Oddly, she didn’t feel sick with disappointment at her failure, even though she knew she had let both Anna and herself down badly. It was as if she was certain in that strange clear space inside her head that her brush with freedom was not yet over. So when the actual moment came, she was expecting it and didn’t hesitate.

The sky was beginning to darken and the rustlings on the forest floor were growing louder, when the girl suddenly pulled down her knickers, straddled the new latrine pit they’d dug and promptly christened it. The guard’s grin widened and he ambled over to watch the steam rise from the yellow trickle between her legs.

That was the moment. Sofia knew it as clearly as she knew her own name. She stepped up behind him in the gloom, raised her spade and slammed its metal blade on to the back of his head.

There was no going back now.

With a muffled grunt, he folded neatly to the ground and slumped with his head and one arm hanging down into the pit. She didn’t wait to find out if he was alive or dead. Before the girl had pulled up her knickers and screamed out in alarm, Sofia was gone.

They came after her with dogs, of course. She knew they would. So she’d stuck to the marshes where, at this time of year, the land was water-logged and it was harder for the hounds to track down her scent. She raced through the boggy wastes with long bounding strides, water spraying out behind her, heart pounding and skin prickling with fear.

Time and again she heard the dogs come close and threw herself down on her back in the stagnant water, her eyes closed tight, only her nose and mouth above the surface. She lay immobile like that for hours in the slime while the guards searched, telling herself it was better to be eaten alive by biting insects than by dogs.

At first she had the stash of food scraps in the secret pockets that Anna had sewn inside her jacket, but they didn’t last long. After that she’d existed on worms and tree bark and thin air. Once she was lucky. She stumbled upon an emaciated moose dying from a broken jaw. She’d used her knife to finish off the poor creature and, for two whole days, she’d remained beside the carcass filling her belly with meat, until a wolf drove her to abandon it.

As she travelled further through the taiga, mile after mile over brittle brown pine needles, seeking out the railway track that would lead her south, at times the loneliness was so bad that she shouted out at the top of her lungs, great whooping yells of sound, just to hear a human voice in the vast wilderness of pine trees. Nothing much lived there, barely any animals other than the occasional lumbering moose or solitary wolf, because there was almost nothing for them to eat. But in some odd kind of way the yelling and the shouting just made her feel worse: the silence that responded only left a hole in the world that she couldn’t fill.

Eventually she found the railway track that she and Anna had talked about, its silver lines snaking into the distance. She followed it day and night, even sleeping beside it because she was afraid of getting lost, till eventually she came to a river. Was this the Ob? How was she to know? She knew the River Ob headed south towards the Ural Mountains but was this it? She felt a wave of panic. She was weak with hunger and couldn’t think straight. The grey coils of water below her appeared horribly inviting.

She lost track of time. How long had she been wandering out here in this godforsaken wilderness? With an effort of will she forced her mind to focus and worked out that weeks must have passed, because the sun was higher in the sky now than when she had set out. As she tugged out her precious bent pin and twine that was wrapped in her pocket and started to trawl clumsily through the water, it occurred to her that the shoots on the birch trees had grown into full-size leaves and the warmth of the sun on her back made her skin come alive.

The first time she came across habitation she almost wept with pleasure. It was a farm, a scrawny subsistence scrap of worthless land, and she crouched behind a birch trunk all day, observing the comings and goings of the peasant couple who worked the place. An emaciated black and white cow was tethered to a fence next to a shed and she watched with savage envy as the farmer’s wife coaxed milk from the animal.

Could she go over there and beg a bowlful?

She stood up and took one step forward.

Her mouth filled with saliva and she felt her whole body ache with desire for it. Not just her stomach but the marrow in her bones and the few red cells left in her blood – even the small sacs inside her lungs. They all whimpered for one mouthful of that white liquid.

But to come so far and now risk everything?

She forced herself to sit again. To wait until dark. There was no moon, no stars, just another chill damp night inhabited only by bats, but Sofia was well used to it and moved easily through the darkness to the barn where the cow had been tucked away at the end of the day. She opened the lichen-covered door a crack and listened carefully. No sound, except the soft moist snoring of the cow. She slipped through the crack and felt a shiver of delight at being inside somewhere warm and protective at last, after so long outside facing the elements. Even the old cow was obliging, despite Sofia’s cold fingers, and allowed a few squirts of milk directly into her mouth. Never in her life had anything tasted so exquisite. That was when she made her mistake. The warmth, the smell of straw, the remnants of milk on her tongue, the sweet odour of the cow’s hide, it all melted the shield of ice she’d built around herself. Without stopping to think, she bundled the straw into a cosy nest, curled up in it and was instantly asleep. The night enveloped the barn.

Something sharp in her ribs woke her. She opened her eyes. It was a finger, thick-knuckled and full of strength. Attached to it was a hand, the skin stretched over a spider’s web of blue veins. Sofia leapt to her feet.

The farmer’s wife was just visible, standing in front of her in the first wisps of early morning light. The woman said nothing but pressed a cloth bundle into Sofia’s hands. She quickly led the cow out of the barn, but not before giving Sofia a sharp shake of her grey head in warning. Outside, her husband could be heard whistling and stacking logs on to a cart.

The barn door shut.

‘Spasibo,’ Sofia whispered into the emptiness.

She longed to call the woman back and wrap her arms around her. Instead she ate the food in the bundle, kept an eye to a knot-hole in the door and, when the farmer had finished with his logs, she vanished back into the lonely forest.

After that, things went wrong. Badly wrong. It was her own fault. She almost drowned when she was stupid enough to take a short cut by swimming across a tributary of the river where the currents were lethal, and five times she came close to being caught with her hand in a chicken coop or stealing from a washing line. She lived on her wits, but as the villages started to appear with more regularity, it grew too dangerous to move by day without identity papers, so she travelled only at night. It slowed her progress.

Then disaster. For one whole insane week she headed in the wrong direction under starless skies, not realising the Ob had swung west.

‘Dura! Stupid fool!’

She cursed her idiocy and slumped down in a slice of moonlight on the river bank, her blistered feet dangling in the dark waters. Closing her eyes, she forced her mind to picture the place she was aiming for. Tivil, it was called. She’d never been there, but she conjured up a picture of it with ease. It was no more than a small distant speck in a vast land, a sleepy village somewhere in a fold of the ancient Ural Mountains.

‘Oh Anna, how the hell am I going to find it?’

Yet now, at last, she was here. In the clearing among the silver birches, the mossy cabin with its crooked roof warm at her back, the last of the sun’s rays on her face. Here, right in the heart of the Ural Mountains. But it seemed that just when she’d reached her goal, they were coming for her again. The hound was so close she could hear its whines.

She darted back into the cabin, snatched up her knife and ran.

Seconds later two men with rifles and a dog burst out of the tree line, but by then she had already put the hut between them and herself as she raced for the back of the clearing, hunched low, breathing hard. The dark trunks opened up and she fell into their cool protection. That was when she saw the boy. And in a hollow not three paces away from him crouched a wolf.

6

Pyotr Pashin felt his heart curl up in his chest. He didn’t move a muscle, not even to blink, just stared at the creature. Its mean yellow eyes were fixed on him and he didn’t dare breathe. Never before in his young life had he stood so close to a wolf.

Dead ones, yes, he’d seen plenty of those outside Boris’s izba down in the village where their pelts were hung out on drying racks. Pyotr and his friend Yuri liked to trail the backs of their hands through the dense silky fur and even stuff a finger between the razor-edged teeth if they dared, but this was different. This wolf ’s black lips were pulled back in a silent snarl. The last thing in the whole world that Pyotr wanted to do now was stick a finger in its mouth.

He’d jumped at the chance to come hunting when Boris asked him.

‘You’re a skinny runt,’ Boris had pointed out. ‘But you’re good with the hound.’

Which meant he wanted Pyotr to do all the running. But it hadn’t turned out to be a good day. Game was scarce and his other hunting companion, Igor, was tight-lipped as a lizard, so Boris had started in on the flask in his pocket which only sent the day tumbling from bad to worse. It ended up with Boris giving Pyotr a clout with his rifle for not keeping a tight enough hold on the leash, which made Pyotr scoot off among the trees in a sulk.

‘Pyotr! Come back here, you skinny little bastard,’ Boris yelled into the twilit world of forest shadows, ‘or I’ll skin the hide off you!’

Pyotr ignored him. He knew that what he was doing was wrong – it broke the first rule of forest lore, which is that you must never lose contact with your companions. Children of the raion grew up bombarded with bedtime stories of how you must never, never roam alone in the forest, a place where you will be instantly devoured by goblins or wolves or even a fierce-eyed axeman who eats children for breakfast. The forest has a huge and hungry mouth of its own, they were told, and it will swallow you without a trace if you give it even half a chance.

But Pyotr was eleven now and he reckoned he was able to look out for himself, and anyway, he was angry at Boris for the clout with the rifle butt. Also, though he wasn’t sure exactly why and he felt stupid even thinking this, in this part of the forest the air was different. It seemed to lick his cheek as daylight began to fade. Somehow, it drew him to this quiet circle of light that was the small clearing in the trees.

He caught sight of the back of the cabin, covered in bright green moss, and the fallen mess of branches sprawled lazily in the sun on the soft earth. His interest was roused. He took one more step and immediately heard a low-throated sound at his feet that made the hairs rise on the back of his neck. He swung round, and that was when he saw the wolf and his heart folded in his chest.

He didn’t dare breathe. Slowly, so slowly he wasn’t sure it was happening at all, he started to move his left hand towards the whistle that hung on a green cord round his neck.

Then, abruptly, a blur of moonlight-pale hair and long golden limbs hurtled into the stillness. A young woman was churning up the air around him, her breath so loud he wanted to shout at her, to warn her, but he could feel a wild pulse thudding in his throat that prevented it. She stopped, blue eyes wide with surprise, but instead of screaming at the sight of the wolf, she gave it no more than a quick glance. Instead she smiled at Pyotr. It was a slow, slanting smile, small at first, then broadening into a wide conspiratorial grin.

‘Hello,’ she mouthed. ‘Privet.’

She raised a finger to her lips and held it there as a signal to him to stay quiet, her mouth twitching as if in fun, but when he looked into her eyes, they weren’t laughing. There was something in them that Pyotr recognised. A quivering. A sort of drawing down deep into herself, the same as he’d seen in the eyes of one of the boys at school when the bigger boys started picking on him. She was scared.

At that moment it dawned on Pyotr what she was. She was a fugitive. An Enemy of the State on the run. They’d been warned about them in the weekly meetings in the hall. A sudden confusion tightened his chest. No normal person behaved so oddly – did they? So he made his decision. He raised the whistle to his mouth. Later he would recall the feel of the cold hard metal on his lips and remember the hammering in his heart as the two of them stood, saying nothing, in front of those mean yellow eyes in the shade of the big pine.

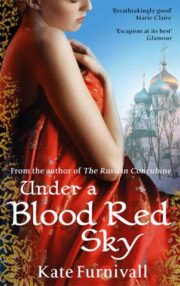

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.