‘Anna! Are you all right?’

The question came from Sofia. Anna smiled at her and nodded. They were packed together with eighteen others, all sitting on the floor of the truck, their bodies keeping each other warm. Everyone was so relieved not to be making the two-hour trek on foot along snow-covered trails to the usual Work Zone that there was a sense of delight in the small work gang. It briefly eased the permanent lines of tension across the women’s foreheads and the tightness around their mouths. Roll-call in camp had been fast and efficient for once, then a truck had backed up into the compound and dropped its tailgate. A group of twenty prisoners was selected at random to climb into the back. Puffing smoke from its exhaust pipe like a bad-tempered old man, the truck rolled through the double set of gates and out into the forest.

‘Where are we going?’ asked a small Tartar woman with a heavy accent.

‘Who cares? Wherever it is, this beats walking,’ someone responded.

‘I think they’re going to shoot us and dump our bodies in the forest.’

It was a young girl who spoke. On her first day as a teacher in Novgorod she was denounced by a pupil for mentioning she thought that, as an artistic form, the Romanov symbol of the double-headed eagle was more attractive than the stark hammer and sickle. Now an inmate of Davinsky Camp, every day she voiced the same fear. Shot and dumped. Anna felt sorry for her.

‘No, it’s obvious,’ Sofia said. ‘They’re short of labour somewhere, so they’re trucking us in to do some dirty job, I expect.’

But no one seemed to worry about what lay ahead. There was really no point, so they all chose to enjoy this moment. There was even raucous laughter when Nina suggested they were being taken to set up a publichniy dom, a brothel in one of the men’s camps.

‘I used to have beautiful tits,’ Tasha grinned. ‘Great big fleshy melons you could stand a teacup on. I’d have been the star of any brothel.’ She patted her flat chest. ‘Thin as a stick I am now, just look at me. They’re nothing but scrawny pancakes but I could still give any man his money’s worth.’ She rippled her body in a parody of seduction and everyone laughed.

‘Are you all right, Anna?’

It was Sofia again.

‘I’m fine. I’m watching the birds, a flock of them over there above the trees. See how they swoop and swirl. Don’t you wish you were a bird?’

Sofia’s hand rested for a moment on Anna’s forehead. ‘Try to sleep,’ she said gently.

‘No,’ Anna smiled. ‘I’m content to watch the birds.’

The truck’s engine growled its way across the flat marshy wasteland and jolted them over the slippery ice. Anna squinted at the flock in the distance. It occurred to her that they were moving strangely.

‘Are they crows?’ she asked.

‘Anna,’ Sofia whispered in her ear, ‘it’s smoke.’

Anna smiled. ‘I know it’s smoke. I was teasing you.’

Sofia laughed oddly. ‘Of course you were.’

The work was quite bearable. For one thing it was indoors inside a long well-lit shed, so the usual north wind that greeted their arrival in a desolate and ravaged landscape was not the problem. Anna tried not to breathe too deeply but the dust and the grit in the air made her cough worse, and she had to wrap the scarf tightly round her mouth.

‘It looks like we’ve come to party in hell,’ she muttered as they clambered from the truck.

‘No talking!’ the guard shouted.

‘It’s a fucking gold mine,’ Tasha said under her breath and made a furtive sign of the cross in front of her.

Ugly black craters stretched out before their eyes as though some alien monster had bitten vast chunks out of the land and stripped it of all vegetation. It was how Anna imagined the moon to be, but here, unlike on the moon, ants scurried all over the craters. Except they weren’t ants, they were men. Working at depths of thirty or forty metres, with barrows and pickaxes and shovels, and raising the rocks out of the huge craters via an intricate network of planks that looked like a spider’s web. The never-ending ear-splitting sound of hammering, and the speed with which the men raced up precipitous planks behind their over-laden barrows to fulfil their brigade’s norms, set Anna’s head spinning. It made road building look like child’s play.

‘In there. Davay, davay! Let’s go!’ the guard shouted, aiming the women in the direction of the wooden shed.

The work was simple, sorting rocks. At one end of the long shed was a large metal drum that tumbled the rocks from the barrows down a chute and on to a conveyor belt. It rattled noisily the thirty-metre length to the other end. The women had to sort the rocks, either to be hammered into smaller sizes or to be crushed under a giant steam hammer that ripped through the eardrums like a blowtorch. The air was so thick with rock dust that it was impossible to see clearly across to the thin line of windows on the far wall. Anna could feel the pain in her chest worsen as she worked. Her head throbbed in time to the steam hammer.

Somebody was laughing. She could hear them, but for some reason she couldn’t see them. The rocks on the conveyor belt started to retreat inside grey shadows that looked like ash tipped into the air, and she began to wonder if the problem was in her eyes rather than in the shed. She hesitated, then slowly raised her hand in front of her face. She saw nothing but ash.

‘Back to work, bistro!’ yelled a guard.

Her lungs were shutting down, she could feel it happening, starving her brain of oxygen. She dragged at the air in a last desperate gasp but it was far too late. She felt herself fall.

‘She needs injections of calcium chlorate. That’s what they’d use to cure her.’

‘Anna, talk to me.’

Anna could hear Sofia’s voice. It drifted softly down to her where she lay flat on her back, though for the moment she had no idea where that was.

‘Come on, Anna. You’re scaring me.’

With an effort of will that left her quivering, Anna clambered up from the dark towards the voice, but instantly regretted it when the raw agony in her lungs returned. The jolting under her body told her exactly where she was: back in the truck. She thought about opening her eyes but they had lead weights on them, so she gave up. Still voices curled around her.

‘She’s too sick to work any more.’

‘Keep your voice down. If the guards hear, they’ll just dump her over the side of the truck to freeze to death.’

‘What she needs is proper treatment.’

‘And proper food.’

A harsh laugh. ‘Don’t we all?’

Sofia’s voice again, warm on Anna’s skin. ‘Wake up, Anna. Bistro, quickly, you lazy toad. I’m not fooled, you know. I can tell you’re… just pretending.’

Anna forced her eyes open. The world jumped sharply into focus and she could smell the mouldy odour of damp earth as it emerged from its winter freeze in the forest. She was lying flat on her back, the sky black and sequinned above her, while much closer Sofia’s face swayed into view.

‘So you’ve bothered to wake up at last. How are you feeling?’

‘I’m fine.’

‘I know you are.’ Sofia’s voice was bright and cheerful. ‘So stop pretending.’

Anna laughed.

‘I’ve decided,’ Sofia announced. ‘I’m leaving.’

‘What?’

‘Leaving.’

‘Leaving where?’

‘Leaving Davinsky Camp. I’ve had enough of it, so I’m going to escape.’

‘No!’ Anna cried, then looked quickly about her and lowered her voice to a small whisper. ‘You’re insane, you mustn’t even try. Nearly everyone who tries it ends up dead. They’ll set the dogs on your trail and when they catch you they’ll put you in the isolator and we both know that’s worse than any coffin. You’ll die slowly in there.’

‘No I won’t, because I won’t let the bastards catch me.’

‘That’s what everyone says.’

‘But I mean it.’

‘So did they, and they’re dead. But if you’re so hell-bent on going, I’m coming too.’

Anna couldn’t believe she’d said the words to Sofia. She must be out of her mind. Her presence on the escape attempt would be a death sentence for both of them, but she was in such despair over what Sofia was planning that she just wasn’t thinking straight.

‘I’m coming too,’ she insisted. She was leaning against a tree trunk, pretending she didn’t really need it to hold her upright.

‘No, you’re not,’ Sofia said calmly. ‘You wouldn’t get ten miles with your lungs, never mind a thousand. Don’t look at me like that, you know it’s true.’

‘Everyone says that if you try to escape through the taiga, you must take someone with you, someone you can kill for food when there’s nothing but starvation left. So take me. I know I’m ill, so I won’t mind. You can eat me.’

Sofia hit her. She swung back her arm and gave Anna a hard slap that left a mark on the cheek. ‘Don’t you ever say that to me again.’

So Anna hugged her. Held her tight.

Anna was terrified. Terrified of losing Sofia. Terrified that Sofia would die out there. Terrified she would be caught and brought back and shut in the isolator until she either dropped dead or went insane.

‘Please, Sofia, stay. It doesn’t make sense. Why leave now? You’ve done five years already, so it’s only another five and you’ll be released.’

Only another five. Who was she fooling?

She’d tried tears and she’d tried begging. But nothing worked. Sofia was determined and couldn’t be stopped. For Anna it felt as though her heart was being cut out. Of course she couldn’t blame her friend for choosing to make a break for freedom, to find a life worth living. No one could deny her that. Thousands tried escape every year though very few actually made it to safety, but… it still felt like… No. Nyet. Anna wouldn’t think it, refused to let the word into her head. But at night when she lay awake racked by coughs and by fears for Sofia’s survival, the word slithered in, dark and silent as a snake. Desertion. It felt like desertion, like being abandoned yet again. No one Anna loved ever stayed.

Anna started counting. She counted the planks of wood in the wall and the nails in each plank and which type of nail, flat-headed or round-headed. It meant she didn’t have to think.

‘Stop it,’ Sofia snapped at her.

‘Stop what?’

‘Counting.’

‘What makes you think I’m counting?’

‘Because you’re sitting there staring with blank eyes at the opposite wall and I know you’re counting. Stop it, I hate it.’

‘I’m not counting.’

‘You are. Your lips are moving.’

‘I’m praying for you.’

‘Don’t lie.’

‘I’ll count if I want. Like you’ll escape if you want.’

They stared at each other, then looked away and said no more.

They planned it carefully. Sofia would follow the railway track, travel by night and hide up in the forest by day. It was safer that way and meant she wouldn’t suffer from the cold overnight because she’d be walking. It was March now and the temperatures were rising each day, the snow and ice melting, the floor of the pine forests turning into a soft damp carpet of needles. She should travel fast.

‘You must head for the River Ob,’ Anna urged her, ‘and once you’ve found it, follow it south. But even on foot and in the dark, travelling will be hard without identity papers.’

‘I’ll manage.’

Anna said nothing more. The likelihood of Sofia getting even as far as the River Ob was almost nil. Nevertheless they continued with their preparations and took to stealing, not only from the guards but also from other prisoners. They stole matches and string and pins for fish-hooks and a pair of extra leggings. They wanted to snatch a knife from the kitchens but nothing went right despite several attempts, and by the eve of the day planned for the escape, they still had no blade for Sofia. But Anna made one last foray.

‘Look,’ she said as she came into the barrack hut, her scarf wound tight over her chin.

She hunched down beside Sofia in their usual place on the wooden floor, backs to the wall near the door where the air was cleaner, to avoid the kerosene fumes that always set off Anna’s coughing spasms. From under a protective fold of her jacket she drew her final haul: a sharp-edged skinning knife, a small tin of tushonka, stewed beef, two thick slices of black bread and a pair of half decent canvas gloves.

Sofia’s eyes widened.

‘I stole them,’ Anna said. ‘Don’t worry, I paid nothing for them.’

They both knew what she meant.

‘Anna, you shouldn’t have. If a guard had caught you, you’d be shot and I don’t want you dead.’

‘I don’t want you dead either.’

Both spoke coolly, an edge to their voices. That’s how it was between them now, cool and practical. Sofia took the items from Anna’s cold hands and tucked them away in the secret pocket they had stitched inside her padded jacket.

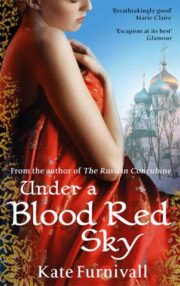

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.