‘That must have been exciting.’

A pause. Two dragonflies chased alongside for an iridescent second before darting back to the river.

‘Yes.’ That was all he said.

‘Very different from a clothing factory out here in the middle of nowhere, that’s certain,’ she said lightly. ‘Sewing machines aren’t much good at flying.’

He laughed once more but this time it sounded empty. ‘Oh yes, I’m well and truly earthbound these days.’

It wasn’t hard to picture him soaring through the clouds, eyes bright with joy, up in the freedom of the blue sky. But she didn’t ask the obvious question, made no attempt to search out the why or the how. Instead she laid her cheek against his shoulder. They rode like that in silence and she could feel the thread between them spinning tighter, drawing them together.

After several minutes, as though he could hear her thoughts, he said flatly, ‘I was dismissed. I wrote a letter. To a friend in Leningrad. In it I complained that some of the equipment was agonisingly slow in arriving at the N22 factory because of incompetence, despite the fact that Stalin himself claimed to be committed to expanding the aircraft industry as a major priority.’

‘Foolish,’ she murmured and gently tapped his head. His hair felt soft.

‘Foolish is right.’ He leaned back a fraction in the saddle, so that his shoulder pressed harder against her cheek. ‘I should have realised all employees in such a sensitive project would have their letters monitored. Bloody idiot. It was only because Andrei Tupolev himself intervened for me that I wasn’t sent to one of the Siberian labour camps. Instead I was exiled out here in, as you so aptly put it, the middle of nowhere. But I’m an engineer, Sofia, not a bloody clothes merchant.’

‘You were lucky.’ Sofia sat up straight once more. ‘You must be careful, Mikhail.’

‘I admit I’ve had a few run-ins with Stirkhov and his Raion Committee already. I’m an engineer, and since all the big public show trials of the engineers he doesn’t trust me and is always wanting to interfere.’

‘What show trials?’

It slipped out. She wanted to cram the words back inside her mouth.

‘Sofia, you must have heard of them, everyone has. The trials of the industrial engineers. The first one was the Shakhty trial in 1928. Remember it? Fifty technicians from the coal industry. The poor bastards were accused by Prosecutor Krylenko of cutting production and of being in the pay of foreign powers. Of taking food out of the mouths of the hungry masses and of treachery to the Motherland.’

She could feel his back growing rigid.

‘Everyone clamoured for the deaths of these men, who were forced into confessing incredible and absurd crimes, slavish and servile in court. They betrayed the whole engineering industry, humiliated us. Endangered us.’ He paused suddenly and she wondered where his mind had veered to, but she soon found out.

It was in a totally different sort of voice that he said, ‘You’d have to be blind and deaf and dumb not to know of the trials. They were a huge spectacle. Used by Stalin as propaganda in every newspaper and radio broadcast, in newsreels and on billboards. We were completely bombarded for months.’ Abruptly he stopped speaking.

‘I was ill,’ she lied.

‘Blind and deaf,’ he murmured, ‘… or not in a position to read a newspaper.’

‘I was ill,’ she repeated.

‘You can read, can’t you?’

‘Yes. But I had… typhoid fever. I was sick for months and read no newspapers.’

‘I see.’

He said it so coldly she shivered. They rode the rest of the way into town in silence.

The town of Dagorsk seemed to press in on Sofia as she walked its pavements alongside Mikhail. The buildings were tombstone-grey and crowded on top of each other, either old and dilapidated or new and scruffy. There was beauty there in some of the fine old houses but it was hidden under layers of dirt and neglect. Doors and windows remained unpainted because paint was scarcer than white crows these days, and the pavements were broken and treacherous. It used to be a quiet market town tucked away on the eastern slopes of the Ural Mountains, but since Stalin had vowed in 1929 to civilise the backward peasants of Russia and to liquidate as a class the kulaks, the wealthy farmers, Dagorsk had been jolted suddenly into the twentieth century. The austerities of Communism cast a shadow over the town: shop windows were rendered empty black holes and goods had become impossible to obtain.

Factories had sprung up on the edge of the town and were turning the air grey with the soot from their chimneys. The people had changed too. Gone were the easy-going exchanges, the reassurance of a familiar face, as new forbidding apartment blocks and tenements filled up with strangers looking for work. Or, even worse, strangers who had been exiled to this remote region because of crimes committed against the State. Dagorsk was crawling with people avoiding each other’s eyes, and with cars and carts avoiding each other’s axles, as the web of suspicion and paranoia spread through the streets. Sofia felt uneasy.

‘It’s always frantic here,’ Mikhail said as they walked quickly past a squat onion-domed church that lay in ruins. ‘It’s why I choose to live out in the peace and quiet of Tivil, though I’m not so sure my son agrees with me. He’s still young. I think he’d prefer the energy of Dagorsk.’

‘No, I get the feeling he likes the countryside. Especially the forest.’

‘Maybe. He certainly enjoys working in Pokrovsky’s smithy in his free time.’ He sounded pleased. ‘And you?’

‘I’m not good with crowds.’

‘So I noticed.’

He smiled at her and she realised that since leaving the horse in the haulage yard and setting off on foot through the maze of streets, through the press of other people’s bodies, she had gravitated nearer and nearer to Mikhail. He had slowed his stride to her pace and brushed against her, aware of her unease. She could feel the weight of his arm beside her, the nearness of his shoulder. Did the smile mean he had forgiven her the lie?

‘My spinster aunt didn’t like crowds either, she preferred pigs,’ Sofia said, because she wanted another of his smiles.

‘Pigs?’

‘Yes. One gigantic sow in particular, called Koroleva. She used to walk the pig up the mountain twice a year, regular as clockwork. It was to meet up with a farmer and his boar from the next valley who walked up from the other side of the mountain, rain, wind or shine. They’d spend a few days up there away from all the crowds while the pigs enjoyed more than just the pine nuts, and then they came down again until the next time.’

‘I bet they produced strong litters after all that walking.’

‘Yes, good sturdy ones. But as a child it took me years to realise that Koroleva wasn’t the only one getting serviced on the mountain. Regular as clockwork.’

He threw back his head and laughed. ‘You’re making it up.’

‘No, I’m not.’ She flushed slightly.

They stood still for a moment, smiling into each other’s eyes. She loved him for his laugh in a world where people had forgotten how to make that sound. He threaded her arm through his and guided her along the twists and turns up to the central square, steering her past the clutching hands of the beggars that pulled at her clothes like thorns. In time they came to a halt at a broad crossroads where the radio loudspeakers were blaring out into the street. It was one of Stalin’s speeches read by Yuri Levitan, hour after hour of it. Oblivious to the long queue of silent women outside the bakery, Mikhail turned Sofia to face him, holding her shoulders. His grey eyes were bright with curiosity and his mouth curved in an echo of his earlier laughter.

‘Sofia, what exactly are you doing here?’

‘I’ve come to visit the apteka, the chemist on Kirov Street. For Rafik.’

She knew it wasn’t what he meant. He meant to know what was she doing in Tivil, but she wasn’t ready for that. Not yet. It was too soon to tell him about Anna, too soon to be certain he wouldn’t report her as a fugitive from one of the forced labour camps. If he did, all hope of saving Anna would be lost. He watched her intently, then his fingers took hold of her hand, turned it over and placed a fifty rouble note from his pocket on its palm. One by one he wrapped her fingers over the note.

‘I must leave you now, Sofia. Go buy yourself some food.’ Gently he touched a fingertip to her cheek. ‘Put some flesh on your bones.’

His hand was so male. She noticed that about it. She’d been cut off from maleness for so long. His palm was broad and his fingernails short and hard. She took a deep breath. Now was the time to ask.

‘Mikhail, will you give me a job?’

‘Oh Sofia, I-’

‘I’ll do anything,’ she rushed on. ‘Sweep floors, oil machines, type invoices… and I can sew too, if-’

A passing motorcycle roared up the street, smothering the life out of her words, but not before she had seen despair leap into Mikhail’s face.

‘I’m sorry, Sofia. There are queues of people at my factory gate every day, nothing but pathetic bundles of rags and rib bones, people who are desperate.’

‘I’m desperate, Mikhail.’

He frowned. His gaze moved over her body in a way that made her blush. ‘You’re not starving,’ he said quietly.

‘No. That’s true. Thanks to Rafik I’m not starving. But-’

‘And you’ll have work on the farm.’ He smiled again. ‘I hear you’re the famous tractor driver who will lighten the load of the harvesters this autumn.’

‘Work on the kolkhoz is no use to me,’ she said impatiently. ‘I’ll do all I can for them and it’ll put a roof over my head and food in my stomach but it won’t provide me with what I need, which is-’ She stopped.

‘Money?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m sorry, Sofia. I can’t.’

‘Just one or two days a week?’

‘You don’t seem to understand,’ he said bleakly. ‘I can’t give work to everyone. I have to choose. Choose between who earns enough money to eat that day and who doesn’t.’ His eyes grew as dark and flat as the pavement under their feet. ‘I’m forced to decide who lives and who dies. It’s…’ he looked away at the road ahead, ‘my penance.’

‘Please,’ she whispered, ashamed to beg. Their eyes held each other. ‘It is life or death, Mikhail. If it weren’t, I wouldn’t ask. I need money.’

He stared at her a moment longer and she could see herself through his eyes. She was filled with disgust at what must look like her greed. She stepped away from him.

‘Think about it anyway,’ she said with a try at lightness and a smile that cost her dear. ‘Thanks for taking me on your horse. And for this.’ She held up the note and ducked out into the road, dodging a handcart piled high with old newspapers tied together with wire. Her disappointment was so solid it almost choked her. She’d spoiled everything.

When she reached the other side of the road she turned to wave and saw that Mikhail was still standing exactly where she’d left him on the pavement, staring after her, but he was no longer alone. Beside him stood a slight female figure in a light summer dress. The dress had a patch near the hem but otherwise looked fresh and clean, unlike Sofia’s own shabby skirt. With a shock she recognised Lilya Dimentieva, the same woman she’d seen so intimately entwined with Mikhail last night, the one who’d come to the house to whisper with Zenia. The one with the child, Misha. That one.

She was smiling up into his face with tempting brown eyes and, as Sofia watched, Lilya slipped her arm through Mikhail’s, rubbing her shoulder against him like a cat. Together they set off down the street.

Sofia was furious. She wanted to snap something brittle between her fingers. Something like Lilya Dimentieva’s thin neck. She was furious with Mikhail and knew she had no right to be. He wasn’t hers.

She hurried down Ulitsa Gorkova with long unforgiving strides, indifferent now to the crowds milling round her, as though she could outpace her rage at that possessive little movement of Lilya’s. But she couldn’t. It burned as fiercely as hell fire, melting her from the inside.

As Sofia emerged from the gloomy apteka into the bright sunlight on Kirov Street, she clutched Rafik’s paper package in her hand and headed down towards the factories hunched together on the river bank. Here the River Tiva had widened out to a busy thoroughfare where long black barges nudged up alongside the warehouses and men were shouting and hurling ropes. Sofia looked at its oily restless surface and wondered how far a small rowboat might travel on it. It was something to consider.

She had no trouble finding the Levitsky factory. It was an ugly red-brick building that rose three storeys up from the muddy bank, with derricks jutting out over the river at the rear, and at the front a set of studded pine doors large enough to swallow carts whole. Attached to it at one side was a modern concrete extension with rows of wide windows that must flood the place with sunshine.

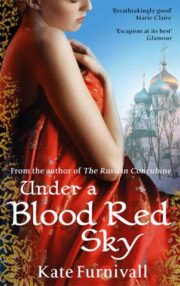

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.