking bald patches in the snow with their lapti, boots shaped from soft birch bark. They were making the most of their half-hour midday break from perpetual labour. Sofia tipped her head back to ease the ache in her shoulders and stared up at the blank white sky – today lying like a lid over them, shutting them in, pressing them down, stealing their freedom away. She felt a familiar ball of anger burn in her chest. This was no life. Not even fit for an animal. But anger was not the answer, because all it did was drain the few pathetic scraps of energy she possessed from her veins. She knew that. She’d struggled to rid herself of it but it wouldn’t go away. It trailed in her footsteps like a sick dog.

All around, as far as the eye could see and the mind could imagine, stretched dense forests of pine trees, great seas of them that swept in endless waves across the whole of northern Russia, packed tight under snow – and through it all they were attempting to carve a road. It was like trying to dig a coal mine with a teaspoon. Dear God, but road-building was wretched. Brutal at the best of times, but with inadequate tools and temperatures of twenty or even thirty degrees below freezing it became a living nightmare. Your shovels cracked, your hands turned black, your breath froze in your lungs.

‘Davay! Hurry! Back to work!’

The guards crowded round the brazier and shouted orders, but they didn’t leave their circle of precious warmth. Along the length of the arrow-straight scar that sliced through the trees to make space for the new road, hunched bodies pulled their padded coats and ragged gloves over any patch of exposed skin. A collective sigh of resignation rose like smoke in the air as the brigades of women took up their hammers and spades once more.

Anna was the first on her feet, eager to prove she could meet the required norm, the work quota for each day. ‘Come on, you lazy…’ she muttered to herself.

But she didn’t finish the sentence. She swayed, her blue eyes glazed, and she would have fallen if she hadn’t been clutching her shovel. Sofia reached her first and held her safe, the frail body starting to shake as coughs raked her lungs. She jammed a rag over Anna’s mouth.

‘She won’t last,’ Tasha whispered. ‘Her fucking lungs are-’

‘Ssh.’ Sofia frowned at her.

Nina patted Anna’s shoulder and said nothing. Sofia walked Anna back to her patch of the road, helped her scramble up on to its raised surface and gently placed the shovel in her hand. Not once had Anna come even close to meeting the norm in the last month and that meant less food each day in her ration. Sofia shifted a few shovels of rock for her.

‘Thanks,’ Anna said and wiped her mouth. ‘Get on with your own work.’ She managed a convincing smile. ‘We’ll be home early today. Before the white-out hits.’

Sofia stared at her with amazement. Home. How could she bear to call that place home?

‘I’ll be fine now,’ Anna assured her.

You’re not fine, Sofia wanted to shout, and you’re not going to be fine.

Instead she gazed hard into her friend’s sunken eyes and what she saw there made her chest tighten. Oh, Anna. A frail wisp of a thing, just twenty-eight years old. Too soon to die, much too soon. And that moment, on an ice-bound patch of rock in an empty Siberian wilderness, was when Sofia made the decision. I swear to God, Anna, I’ll get you out of here. If it kills me.

2

The white-out came just as Sofia said it would. But this time the guards paid heed to her warning, and before it hit they roped together the grey crocodile of ragged figures and set off on the long mindless trudge back to camp.

The track threaded its way through unremitting taiga forest, so dark it was like night, the slender columns of pine trees standing like Stalin’s sentinels overseeing the march. The breath of hundreds of women created a strange, disturbing sound in the silence, while their feet shuffled and stumbled over snow-caked ruts.

Sofia hated the forest. It was odd because she had spent most of her life on a farm and was used to rural living, whereas Anna, who loved the forest and declared it magical, had been brought up in cities. But maybe that was why. Sofia knew too well what a forest was capable of, she could feel it breathing down her neck like a huge unwelcome presence, so that when sudden soft sounds escaped from the trees as layers of snow slid from the branches to the forest floor, it made her shiver. It was as though the forest were sighing.

The wind picked up, stealing the last remnants of heat from their bodies. As the prisoners made their way through the trees, Sofia and Anna ducked their faces out of the icy blast, pulling their scarves tighter round their heads. They pushed one exhausted foot in front of the other and huddled their bodies close to each other. This was an attempt to share their remaining wisps of warmth, but it was also something else, something more important to both of them. More important even than heat.

They talked to each other. Not just the usual moans about aching backs or broken spades or which brigade was falling behind on its norm, but real words that wove real pictures. The harsh scenes that made up the daily, brutal existence of Davinsky Camp were difficult to escape, even in your head they clamoured at you. Their grip on the mind, as well as on the body, was so intractable that no other thoughts could squeeze their way in.

Early on, Sofia had worked out that in a labour camp you exist from minute to minute, from mouthful to mouthful. You divide every piece of time into tiny portions and you tell yourself you can survive just this small portion. That’s how you get through a day. No past, no future, just this moment. Sofia had been certain that it was the only way to survive here, a slow and painful starvation of the soul.

But Anna had other ideas. She had broken all Sofia’s self-imposed rules and made each day bearable. With words. Each morning on the two-hour trek out to the Work Zone and each evening on the weary trudge back to the camp, they put their heads close and created pictures, each word a colourful stitch in the tapestry, until the delicately crafted scenes were all their eyes could see. The guards, the rifles, the dank forest and the unrelenting savagery of the place faded, like dreams fade, so that they were left with no more than faint snatches of something dimly remembered.

Anna was best at it. She could make the words dance. She would tell her stories and then laugh with pure pleasure. And the sound of it was so rare and so unfettered that other heads would turn and whimper with envy. The stories were all about Anna’s childhood in Petrograd before the Revolution, and day by day, month by month, year by year, Sofia felt the words and the stories build up inside her own bones. They packed tight and dense in there where the marrow was long gone, and kept her limbs firm and solid as she swung an axe or dug a ditch.

But now things had changed. As the snow began to fall and whiten the shoulders of the prisoners in front, Sofia turned away from them and faced Anna. It had taken her a long time to get used to the howling of a Siberian wind but now she could switch it off in her ears, along with the growls of the guard dogs and the sobs of the girl behind.

‘Anna,’ she urged, holding on to the rope that bound them together, ‘tell me about Vasily again.’

Anna smiled, she couldn’t help it. Just the mention of the name Vasily turned a light on inside her, however wet or tired or sick she was. Vasily Dyuzheyev – he was Anna’s childhood friend in Petrograd, two years older but her companion in every waking thought and in many of her night-time dreams. He was the son of Svetlana and Grigori Dyuzheyev, aristocratic friends of Anna’s father, and right now Sofia needed to know everything about him. Everything. And not just for pleasure this time – though she didn’t like to admit, even to herself, how much pleasure Anna’s talking of Vasily gave her – for now it was serious.

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.