‘Sofia.’

It was Rafik.

‘What are you doing out here?’ His voice was faint.

‘Searching for Pyotr Pashin. Have you seen the boy?’

He shook his head. It was that movement, slow and heavy, that made Sofia peer through the night’s drizzle more closely. What she saw shocked her. His black eyes were dull, the colour of old coal dust. Sweat, not rain, glimmered on his forehead.

‘Rafik, are you wounded?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sick?’

‘No.’ It was little more than a breath.

‘Let me take you home.’ She lifted his hand in hers. It was ice cold. ‘You need-’

The crash of a rifle butt came from within the house closest to them. He withdrew his hand.

‘Thank you, Sofia, but I have work to do.’

He headed off with an uneven gait towards a group of approaching uniforms and her confidence in him was shaken. He was going to get himself killed if he interfered.

Pyotr was running up to the stables when Sofia stepped out of the darkness and caught him. Her fingers fastened round his wrist and he was astonished at the strength in them. One look at her face and it was clear she wasn’t going to let him go this time.

‘Privet,’ she said with no hint of annoyance that he’d run off before. ‘Hello again.’

‘I was just going to check on Zvezda,’ he said quickly. ‘Papa’s horse. To make sure he wasn’t taken by the troops.’

She paused, considered the idea, then nodded as if satisfied and led him up the rest of the narrow track to where the stable spread out round a courtyard. Once inside the stables she released his wrist and lit a kerosene lamp on the wall in a leisurely way, as if they’d just come up for a cosy chat instead of to escape from the soldiers. Pyotr wouldn’t admit it but he had been frightened by the savagery of what was tearing his village apart tonight. Her blue eyes followed his every move as he refilled Zvezda’s water bucket, the horse’s warm oaty breath on his neck, and for some reason her gaze made him feel clumsy.

‘Zvezda is growing restless,’ she said, lifting a hand to scratch the animal’s nose.

Pyotr wrapped an arm round the muscular neck and embedded his fingers in its thick black mane. The other horses were whinnying uneasily from their stalls and it dawned on Pyotr that something wasn’t right, but he couldn’t work out what. It must be because of Sofia, he told himself. But when he slid his eyes towards her, she didn’t look threatening at all, just soft and golden in the yellow lamplight. He was just beginning to wonder whether he’d got her all wrong when she all of a sudden put a finger to her lips, the way she did in the forest that time.

‘Listen,’ she whispered.

Pyotr listened. At first he heard nothing but the restless noises of the horses and the wind chasing over the corrugated iron roof. He listened harder and underneath those he caught another sound, a dull roar that set his teeth on edge.

‘What’s that?’ he demanded.

‘What do you think it is?’

‘It sounds like-’

‘Pyotr!’ The priest burst into the stables and instantly checked the dozen stalls to ensure the horses were not panicked. ‘Pyotr,’ he groaned, ‘it’s the barn, the one where the wagons are kept. It’s on fire!’

His windblown hair leapt and darted about him as if the fire were ablaze on his shoulders. His angular frame shuddered disjointedly while he moved from one horse to the other, patting their necks and soothing their twitching hides. He was wrapped in a horse blanket that was more holes than material.

‘I am a vengeful God, saith the Lord.’ His wild green eyes swung round to face Pyotr. ‘I tell you, this is the Hand of God at work. His punishment for the evil here tonight.’

His long finger started to uncurl in Pyotr’s direction. For one horrible moment Pyotr thought it was going to skewer right into the bones of his chest, but the slight figure of Sofia brushed it aside as she hurried to the door of the stable. She looked out into the night and called out. ‘Come here, Pyotr.’

Pyotr rushed to her side and gasped. The whole of the night sky was on fire. Flames scorching the stars. It sent Pyotr’s mind spinning. Once before he’d seen an inferno like this and it had changed his life. He made a move to dash towards it but Sofia’s hand descended firmly on his shoulder.

‘You’re needed here, Pyotr,’ she said in a steady voice. ‘To help calm the horses.’

Pyotr saw the priest and the fugitive exchange a look.

‘She’s right,’ Priest Logvinov said. He flung out both arms in appeal. ‘I’ll need as much help as I can get with the horses tonight. Right now they have the stink of smoke in their nostrils.’

‘But I want to find Papa.’

‘No, Pyotr, stay here,’ she ordered, but her eyes were on the flames and a crease of worry was deepening on her forehead. ‘I’ll make sure your papa is safe.’ Without another word she hurried away into the night.

21

Gigantic flames were ripping great holes in the belly of the night sky. Spitting and writhing, they leapt twenty metres into the air, so that even down at the river’s edge Mikhail Pashin could feel the sting of sparks in his eyes, the smoke in his lungs. He was on his knees, his trousers wet and his knuckles skinned, crouched over the water pump on the riverbank, struggling in the darkness to bring it to life. It had so far resisted all his coaxing and cursing. In frustration he clouted his heftiest wrench against the pump’s metal casing and instantly the engine spluttered, coughed, then racketed into action, sending gallons of river water racing up the rubber hose.

‘The scientific approach, I see,’ a voice said out of the darkness.

In the gloom he made out nothing at first, just the creeping shadows etched against the red glow of the sky, but then he saw a pale oval. A face close by.

‘It’s Sofia,’ she said.

‘I thought you were at my house, you and Pyotr.’

‘Don’t worry. Your son is safe in the stables with Zvezda and the priest.’

‘Good. They’ll be out of harm’s way up there.’

She moved closer, and as she did so one side of her face was painted golden by the flames, highlighting the fine bones of her cheek, the other side an impenetrable mask in the blackness. She stood over him, looking down, and for a brief second he was startled because he thought she was going to touch his hair, but instead she crouched down on her haunches on the opposite side of the pump. Their faces were on a level and he could see the firelight reflected off the glassy surface of the river and into her eyes. He was surprised by the humour in them on a night like this. She looked as if the fire were burning inside her.

‘The whole village is helping,’ she said. Her words merged with the clanking of the engine.

‘Yes, in an emergency the kolkhoz knows how to work together.’ He glanced over his shoulder to the spot where a long line of men and women, clutching buckets, snaked up from the river all the way to the burning barn. Each face was grim and determined.

‘A human pipeline,’ Sofia muttered.

‘Who the hell did this? Who would wish to burn down our barn?’

‘Mikhail, look who’s in the line.’

‘In the line? The villagers, you mean?’

‘And?’

‘The troops helping them.’

‘Exactly.’

‘What about them?’

He was running a hand over the engine to steady it, enjoying its heartbeat. The feel of machinery under his fingers always strengthened him in some strange indefinable way that he didn’t understand. Sofia’s hand reached out and lightly brushed his own.

‘Look at them,’ she said urgently.

He frowned. What did she mean? He studied the troops striving hard in the line to prevent the fire from spreading to a second barn. Their caps were smut-stained, their skin streaked with sweat, some wore kerchiefs tied over the lower half of their face to protect their lungs, some cursing and shouting for more speed, uniformed men all fighting side by side with the villagers.

‘Look hard,’ she whispered.

He looked.

Nothing. He could see nothing. What on earth was she talking about? Just the blackness and the clawing flames. The effort of all those workers. Then suddenly it dawned. His pulse raced as he realised this was the moment when the troops’ attention was totally diverted from the grain. Why the hell hadn’t he seen it himself? He leapt to his feet, abandoning the water pump to its own steady rhythm, and raced up through the drooping willows towards the centre of the village. Sofia matched him stride for stride.

‘Wait here,’ Mikhail ordered. ‘And make no sound.’

The small group of villagers nodded, huddled silent and invisible at the side of the blacksmith’s forge where the night wrapped them in heavy shadows. Four women, one of them sick, and two old men. Their backs didn’t look strong enough to hoist the sacks but they were all Mikhail could find inside the houses. Everyone else was up at the fire, so they’d have to do. Plus Sofia, of course. Just as he was about to edge away, she leaned close to him, her breath warm on his ear as she whispered, ‘Take care. I promised Pyotr I’d make sure you stayed safe.’

He couldn’t see her eyes, so he touched her hand in reassurance. It felt strong and swept away his doubts about the handling of the sacks.

‘I’ll be back,’ he promised and walked out into the main street.

It was dark and deserted now, except for the truck. Beside the truck stood a man with a long coat flapping at his ankles and a Mauser pistol in his fist. Mikhail glanced around but there were no other troops in sight. This one was leaning against the tailgate, cigarette in hand, guarding the sacks on the flatbed and waiting casually for his comrades to return, but there was nothing relaxed or casual about his face. His head turned with every moment that passed, eyes behind his thick spectacles scanning every point of access. He was no fool. He recognised the danger.

‘Oy moroz, moroz, nye moroz menya, Nye moroz menya, moevo kon,’ Mikhail began singing, loud and boisterous.

The words slipped over each other in his mouth. He aimed himself in the general direction of the truck but his feet wove from one side of the road to the other, stumbling and tripping, only just correcting themselves in time. He threw back his head and laughed.

‘Hey, comrade, my friend, how about a drink?’ His words came out slurred and he brandished a bottle of vodka he’d snatched from the smithy, at the same time looking around the dark street in a bewildered manner. ‘Where’sh everyone?’

The man pushed himself off the truck, threw the cigarette in the dirt and ground his heel on it. He regarded Mikhail with caution.

‘Who are you?’

‘I’m your friend, your good friend,’ Mikhail grinned lop-sidedly and thrust out the bottle. ‘Here, have a drink.’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’ Mikhail upended the bottle and took a slug of the vodka himself. He felt it burn the knots in his stomach. ‘Is good stuff,’ he mumbled.

‘You’re drunk, you stupid oaf.’

‘Drunk but happy. You don’t look happy, tovarishch.’

‘Neither would you if you had to deal with such-’

‘Here.’ Mikhail thrust the bottle at the man again. ‘Some left for you. You could be out here all night.’

The fire reflected in the man’s spectacles. His hesitation betrayed him, so Mikhail seized the hand that had discarded the cigarette and wrapped it round the bottle. ‘Put fire in your belly.’ He rocked on his heels with laughter. ‘Fire in your belly instead of in our barn.’

The man’s mouth slackened. He almost smiled.

‘Let’s have it.’ He took a mouthful. Smacked his lips.

‘Good?’

‘It’s cat’s piss. It’s no wonder you peasants are mindless. This homemade brew rots your brains.’

‘Come with me, Comrade Officer, and I will show you…’ Mikhail lowered his voice in conspiratorial style, ‘the real stuff. The good stuff.’

‘Where?’ Another swig.

‘In my house. It’s just over-’

‘No. Piss off. I’m guarding this truck.’

Mikhail yawned, stretched, scratched himself and stumbled on his feet.

‘Come, Comrade Officer, there’s no one here. Your sacks are safe.’ He draped an arm across the man’s shoulders, could smell cheap tobacco on his breath. ‘Come, friend, come and taste the good stuff.’

The man was drunker than a mule. His eyes turned pink and his tongue seemed too large for his mouth, so that the words slid off it into his glass. But when Mikhail yanked him to his feet after an hour of pouring his best vodka down the bastard’s throat, it came as a surprise at the door to find he still had a few wits clinging to him.

‘You come too,’ the man said, his head lolling on his thick neck.

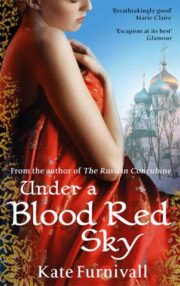

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.