Why on earth would he need notes for a lover?

With a small sense of shock she became aware of the dog. It was stretched out on the floor, licking dirt from one paw with long sweeps of its tongue, but abruptly it stopped. Its head lifted, eyes and ears alert. It gazed at the closed door and, making no sound, it raised its lips to show its teeth in a silent snarl. Sofia didn’t know what its quick ears had picked up but she wasn’t going to hang around to find out. She pushed herself away from the hut and raced away back down the track to Tivil.

32

Davinsky Camp July 1933

After the business with the cat, Anna lay awake, propped upright against the damp wood of the hut wall to ease her breathing. Beside her on the bed board lay a squat, nervy woman, who spent every waking hour angry and resentful to the point where she could barely sleep at night. She lay on her side staring wide-eyed at the degraded world inside the hut, hating it with a passion that was killing her.

Anna didn’t want to be like that. She didn’t want to hate until that was all that was left inside her. She’d seen it again and again, the way prisoners died from hate, and she tried to spit its insidious bitter taste from her mouth, but sometimes it was hard. Especially without Sofia to make her laugh. She missed Sofia.

Ever since the cat she had missed Sofia even more. Sofia would have known how to rid her head of the images that swarmed inside it. It was that stupid cat’s fault, scratching Tasha’s hand like that. Because now that Anna had let that terrible day back into her head, it settled there, gnawing at her and refusing to go away. Even as she hacked away at the branches all day in the forest, trying to block her mind with thoughts of the futile arrogance of the guards or the fragrance of the pine sap, the memory sank its powerful teeth into her and kept dragging her back to Petrograd and that cold winter of 1917.

She had became a shadow after her father died in the snow, no longer a person, just a twelve-year-old shadow inside a cramped and stuffy apartment that belonged to Maria’s brother, Sergei, and his wife, Irina. Her skin turned grey, she rarely spoke and only picked at the barest crumbs of food. But she learned to call Maria Mama and she wore a plain brown peasant dress without complaint and ate black bread instead of white. At night she shared Maria’s narrow cot and spent the hours of darkness lying obediently on the sour-smelling mattress. She never seemed to close her eyes. They had changed from their bright cornflower blue to a dull muddy colour that matched the winter gloom of the River Neva. Yet still she wouldn’t cry.

‘It’s not natural,’ Irina said in a low voice. ‘Her father has just died. Why doesn’t she cry?’

‘Give her time,’ Maria murmured to her sister-in-law as she ran a hand over the silky blonde head. ‘She’s still too shocked.’

‘A shock is what that girl needs,’ Irina said and mimed a quick little slap with her hand. ‘It’s like having a corpse in the house.’ She shivered dramatically. ‘The child gives Sergei and me the creeps, she does. How you can sleep with her in your bed, I don’t know.’

‘Irina, please. She’s silent but she’s not deaf.’

‘No, you’re not deaf are you, Anna? Just wilful. Well, child, it’s time to snap out of it and give your poor Maria a chance to get on with her own life. She’s starting a new job tomorrow and can’t spend time fretting about you.’

Anna’s muddy eyes turned to Maria, panic fierce in them. ‘Can’t I come with you?’ Her voice was barely a whisper. ‘I can work too.’

‘No, my love.’ Maria kissed her forehead in the dark. ‘I’m working in a factory, putting washers on taps. It’ll be noisy and dirty and unimaginably boring. You’ll enjoy it much more here with little Sasha and Aunt Irina.’

‘You might die tomorrow. Among the taps.’

Maria put an arm round Anna and rocked her gently. ‘Neither of us will die, I swear to you. You must wait patiently for me to return.’

A soft moan escaped from the back of Anna’s throat.

Anna spent the day at the window. She kissed Maria goodbye at the door of the first-floor apartment and then ran to the window to wave to her all the way down the street, but the moment Maria was out of sight, a suffocating blackness swarmed into her mind. It stopped her breathing. Air wouldn’t go into her lungs and sometimes she had to beat her ribs with her fists, pushing her chest in and out to make air suck in and blow out. Irina clipped her round the ear for doing it, saying she was being silly and mustn’t scare Sasha, who was watching Anna from his colourful rag-rug with a big grin on his face. His ears, which stuck out like wings, listened to every sound she made.

Anna counted. She counted her fingers, she counted the number of blue flowers on the wallpaper, the spots on Sasha’s chin, the chimneys on the roofs, the tiles on the house opposite, the people in the street, the pigeons in the gutter. She even tried to count the snowflakes when they fell from a colourless sky but that was too hard. Only when the sky grew dark and Maria came home, only then did Anna believe Maria was still alive.

They came for Maria in the middle of the night. They barely gave her time to pull a dress on over her nightgown, but she was quick to push Anna firmly against the wall.

‘Stay there,’ she told her fiercely.

So Anna stayed there. But when the big man in the arrogant boots and the long overcoat patted her on the shoulder and told her not to fret, she wanted to bite him. To sink her teeth into his wrist where the ugly blue veins bulged above his black leather gloves and make his blood flow on to the floorboards. Maria said little, but when she bent to pull her felt valenki on her feet, Anna could see the white skin on the back of her neck twitching as if spiders were crawling over it.

It was Sergei who put up the fight.

‘What do you want with my sister?’ he demanded. ‘She’s a good worker. She’s done nothing. We are a loyal Bolshevik family. I marched on the Winter Palace with the best of them. Look,’ he yanked open the front of his nightwear to reveal a livid scar across his chest, ‘I am proud to bear the mark of a sabre.’

‘I salute you, comrade,’ said the man in the overcoat. His face was shrewd. ‘But it’s not you we want to question, it’s her.’

‘But she’s my sister and would never-’

‘Enough, comrade.’ He held up his hand for silence, a man accustomed to being obeyed. ‘Take her outside,’ he ordered two of his soldiers.

‘Maria.’ It was Irina who darted forward. ‘Take this.’ She thrust her own warmest fur hat on to her sister-in-law’s head, a piece of cheese into her hand, and gave her a quick peck on the cheek. ‘Just in case,’ she whispered.

Maria blinked but couldn’t speak. Her face looked frozen.

Just in case? Of what? Anna wanted to scream. What would they do to her, these huge soldiers whose shoulders packed the small room with their hard muscles and their long rifles and the stink of their damp uniforms?

‘And this pretty little kitten with the eyes that would kill me.’ The officer’s laugh held no humour. ‘Who is she?’

‘She’s my niece,’ Sergei said. He placed a protective arm round Anna’s shoulders. ‘She’s not important. She helps with our own baby, so that my wife can spend more time knitting scarves and gloves for our brave soldiers.’

The man walked over, placed his hands on his knees and lowered his face until it was at the same level as Anna’s. He inspected her closely.

‘So. Shall I take you down for interrogation as well?’

Anna gave a faint nod.

He smiled a snake’s smile, and she spat at him. Her spittle hit his cheek and slithered down. Without a thought, his gloved hand slapped her face, bouncing her head off the wall. She didn’t cry, but Maria did.

‘The child didn’t mean it,’ Maria called out. ‘She’s upset and frightened. Apologise immediately, Anna.’

Anna glared at the man. She wanted him to take her wherever Maria was going, so she started gathering more spittle in her mouth.

‘Anna!’ Maria begged.

‘I’m sorry,’ Anna whispered.

Abruptly he lost interest. ‘Come,’ he said. Suddenly they were gone and only the smell of them remained.

Five days. Anna counted the breaths.

Twenty-five breaths in a minute. Fifteen hundred breaths an hour. Thirty-six thousand breaths in a day and night.

She wasn’t so sure about the nights. When you sleep you breathe more slowly. But alone in the bed she didn’t sleep and when she did close her eyes on the sofa during the day, she woke up with nightmares. Irina scolded her for disturbing Sasha with her screams.

Five days. One hundred and forty-four thousand breaths.

On the sixth day Maria came home.

She said little and didn’t go to work. She lay on her side on the bed hour after hour, eyes wide open. Anna sat on the floor beside the cot and twisted her fingers into the quilt because it was the nearest she could get to Maria without touching her. And she knew that if she touched the fragile figure, Maria would break.

So she sat still, made no noise, just fed tiny cubes of pickled beetroot into Maria’s mouth. They turned Anna’s fingers and Maria’s lips the colour of cranberry juice.

When eventually Maria did emerge, her hair was styled differently. Even so, it didn’t quite hide the ugly marks on the side of her neck.

‘What are they?’ Anna whispered.

‘Cigarette burns.’

‘Was it an accident?’

‘Yes,’ Maria said quietly. ‘An accident of beliefs.’

Anna didn’t understand, but she knew she wasn’t meant to.

‘You have to go.’

Anna couldn’t believe the words.

‘You have to go, Annochka. Today.’

‘No.’

‘Don’t argue. You have to go.’

Maria was holding a small hessian bag in her hand and Anna knew it contained her own few belongings.

‘No, Maria, please no. I love you.’

That was when tears started to slide down Maria’s face and the bag shook in her hand.

‘It’s time for you to go, my love,’ Maria insisted. ‘Please don’t look so terrified. Sergei is going to take you to the station and then a good kind woman will travel with you all the way to Kazan.’

Anna wrapped her arms round Maria’s neck. ‘Come with me,’ she whispered.

Maria rocked her. ‘I can’t, little one. I’ve told you, the men who came here to the apartment want to ask me more questions. ’

‘Why?’

‘Because they want to know where Vasily is. He killed one of their own when they shot his parents and they don’t forgive that. They questioned me about where he could be hiding and I told them I know nothing but they… didn’t believe me. So they want to ask me more. It’s all right, don’t tremble so, I’ll be fine.’

‘No accidents?’

‘No, no more accidents.’ But Maria couldn’t stop a shiver. ‘Even though your papa is dead they have declared him an Enemy of the People and that means that you are in danger. You must leave. I’ll come for you as soon as I can.’

‘You promise?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ll write to you, so-’

‘No, Anna, it’s too dangerous. In six months, when all this blood-letting is over we’ll be together again. You’ll be staying with a distant cousin of mine but eventually I’ll come and care for you, like I promised your dear papa. I love you, my sweet one, and now we both have to be strong.’ Gently but firmly she detached Anna from her neck. ‘Now give me a smile.’

Anna smiled and felt her face crack into a thousand splinters.

33

The train jolted to a halt. Mikhail reached across and pulled the leather strap, so that the window slid all the way down. Sluggish air drifted into the carriage from outside, hot and heavy and laden with smuts from the engine. On the platform vendors fought to peddle baskets of food.

‘This compartment is like a bloody oven,’ complained the man in the seat on Mikhail’s right. It was his chief foreman from the factory, Lev Boriskin, a stocky man but powerfully built, with thick grey hair and a habit of fingering his lower lip.

‘I’ll see if there are any rain clouds ahead,’ Mikhail said.

He leaned again towards the window because it meant he would brush against Sofia. She was seated in the corner next to the window, her blonde head turned away from him, looking out at the crush of bodies on the platform. All day she had spoken very little, but could he blame her? From the start things had gone wrong. They had travelled into Dagorsk in a cart with four others, including a married couple who quarrelled at full volume all the way to the station. Then on the platform he had introduced her to Boriskin and to Alanya Sirova, Boriskin’s secretary, a woman of about thirty with ambitious eyes behind thick tortoiseshell spectacles. It was only when he saw Sofia’s face grow rigid with dismay and her gaze turn to him questioningly that he realised he’d forgotten to mention their travelling companions. He’d ushered her into the seat by the window.

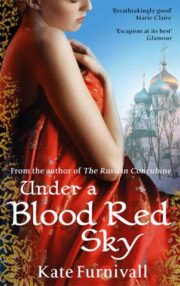

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.